Things to Come

Curator: Doreet LeVitte Harten, co-curator: Avshalom Suliman

14/04/2016 -

20/08/2016

Science fiction is a relativey new field that deals with the impact of imagined science and technology upon society and individuals. It is a controlled way to think and dream about the future, which at the same time reflects the values of the culture in which it is produced. It is through science fiction that existing social desires, cultural aspirations, and political and technological patterns manifest themselves. The imagined vision of the future speaks volumes about the present, and is always also anchored in the past.

The show aims to define the speculative fiction in its visual modus and to point towards its historical context. It brings together and conflates different parameters without differentiating between so called high art and popular expression. In a way, science fiction can be defined as the modern imagination and the works of the artists presented here testify to this fact.

What fuses art with science fiction is the ability to look at things unseen. In the sense that a good portrait, for example, is not a mirror image of a given person but a quest of deciphering, evoking a certain truth which is then shared by the artist and the observer. While art’s journey is perceived as a vertical dive into a truth that lies beneath the surface, it is the surface itself that science fiction uses as the plateaux of its discoveries. At the center of that rhizomatic plain stand the permutations, variations, and mutations, or in short – the state of things to come.

I do not make any sketches before I create my objects. I am inspired by basic materials I find on flea markets or in my workshop. I like using materials that have a history behind them and can tell a story through their patina, the scratches and dust they gather. I like the way old leather and wood smell and the feel of brass and copper.

I want to give a new life and function to old, discarded objects, and to build a bridge between the aesthetics and the atmosphere of the 19th century, fin-de-siècle era and the high-tech surrounding us today. Jules Verne, Tim Burton, Mad Max, mystery and fairy tales, as well as the worlds of science fiction authors such as H.G. Wells, are some of the building blocks of these bridges. I want to create things that seem to be part of a world that could possibly exist, but in fact does not. Sometimes I want my objects to bring a smile to the face of a visitor to my studio while he touches them. I want to reactivate the fantasy in the minds of people.

http://steampunker.de/en/home/#.Vro2Sfl97IU

The foundation of my work is music. For the past ten years I have been creating and performing with indie-rock bands (Lebanon, Suicidal Furniture), and music plays an important part in my artistic practice. I try to infuse the energies of music into imagery that draws on pagan tribal cultures, on anxieties induced by horror movies, and on landscapes conjured by literary works of science fiction. The idea is to work with high, immediate, explosive, and aggressive intensity, whose structure and function emerge intuitively through the material and the exploration of the potential it holds. Similar to what happens in a musical piece.

I mostly work with things that I find in the streets, leftover materials, discarded and defective objects that have lost their place in the world. It is an attraction that reverberates my own identification with a sort of intimate belonging to this world. It is important for me to preserve the identity of the objects and materials, I want to revive them by embracing them, to charge them with a functionality expressive of an imaginary order, bogus even. I want to find a place for them and me in the world so that we may become real. My works revolve around the question: how does a fantasy create the reality we experience around us, and how does that reality collapses back into someone else’s fantasy? My works respond to contemporary materials, celebrate with it, and take part in the zeitgeist of these times in order to highlight the potential hidden in it, in order to stand on the threshold of that which is destined to come.

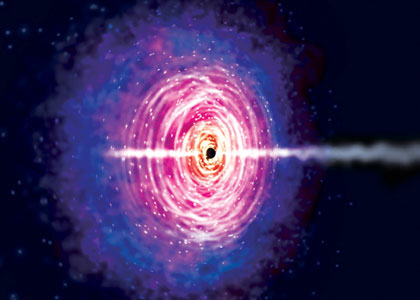

In collaboration with Sara Mast (installation), Jason Bolte (sound) and Nico Yunes (scientific data)

The data was provided by my scientific collaborator on this project, astrophysicist Nico Yunes.

The work was originally commissioned for a symposium celebrating Einstein’s phenomenal contribution to modern physics. Using custom software, I created an animated sequence depicting the surface and internal dynamics of a black hole. The dramatic spirals at the middle of the video illustrate the gravitational waves generated by “zoom-whirl” orbits of two black holes circling one another, an important phenomenon in the study of cosmology. As with much of my practice, Black Hole Simulation reflects my interest in the aesthetics of science, and how the knowledge it produces changes our understanding of the scale, time, and energy of our bodies.

I was six years old when I heard barking coming out of the radio. I remember coming close in an attempt to understand what’s coming out of it, and getting terribly scared. I think I understood eventually that it was a man’s voice and not a dog’s, but I told no-one about this. Years later I realized that it was Hitler in one of his many speeches, but by then the voice has already lodged itself inside me. About ten years ago it emerged, and I began vomiting it out. It was then that Vod Renro materialized, a persona I assume in the drawings and performances I create, a cross between my father, myself, and the image of Hitler. I 2006 I exhibited the show My Friend Hitler.

I always start with a 70X100 drawing. Anything can serve as a raw material in my mental blender: appropriated images of other artists’ works, comic-book superheroes and pop stars, the image of Hitler. I use an old Xerox machine to duplicate my drawing, which I then transfer to a new surface using thinner fluid. I work with whatever comes through using colorful felt-tip pens. At the end of this process I destroy the original, whose DNA has been duplicated into the series and distorted by the printing errors and my marks.

I recently started thinking about a series of paintings I began in 1989. Back then I was interested in a peculiar parasite that appeared on plants in my Kibbutz in the form of a thin yellow worm-like shape, and whose image entered my works. I suddenly recalled seeing a simulation of the Ebola virus in a TV report, years later: a thin worm-like thread that can reproduce itself remarkably well. In many of my works of the last few years this reproductive principle plays an active role, each time taking on a different face and a different voice.

The work was produced with the support of Hapais council for the culture and Arts

Art, to me, is a form of visual séance whose purpose is to summon and extricate latent forces, ones that are (often purposely) repressed by the official culture and regime. Art can produce new and powerful worlds, worlds with independent will for survival and a passion for existing not unlike that of organisms. It is not confined to the space of the “white cube” but rather is everywhere: in highways and interchanges, on the walls of houses, in commercial galleries, hospitals, or in outer space – but it always begins with the development of a new kind of sight. It is a way of seeing, the kind that reaches beyond the optic, psychological, or social prisms.

We no longer paint or sculpt with matter but in energies, with cultural raw materials, in personal and collective memories, and with the spirit. I like using the term “fusion” for describing the attitude with which I create. And just like in fusion cooking or fusion music, when it comes to the ingredients in the studio’s cauldron, no style or influence is off the table. Popular science, science fiction, or Japanese poetry, are materials like any other. Fusion is what melts these substances together till they reach a state where it is hard to make them apart. To me, the purpose of this melting down is not just a formal game with a potential of producing hybrid creatures, but also the release of subterranean forces and latent energies as a result of different materials activating each other, making one another disappear into a new state of being.

Throughout the 20th century science fiction was one of the forces that enabled the broadening of horizons onto new ways of seeing. I believe the artists of the new age, on the verge of which we stand in the last half-century, must also develop the ability to see beyond the screen of the dense cultural matrix that at times seems to be the only thing that is left, to be able to look as close – and as far – as possible.

Eli Gur Arie’s works are allegories for a world obsessed with smooth, shiny, and seductive surfaces. His basic materials – Styrofoam covered with fiberglass and polyester resin coated with auto paint – are anchored in a material, cultural sphere that is at once distinctly Israeli and altogether global. Their high finished surfaces place his works as products of a consumerist society in its terminal stages.

At the same time, they are an ensemble of scientific solutions meant to accommodate its almost-inevitable future. While using the very techniques that characterize a society in need of a constant visual enticement, the artist also criticizes these very methods, pointing us to outcomes of their usage. The main subject matter of his oeuvre is the horrific possibility of an apocalyptic event which shall emerge out of the systematic destruction of entire ecological systems by our industrialized society of Late Capitalism. His works may be seen as closed bio-mechanic systems that present us with an array of probabilities, mutations, and strategies meant for sustaining life in an

impossible environment, and as such – as a catalogue listing proposals for survival.

With: Ori Golad and Deborah Aroshas

Music: Hanan Revivo

Sound: Boaz Bachrach

Prod. assistant and art: Mayan Shay May-Raz

In an age when the lines between the real and the virtual are constantly fading away, do technological advancements necessarily indicate mankind’s progress? Sight is a short film that takes place in the near future, when smartphones have been replaced by smart contact lenses. This results in “augmented reality”, a reality that dissolves completely into the virtual. In the new world, digital apps run our schedule and games make our life more enjoyable and more productive. The video depicts a day in the life of a protagonist named Patrick, allowing us a critical, at times even grim, view into our society and where it seems to be heading.

www.robotgeniusfilms.com

Data analysis and visualization by Accurat (www.Accurat.it): Giorgia Lupi, Simone Quadri, Gabriele Rossi with Davide Ciuffi, Federica Fragapane, Stefania Guerra. The visualization was originally published in La Lettura (Corriere della Sera) in 2012. (אם רוצים לציין את הקרדיט לעיתון, אפשר להכניס כאן או בהערה למטה)

The Future, as Foretold in the Past is a data visualization of a timeline that explores future events as predicted by famous novels.

The visualization is built on a main horizontal axis depicting a distorted timeline of events appearing at regular intervals, starting our future-timeline in 2012. The y-axis is dedicated to the year the novel/book foretelling the event was published. We then wanted to add further layers of analysis to our piece, finding out main typologies of foretold events – which are mostly social, scientific, technological, and political. We have also depicted the genre of the books and, most importantly, divided them into positive, neutral, or negative events.

The good news is, in 802,701 the world will still exist!

The city hovers authoritatively overhead, a unique view of the colossus in which most of us live. It is an icon of today’s city in a regular turning rhythm, when every moment links a new event back onto itself. The rotating frequencies contain visual and symbolic rhythms of present-day cities, Shanghai and Prague being but two of its sources. An abstract story of a universal city culminates in several phases and then sinks back into darkness. It is as if a charge of energy left the space and then after a while returned for another hypnotic cycle.

The surface of the original relief projection was created as a circular construction made from the packages of real products manufactured in China. This bell-shaped hood can function as an art object in itself, as an illuminated physical casing. In this piece I wish to encourage people to confront the city as a whole and to take advantage of its potential (dual) energy, which unfortunately usually manifests itself negatively, for instance in its effect on a person’s psyche. Another aim is to find in oneself a positive approach to the city as an inevitable mechanism of today’s society.

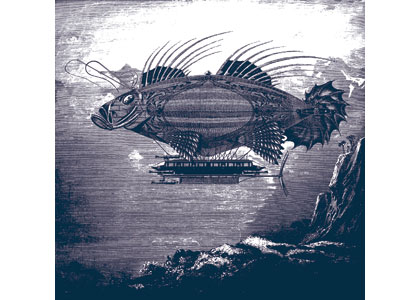

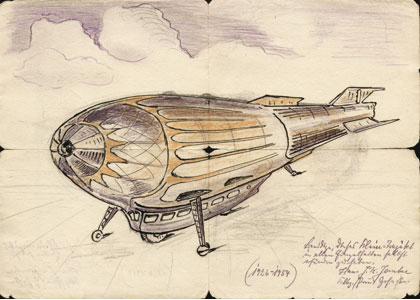

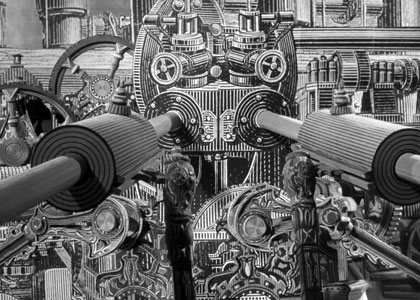

My piece is an illustration of an armed airship shaped like a fish I was commissioned to do in 2010. The work is digital but uses collaged engravings to imitate the art styles of the 19th century. One of the first artists to use 19th century engravings as source materials for his collages was Max Ernst, whose best known works in this technique are La femme 100 têtes (1929) and Une semaine de bonté (1934).

The technique has since been developed by many other artists, notably Wilfried Sätty (1939-1982), a German artist who lived in San Francisco during the 1960s and 70s. Sätty’s work maintained Ernst’s Surrealist approach but downplayed this aspect in the third book of his work, The Illustrated Edgar Allan Poe (1976). This book, and Sätty’s work in general, has influenced my own development of the use of engraving in collages. The attraction of the process for the creation of period illustrations is that of being able to use material from the period itself in order to create imagery that seems authentically of the time. Where Ernst and others have used collage for its disjunctive qualities, I attempt to create a coherent illustration.

www.johncoulthart.com

Like many of my generation I grew up reading the science fiction books that came out in Israel in the 1970s and 1980s. Visiting the public library I would gravitate away from the shelves where the “serious” literature was kept, pulled by invisible tractor beams. I would search for the cooler titles, the ones that could take me farther away: away from school and the kibbutz, away from an Israel of rising inflation-rates and wars. I was drawn to the colorful covers of Ram-Dor Books which looked like 1950s American pulp magazines, to the more reserved line of Masada’s sci-fi series, and the collagist covers of Sandhaus-Eisenstein studio for Am Oved publishing house. It is hard for me to say what, if anything, of all this is still an active agent in my paintings today. Nevertheless, the thing about science fiction is that it is not necessarily only a gaze towards a distant future, but also provides a certain perspective on the present. Maybe popcorn textured walls and spacecrafts, androids and nuclear ambiguity do, after all, still pulsate in my works.

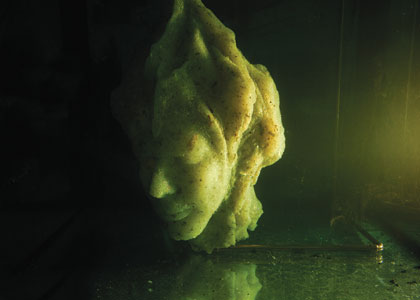

Time:17:45 to 17:46, Tuesday, December 29th, 2015.

Location: a studio in Panorama building, Ben Zvi Road, South Tel Aviv, The Dan Region, Israel, the Middle East, planet Earth….

In a split of a moment, the liquid silicone shell congeals, capturing the image of what is laid inside it, copying and preserving it; a single, specific moment in time. This is just one of countless moments on the space-time continuum, but it is the one that had been caught by the mother-mold and so will make it to the next level as something that will be remembered. A mountain grows on my head, its eyes shut. One moment’s thought preserved for all eternity.

This is how History works – without justice or logic. It is just the unfolding of events as they were preserved in human memory, written down, and gathered into something utterly simple as the following definition: that which happened. However, what if what we think we know about our history and prehistory is but the tip of the iceberg of the complete story, a story that may not even be “ours”?

What attracts me to questions like these is the fact we may probably never get a clear answer for them. Even within the scientific paradigm there is always the chance that everything we “know” today will be refuted tomorrow, or will be discovered to be a mere tiny fraction of complete reality. The perception of truth instructing our lives is a momentary fracture on the universe’s time-line, and may very well be the first chapter of a multi-volume saga.

Equipped with these thoughts I embark on the process of making what will eventually become If I Could, I Would….

My drawings play with mystical symbols to explore the collective unconscious and the irrational drive that spans centuries and lurks at the edges of human culture and civilization. Taking their inspiration from ancient cults, constructed myths, and historical monuments, they create a hybrid reality, focusing on the dark side of collective dreams and preferred versions of desired histories. I am interested in discussing the ways that myth, history, and fantasy intersect, how constructs of the imagination are projected onto nature, and how easily history can collapse into a fantasy. With that I wish to suggest a different approach to what we define and constitute as a civilized space.

The drawings featured in the exhibition offer a portrait of heroism that frames German cultural history with futuristic promise. Using found materials such as comics and sci-fi book covers, I appropriate the cultural symbolism of fantasy to reassemble visions of national identity. Historical monuments and artworks such as Bernhard Hoetger’s Niedersachsenstein and Ernst Barlach’s Hovering Angel unexpectedly inhabit sci-fi landscapes from classic cult films like Time Machine and Phase IV. By excavating strange moments in German history and mapping them back into a contemporary present, the works explore the idea of historical mistranslation and present a meditation on irrationality and nationalism.

Karl Hans Joachim Janke (1909‒1988) was a German artist and inventor. A prolific futurist, Janke created numerous models and drawings, mainly for aerospace engineering – all of which were executed during his stay at Hubertusburg Hospital in Wermsdorf, and later at the psychiatric hospital Arnsdorf, where he spent his last forty years. Janke was diagnosed with a chronic paranoid schizophrenia, which is characterized by an inventor-delusion. More than 2500 drawings document his inventions, including atomic propulsion models, domestic lamps that collect steric energy, and spaceships that fly without any need for energy. Janke built many models for his flight vehicles, futuristic spaceships, and electromechanical devices, designed a “pedigree of mankind,”wrote political and military strategies, and left extensive correspondence. He also devised proposals for peaceful uses of nuclear energy and for new energy sources, based on the use of the earth’s magnetic field. Janke did not perceive himself as an artist, but as a scientist. Indeed, his sketches, however imaginative and visionary, were so authoritative in their precision that it was difficult to dismiss them as mere products of his imagination. In a testament before his death Janke wrote “I kindly ask that the pictures and albums be kept safe, along with the many drawings and models that I created for mankind.”

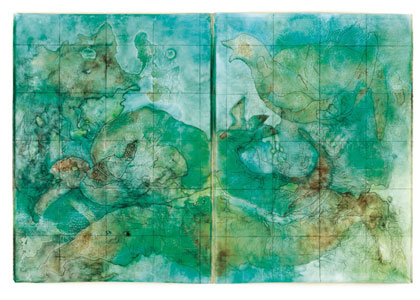

The Greek philosopher Thales identified the source of all things and their essence to be one with water. Thales, who delved into astronomy, geometry and cosmology, searched for a law of nature that would explain all phenomena by the power of a consistent and intrinsic principle rather than reliance on past events, that is, independently of history. His assertion that “all is water” refers to the one quality common to all occurrences: their constant flux.

All is Water is one unit from a cycle of seven spreads in my Atlas project, created over the course of several years in which I lived in an abandoned house on 17A Brenner St., Tel Aviv, destined for demolition. The “cut” or separation line in each pair of canvases marks the form of an open book whose pages were separated and hung next to one another, and also crosses the form/image, dissecting it. The wide, split, sheets turn out to be parts of a dismembered whole, like the pages of an unbound book. Working on the Atlas cycle was like travelling through time. I worked as if a model of the entire universe was spread on a local, unstable foundation, concealed in the heart of our urban life. The physical features of the place, its walls in particular, served as the work’s substantial material support, a dynamic platform on which I drew the marks of a journey to far-off realms in the past and the future.

I always take photos for my paintings, and in a way the camera is my sketchbook. Some images convey my fascination with layering and weaving together spaces. Foreground and background merge and shift positions, creating visual unease and tension. Other images are taken in places that are specific and non-specific imultaneously. I am interested in exactly these kinds of places, which I use as the ground for my paintings, shaping them in many directions.

The title of the painting Between reflects my interest in creating a space that has an ambiguous quality. One can either be in the shelter of the enclosed space looking out at the strangely artificial bright lights, or be standing on the outside looking in. Both ways to read this image work equally well.

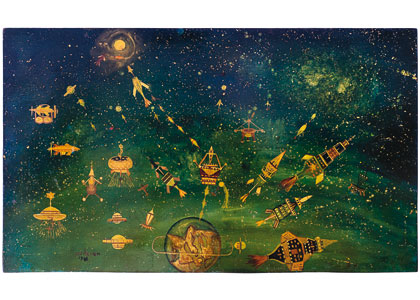

Moshe Elnatan’s paintings are crowded with events of cosmic proportions and with biblical scenes, with the portraits of famous leaders from Ben Gurion to Joseph Stalin alongside occult symbols, with sputniks, rockets, spaceships, and planets – as well as with spectacular floral bouquets. The mythic and the futuristic, mundane and awe-inspiring, human and cosmic are portrayed with an intensity characteristic to many artists who worked outside of the canon and the established art community. Known in the Jerusalem scene mostly as the “Falafel King,” after the small restaurant that was his livelihood, Elnatan was often labeled a ‘naïve artist.’ A profound examination of his artistic estate reveals a man who lived an intense life before he began painting, and a creator whose sensitive awareness was attuned to the latest technological and political developments of his time.

We would build an armor; its qualities shall provide what’s needed

in order to stay a mere potential being; its color, indefinite, will change constantly, entirely dependent on its surroundings (the angle of light, the position of its observer); its form will be ripped open (a segment of a Torus), falling short of realizing all that is concealed within its geometric pattern. Its shape shall stand on the threshold between second and third dimensions (neither a slice nor an object), and will constitute a multi-dimensional potential. Its holographic coating (a material with encryption capabilities) will be a source of excessive information, spread on the entire gamut of every shade. It should be noted – the infinite number of shapes we could have collapsed into; existence takes place between the fragments of all things / (it should be kept in mind that) / towers are also pits.

Yuki Onna is the Ghost in the Machine is concerned with the potential embedded in a repressed memory or a dream which resurfaces into the conscious mind. Is it possible to perfectly retrieve a memory as it is done by digital memory-machines (computers)? When a memory resurfaces from our consciousness’ repressed area, the movement of its mechanism in itself produces a deviation, and the memory, dream, or some aspects of them, change. The remembering-apparatus is part of the memory, and the act of remembering in itself causes it to morph.

Yuki Onna (“The Snow Woman”) is a Japanese ghost story in a collection entitled Kwaidan (“Ghosts”). In a stormy night in the woods, Minokichi the lumberjack comes across the dreadful snow-woman who agrees to spare his life, on condition that he will never talk

about her. He keeps their secret until one night, years later, he suddenly remembers the incident and recounts the story to his wife.

The work is a machine that displays a play in three acts, each presented on a different stage, which unfolds the story of Yuki Onna. Both the different stages and what is presented on them are made from phosphorescent paper sensitive to light, so that they function as light-absorbing screens and at the same time as shadow-casting objects. The entire apparatus accumulates light and shadow when in its folded form and, when the play unfolds and becomes visible, shadows spread out as images drift away from their origins in a regular rhythmic cycle. The architecture, mechanics, and materials of this work produce countless points of deviation through which memory escapes, in the dead of the mind’s night.

Robert Martens’ YouTube video was put together as a homage to the great Karel Zeman (1910-1989) – a Czech film director, artist, production designer, and animator, best known for his feature films, in which he combined live-action with innovative animation techniques. Created between 1955 to 1970, most of these films were based on Jules Verne’s stories such as Journey to the Center of the Earth and The Mysterious Island. Zeman’s unique style has influenced directors like Terry Gilliam, Tim Burton, and Wes Anderson, who were inspired by his use of animation set against incredibly detailed hand-painted backgrounds.

Zeman helped fashion the aesthetics we now identify as Steampunk, combining alternative visionary technology set in a 19th century, pre-electric Victorian world. This was also typical of Verne’s own vision of a tech-future, illustrated in his books using traditional engravings. Robert Martens’ piece is an admirer’s homage, compiled of scenes taken from several films that Zeman directed throughout his career.

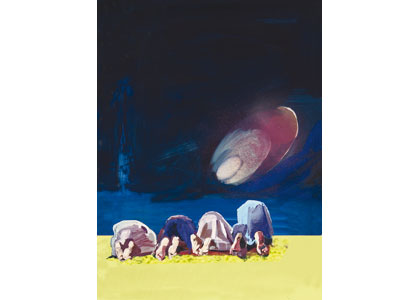

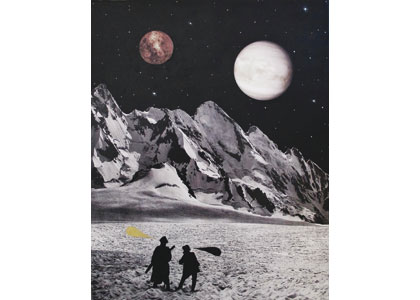

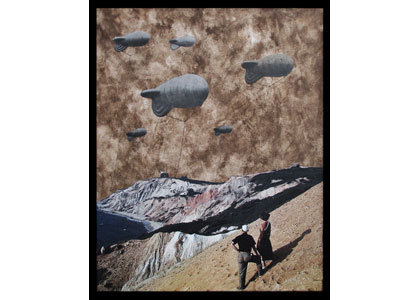

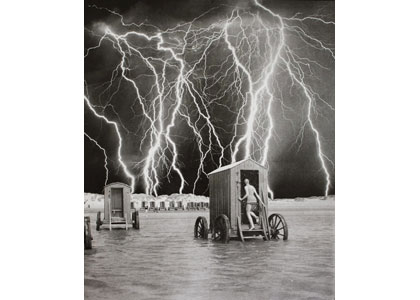

My works are characterized by an awareness of things to come, of looming catastrophes and events of an apocalyptic scope. They are immersed in that famous “sense of wonder” known to the adepts of the science fiction genre as a core experience. This sense of wonder may also be recognized as the presence of the sublime in secular times. The people in my collages are almost always observing some cosmic event of a “sublime” magnitude: planets and suns, structures and events are hovering above them, threatening to come crushing down on heads. I cultivate a discrepancy between the narratives, which operate on an immense scale, and the modest size of the works, in an attempt to avoid the temptation of a spectacle. This imbalance creates a sense of gravity, mirrored by the compositions in which the figures are depicted in the picture’s lowest level, often from the back, so viewers look at figures replicating their own act of looking.

I use an endless arsenal of images and, like a bricoleur, construct new visual sentences from “syllables” designed for entirely different contexts. It is a method of hybridization that initiates a third space where known truths begin to quiver, a space whose associative dynamics are unclear. I use this imbalanced state, reflected time and again in the compositions of the works, to reboot human imagination. It is an act much needed in times where the simple ability to imagine is being systematically annihilated through blinding spectacles.

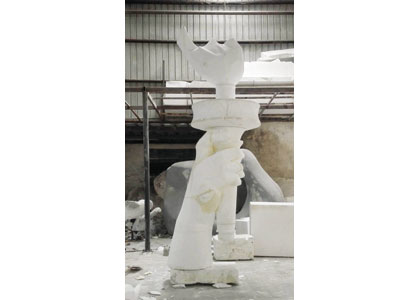

The raised hand of the Statue of Liberty has become an indispensable attribute in many science fiction movies. It can enter the frame during the outbreak of a natural catastrophe or alien invasion, the action taking place either inside the monument or on the surface of its giant hand, and sometimes it just pops out of the ground in a post-apocalyptic landscape. This image is close to my heart, and stands at the center of my visual research in the studio.

Much like ancient Roman statuary, the hand of the Statue of Liberty has nothing to do with any real artistic value or judgment. Its significance is closely linked with the deliberate transformation process that New York had gone through in popular media from a physical entity to a visual icon. In this context, the hand serves as a timeless symbol of an era and an ideology, the only stable object within an ever changing landscape. It creates a recognizable context, a background on which one can read the transformations of the film’s scenery, time, or action.

By placing Liberty Buried in the museum’s courtyard, I wanted to transform an entire urban setting into a frame out of a science-fiction film. I consider it a landscape piece that deals with the application of time on a place, with the diffusion between worlds, and with a scenery that gathers different realities set in different spatial locations into one vanishing point.

Director: Daniel Landau

Photography: Ben Hertzog

Still Phootography: Dima Valershtein

Editor: Ziv Appelberg

Art: Shay Govhary

Sound design: Daniel Meir

The astronaut, much like the artist, embarks on a voyage of historical significance that is also a journey to fulfill a personal dream. He will encounter many obstacles along the way to making his vision real, but passion, willpower and persistence will help him find a way to overcome them, if not in the most elegant way. In the process, he will learn that determination and perseverance can, indeed, make up for what he lacks in aptitude. His struggle to establish a Falafel stand on the moon will prove that a driven individual – even if his motivation is channeled to the pursuit of the most absurd mission – can make the entire world succumb to one’s vision. The desire to sound a unique voice, even at the cost of going against good reason and common sense, leads the astronaut on a seemingly pointless journey that nevertheless ends with an absurd victorious cry.

The structures are born out of a constant collection of materials and objects that I bring into the studio, inspect until I understand their nature, and then combine together, as part of my search for a vertical object of some sort. The results are, very often, totemic ‘poles’ whose sole purpose is to declare my joining of the age-old race after height and might, common to various civilizations from the dawn of history. This aspiration for the heights and the cult of the big and impressive is ingrained in our DNA. From the biblical Tower of Babel to New York’s skyscrapers, the history of architecture is fraught with ziggurats expressive of the human desire to connect with the power of the vertical. In recent years, I have been exploring the image of the tower vis-à-vis the structure of the rocket, and how architectural patterns and certain objects are influenced by the culture and technologies of the societies that conceive them. My sculptures point to this ongoing dialogue between structure and user, and between the concrete structure, its symbolic significance to the culture in which it exists, and its ritual characteristics.

Written and directed by Till Nowak

Director of photography: Ivan Robles Mendoza Starring: Leslie Barany

Visual effects and editing: Till Nowak

Sound: Andreas Radzuweit Sound FX

editing: Lukas Bonewitz Courtesy: Claus Friede*Contempora

Since the 1970s, scientists have been conducting experiments with bizarre amusement rides in order to study their effects on the human brain.

The fictional documentary The Centrifuge Brain Project is based on my childhood fascination for the strange atmosphere of amusement parks. I collected hand held camera footage and used digital animation to create a series of non-existing thrill rides. Appropriating the aesthetics of a television documentary, my short film takes a tongue-in-cheek look at mankind’s confused search for happiness and freedom, and at our sometimes misguided ways of achieving them.

The Walking City is a concept proposed by British architect Ron Herron in 1964. Herron was active in the avant-garde architects group Archigram, whose other prominent members included Peter Cook, Warren Chalk, Dennis Crompton, Michael Webb, and David Greene. He proposed building massive mobile robotic structures that would have their own intelligence, and could freely roam the world, moving to wherever their resources or manufacturing abilities were needed.

The walking city has become a reoccurring theme in science fiction literature, a topos signifying the endurance of man’s communal effort to maintain a society (albeit sometimes a dystopian one), in a radically morphing hostile world. Referencing the utopian visions of the Archigram group from the 1960s, Walking City is a slowly evolving video sculpture. The language of materials and patterns seen in radical architecture transform as the nomadic city walks endlessly, adapting to the environments it encounters. Universal Everything is a UK based studio collective and research practice, working in graphic design, digital installations, and large-scale event design.

Courtesy of Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam;

Sommer Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv; Petzel Gallery, New York; Capitain Petzel, Berlin

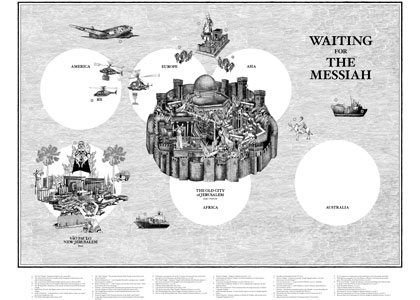

The map was created in the context of the film Inferno, 2013, with the support of the 31st Sדo Paulo Biennial, 2014

Illustrator: Batia Kolton, graphic design: Gila Kaplan and Oded Korach

Waiting for the Messiah was created in the context of my film Inferno (2013). The starting point of Inferno is the construction of the third Temple of Solomon (Templo de Salmão) in São Paulo by a Brazilian Neo-Pentecostal Church. Built to biblical specifications, this new temple is a replica of the first temple in Jerusalem, the violent destruction of which signaled the Diaspora of the Jewish people in the 6th century BCE. Inferno confronts this conflation of place, history, and belief, providing insight into the complex realities of Latin America that have given rise to the temple project. My film employs what I refer to as “historical pre enactment,” a methodology that commingles fact and fiction, prophesy, and history. The work addresses the grandiose temple project through a vision of its future: does its construction necessarily foreshadow its destruction? Employing a powerful cinematic language, I used Inferno in order to collapse ancient histories of the Middle East with a surreal present unfolding halfway around the world.

The architectural medium has always had an essential part in predicting mankind’s future. The city to-come was the fertile ground upon which architects and artists of different disciplines sought to challenge reality, and to present humanity with an alternative urban vision.

In science fiction, the futuristic metropolis hovers between the good and the bad city, between a utopian ideal and complete dystopia. It presents the viewer with a fantastic urban layout but does so using familiar images. It expresses a sense of progressiveness and futuristic vision, while reflecting both the ambitions and fears of the times that gave birth to its idea.

The Cities That Were Not examines the relation of different representations of the city in science fiction to images taken from the world of visionary architecture. By taking the chronological timeline apart and re-assembling it, the City is experienced as a non-linear journey, in which past, present, and future simultaneously co-exist.