The Way We Survive

Curator: Irena Gordon

12/08/2021 -

11/12/2021

René Descartes argued: “I think, therefore I am,” namely mind precedes matter. Nevertheless, it is the corporeal body that is most often perceived as the essence of existence, and survival is the continuation of existence, expressing the eternal desire underlying everything, to preserve its “being,” as a manifestation of its oneness. While survival introduces an unequivocal antithesis: “to be or not to be,” modes of survival split into multiple channels: trivial and heroic, ironic and critical, realistic and imaginary.

Why contemplate survival? Due to the urgency to reflect on the bond between art and life today, as a vital necessity. The exhibition offers a metaphorical multifaceted mirror spanning situations, actions, and representations of survival: as a formative consciousness and an instinctive action; as a temporary state and an ongoing process; as a response to external occurrences and an internal mental-psychological mindset; as a biological-Darwinist struggle for the survival of the fittest, and as a philosophical reflection about what motivates us to survive, and for what.

The exhibition delves into the temporal and spatial dimensions borne by the experience of survival, with its diverse conscious and unconscious manifestations, the stories that follow, the forms and images it spawns. It examines how that experience is recorded in accumulated memories, engrained traumas, myths, dreams, and visions that blend with the so-called reality. All these give rise to the built-in tension between individual and collective existence, and the conflict between impulses of selfishness and self-preservation and values of empathy and compassion for the other. In the works of the twelve participating artists, the experience of physical, mental, and emotional survival lies, among others, in the survival of the images and in the meaning of the work of art as an existential act: in what ways does art function as an existential apparatus? How do images of the past dwell in the present, concealing the temporal dimension and the processes of recollection, while changing not only their form but also their aesthetic and historical significance? In an era of excessive imagery, perhaps visual representation is depleted, becoming extinct and losing its ability to convey any form of experience, whether survivalist or other?

In view of situations of great danger that require immediate response, physiological-evolutionary survival mechanisms elicit fight-or-flight (or fight-flight-freeze) responses. These mechanisms can be identified in many creatures; in humans they are often activated not only in situations of real threat, but also in those of stress and mental distress. Survival is thus explored in the exhibition not necessarily in terms of “to be or not to be,” but as a multiplicity of affinities between the world and the human body, between matter and spirit, and between reason and chaos. The exhibiting artists address the existential absurdity, the vitality and falsity innate to modes of artistic practice.

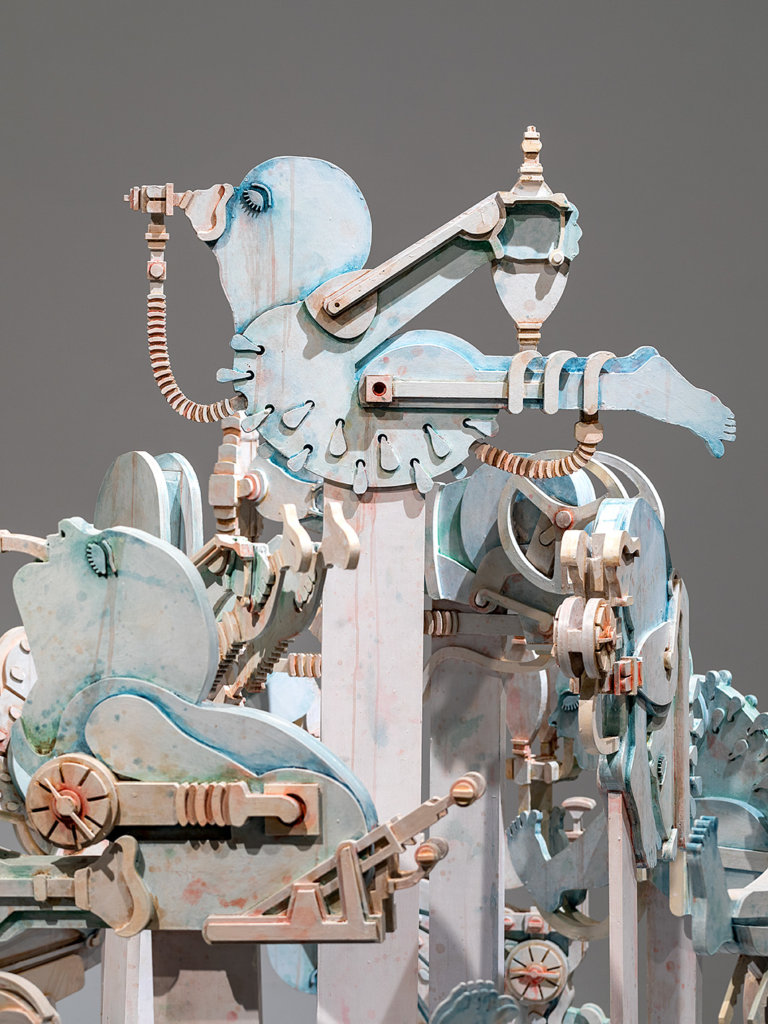

Aya Ben Ron’s carousel of fetuses on ventilators presents one eternal moment between life and death. This critical, paradoxical moment is set in the configuration of a childhood game, with carriages and horses in endless circular motion, which is associated with endless jouissance. Ben Ron’s carousel, however, does not move, and the lullaby that emanates from it signals the potential of movement innate to it, while creating a rocking that points to the deceptive boundary between sleep and death. The carousel is an allegory of beauty, difficulty, and unbearable pain, of life as a deterministic whole from which there is no escape. Fate cannot be controlled, and existence is imprisoned within processes foretold; nonetheless we persist in defending existence, the embryos details as sculpted, whole images, with their pastoral coloration, the conscious potential inherent in the material.

A First Aid leaflet created by Ben Ron for the first time in 2003 is presented in the exhibition in an updated edition as a printed issue. The illustrations in this work show pairs of bandaged, deconstructed figures in a hybrid state as one distorted body, barely distinguishing between the victim and the person offering help. The accompanying text consists of familiar guidelines for action in case of emergency, combined with ironic statements such as “avoid displaying over-identification,” or “first determine if a resuscitation attempt is actually needed. Performing a life-saving procedure on someone who does not need it is a waste of time.” At the same time, Ben Ron explores the irony and tragedy underlying human survival mechanisms, their fragility and meaninglessness. The ridicule, suffering, harmony, and innocence intertwined in her works present the inseparable link between the existential absurdity and the artistic absurd.

Vardi Bobrow presents a moving installation consisting of a large circular brush, whose long fibers, resembling hair, virtually lick the floor. The brush rotates clockwise, and its movement represents the passing hours and the changing times during the day. The brush marks the endlessness of time defined within the artificial, rigid structure of 24 hours. The four colors of the synthetic fibers from which the brush is made indicate morning, noon, evening, and night—white, yellow, gray, and black. During the rotary motion, the brush’s upper fibers seem to bathe the rest of the fibers with their color, the representations of the remains of the day hidden beneath them. The mass of fibers leans towards the viewer with all its weight, flooding him and weighing him down while seeking observation and inclusion. Not all fibers are visible, as it is not possible to see the light in all its phases at the same time. Just as we see the light of a dead star millions of years after it has been extinguished, so we will also see a black shadow-brush lying on the floor, held in a rusty ring—yet another brush that signifies the time that has passed.

The work was created by hand weaving in collaboration with the old brush factory in Kibbutz Ruhama—the sole supplier of brushes to the Israeli market for many years—as a tribute and a monument to the surrender of manual labor and the disappearing industries. The inspiration for the work came, among other things, from Kazuo Ishiguro’s 1989 novel The Remains of the Day, which deals with missing out and late disillusionment. The upright circle and the horizontal circle reflect each other, marking the identity of end and beginning in the processes of life.

On their way to Tamir Erlich’s installation, visitors encounter a plate-sculpture of ceramic nigiri-sushi on a ready-made kitchen stand, which is a refined representation of bourgeois Israeli cuisine. The wall of the “house,” however, has been breached clandestinely into the “exterior” space—a common space of a typical Israeli apartment building, which started out as immigrant housing and ended in neglect, improvised additions, and material encounters that produce a cacophonous aesthetic. The key element in this theatrical scene is a temporary wooden floor—a kind of deck, which is supposed to signify a life of luxury, but here it is made with deliberate negligence. A plastic pool is embedded in the floor, a ceramic fish standing on its edge, putting on a stand-up comedy of old and worn blunt jokes that emanate from an improvised home karaoke machine. Also on “stage” is a two-dimensional ceramic sculpture that simulates a home grill—another representation of the American-style suburban home, or the Israeli-style “detached house,” ideal. Cheap party lights twinkle under the floor, and at the far end, a bamboo fence towers, bearing a large engraved graffiti inscription spelling the name “Erlich.” Emphasized by a dramatic gesture, the fence symbolizes the centrality of the principle of takeover and ownership of land and space in the Israeli experience.

The term “fish love” indicates love that is no more than a projection of the subject’s needs, expressing the individual’s concern for him/herself and not for the other. Through that coinage, Ehrlich addresses survival in the practical, domestic, and everyday sense, highlighting the points of friction and conflicts in the encounter with the public space. The work, which draws on Erlich’s childhood memories in Holon’s Jesse Cohen neighborhood, deals with the effort of individuals to improve their status and living conditions both physically and symbolically, relating to situations such as lawbreaking, invasion, and occupation, tower and stockade, objection to disciplining and regimentation via creative means, and yielding to status symbols and fashion dictates.

Irith Hemmo’s dust drawings are traces of place, art, and life. Her works are formed from the passage of time, the perishable material, and the gradually fading memory of the image. By means of dust storms which she generates on surfaces of wood, canvas, and paper, she conjures up visual specters based on works from the history of Israeli art, which were part of the Zionist pathos of the establishment of the state, but have since been pushed to the margins of artistic consciousness. In her work here, she continues her dialogue with Mordechai Gumpel’s mosaic and sgraffito works, which adorned the Shulamit Hotel and the Dagon Silos in Haifa. Gumpel, perhaps the most important mosaic artist in 1950s Israel, found a social role and spiritual significance in art, and his wall pieces animated biblical scenes as an expression of the ideals of revival and pioneering.

For the current exhibition, Hemmo created a monumental wall piece that corresponds with Gumpel’s mosaics at Yad LaBanim House at Petach Tikva Museum of Art. The starting point for the dialogue this time, however, is not the mosaics themselves, but rather a small collage created by Gumpel in the 1970s. This modernist collage is abstract and intimate, rather than figurative and symbolist. In this choice, Hemmo seeks to take another step in exploring the survival of images and image remains as a motivation for artistic action, when she deconstructs and reassembles—to the point of multi-dimensional abstraction—an original which was abstract to begin with. This further undermines the possibility of grasping the forms and the relationships between them, while the disintegration and disappearance become the heart of the work whose existence flickers and shines from the void.

Israel Kabala creates a space that is a corpus of life and creation hanging by a thread. The installation simulates a sterile habitat in a laboratory of sorts, and at the same time—a ritual-shamanic setting containing mysterious pagan objects associated with the practice of art and its raison d’etre. All this against and inside a pictorial-drawing array in the making. In this hybrid space, chains of animate and inanimate objects are woven, coexisting in a symbiosis of construction and decay, injury and recovery, conservation and extinction, in an environment which is possibly natural, organic, possibly artificial, by virtue of its being housed inside a museum.

A ventilator and respiratory tubes channel carbon dioxide into a container in which aquatic plants grow, as the piston releases a bubble and a half per second. Each release is timed and counted, giving life to an organism that insists on living in artificial conditions. The board monitoring the bubble release is a kind of breathing map, tracing the walking, thinking, and action route of the “animal” in its new home in the museum.

The black ink basin and the water basin are akin to blood and spirit, flesh and life, and the pipes next to them simulate roots leading to the nibs of fountain pens; instead of ordinary pen nibs, however, they have porcupine quills at their tips. The quills ostensibly draw the actions on the wall, as a pulsating, breathing apparatus that insists on painting itself in the form of a painting of an aura of quills with a black hole in the center: the void from which all commences.

The “creature” is a work of art in the making, a living and changing calligraphic system. The artist’s breath, his essence, emanates from his mouth taking shape in the space. The painterly gestures evolving from this seemingly controllable system, which transpires between the artificial and the natural, embody the struggle between being and non-being.

Alit Kreiz created a guided audio tour for the exhibition. Equipped with an audio device, the visitor is instructed to observe the museum space and the works on view and experience them anew. The guidance, in the artist’s own voice, is the work of art. It prompts visitors to shuffle and redesign the connection between what they see in the exhibition and their familiar, inner world, to perform acts that deviate from the customary conduct in a museum, and to recalculate their personal choices between different behavioral patterns in contemporary society.

The work seeks the evolving human encounter between the viewer and the unchanging, inanimate exhibit. Via language and voice—as an artistic sound that penetrates the consciousness, resonates in it, and stays in one’s thoughts long after the occurrence, which lacks visual existence, ends— Kreiz tries to decipher patterns that shape the viewer-work relationship and locate a unique, evocative quality that will survive the encounter: What does the work leave behind? What do the viewers take with them? What remains and survives from these momentary yet physical relationships, precisely in an era of virtual and digital encounters?

The visual image invites the viewer to join it in creating a spatial whole—while the wandering, which yields to the sense of hearing, strives to reflect the way we act to present ourselves in space and leave an imprint in the other’s consciousness. Through their personal expression in the work, viewers can become reacquainted with themselves.

Karam Natour seeks to lose his identity, to separate it from himself, to observe it and furnish it with an independent, out-of-body existence. Natour—who was born into a Muslim family, was educated in a Christian boarding school in Shefa ‘Amr, and lives his adult life as an artist in a Jewish-Israeli environment—creates a visual index that weaves various identity markers together via manifestations of fluid, antithetical, intersecting personas, languages, and narratives. Through these narratives, drawn from Western and Eastern culture, from female and male gender signs, the Occult and its various magical and mystical manifestations, from popular literature, cinema and the Internet, Natour points to human existence as a multiplicity possible only in art and its underlying systems of representation.

The three works on display in the exhibition originated in a reflection on the Christian story of St. Veronica, who offered Jesus her veil to wipe the sweat and blood from his forehead on his way along the Via Dolorosa to Calvary, the place of his Crucifixion. Jesus wiped his sweat with the cloth, and when he returned it to her, the image of his face had been imprinted and fixed on it as a primordial iconic image (the name Veronica is derived from the Latin Vera Icon—true image).

Over the years, Natour has focused on digital drawing of his naked figure in various situations, faceless. In one of the works here, his features appear for the first time, as he holds the cloth—akin to Veronica’s handkerchief bearing the face of Jesus—next to a third eye, which in mysticism stands for prophetic vision. Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry from the Harry Potter books can be seen in the background, and at its feet is the uroboros—a snake or a dragon that swallows its tail. In the other two works the artist’s figure is absent altogether, while the mystical symbols appear in the center.

The title of the works—Volto Santo (Lat. sacred face)—was extracted from another Christian story that connects the act of faith with the work of art, and visual representation with divine presence. The legend tells of Nicodemus, a disciple of the Christian Messiah, who helped bring Jesus to burial and then sculpted his figure on the cross. Nicodemus fell asleep in the middle of the work, having sculpted the body of Jesus but not his face, and when he awoke he saw that the face of the Crucifix had miraculously appeared on his sculpture. Legend has it that the face was sculpted by angels—another acheiropoieta icon, not created by a human.

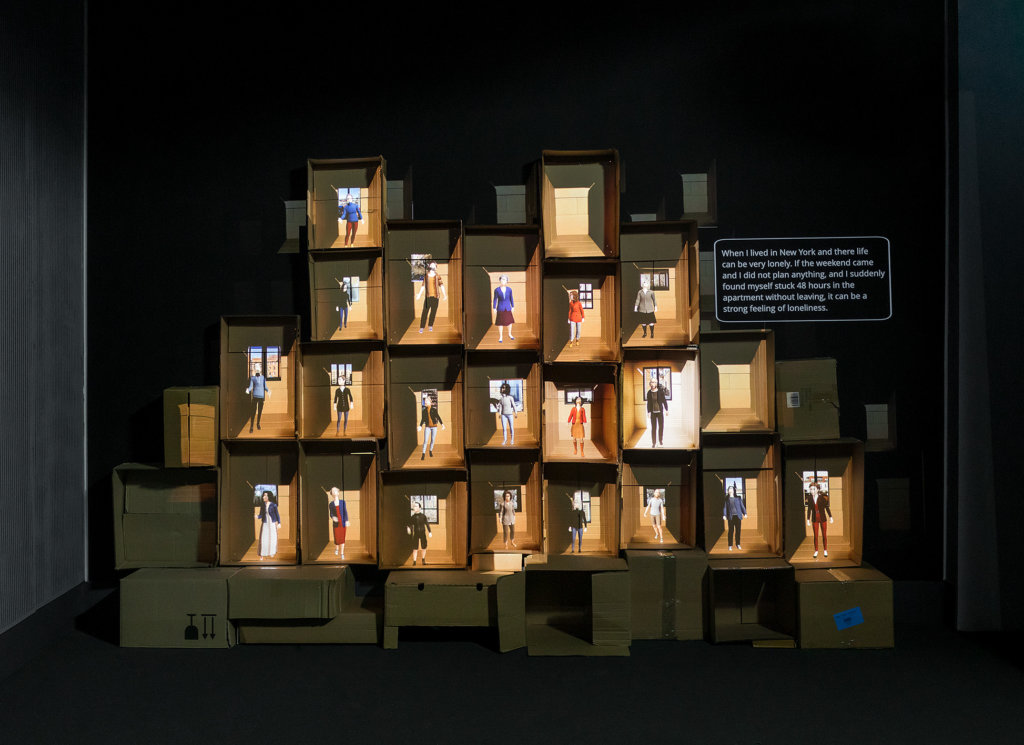

The work engages with solitude and isolation, inspired by a chapter in Hannah Arendt’s book The Origins of Totalitarianism, which refers to isolation as a common denominator that enables terrorism and serves tyrannical regimes, as a means of oppression. A common yet highly individual and personal experience, how can one describe solitude? This notion has been associated since the 19th century with the anxiety of non-existence, and in the 20th century was perceived as the epitome of modern alienation. Arendt sought to point out how loneliness helps the totalitarian regime to isolate man from society and cause him to act against others and against himself: “Isolation and loneliness are not the same. I can be isolated—that is in a situation in which I cannot act, because there is nobody who will act with me—without being lonely; and I can be lonely—that is in a situation in which I as a person feel myself deserted by all human companionship—without being isolated.”

Sharon Paz’s work is a collection of human voices from around the world, responding to questions regarding restrictions and distancing. Using avatars arranged in a cardboard box structure that simulates a high-rise apartment building, the sounds create a virtual three-dimensional space that touches on reality. The figures talk about different ways of dealing with situations of loneliness, as the video installation creates non-linear narratives from their words. The fragmented visual language and the skipping between figures which pop up intermittently in the different boxes, freezes the movement and creates tension—while the installation is adapted to the exhibition space and creates a dialogue of physical closeness with the viewer. The array as a whole raises questions about community and belonging, and about daily existence in a historical process that moves back and forth in time, between past, present, and future.

Are we facing a process of creation or erasure? Of subsistence or disappearance? In a series of intimate drawings, Assaf Rahat draws homeless figures, whom he meets on the city’s boulevards and alleys. The figures seem indifferent to their environs, indrawn, curled up to sleep on a bench surrounded by vegetation at the heart of urban bustle. Documentary in nature, the drawings strive to capture, in a brief moment of arrest, observation of people who have lost their whole world and are left with only the outdoors as a home, as their struggle for survival is exposed to all. One of these street dwellers is fused with a self-portrait of the artist, thus articulating the lurking danger and the fear of losing everything underlying human existence.

The homeless figures wander to Rahat’s series of paintings created in the medieval technique of egg tempera icon painting, consisting of natural pigment powders mixed with egg yolk, resin, and linseed oil, and applied to coarse burlap. At the focal point of the paintings is the figure of the artist, the one who lights a fire while looking at his reflection in the mirror and seeing himself burned, drowning, disappearing, and falling silent, succumbing to his hallucination. These fantastical works deal with painting’s reflexive quality as a district of dream and enlightenment, creation, erasure, and dissipation, as nature—the nature of painting itself—closes in on the figures, ostensibly trying to erase their existence, burn and drown them.

In its current version, the shack installation Napoleon 12A (originally featured in 2019 at the Acre Festival of Alternative Theater) addresses the historical appearance of the Napoleon transit camp (ma’abara) in Acre in the 1960s from a contemporary point of view. As someone who immigrated to Israel from Morocco and grew up in that transit camp—then a place of distress, and today a neighborhood of detached homes—Avi Sabag creates a new space of encounter between past and present, where archival materials intersect with personal memories, documents, photographs and voices of the residents themselves, and reports about the transit camp, which was among the last to be evacuated. These materials are combined with new works created by Sabag, including video and animation, sound and photography installations arranged in one artistic space centered on immigration and refugeeism, transience and non-belonging—in that place and in the universal human existence as a whole.

This personal memoir operates on two inseparable planes, the visual-photographic and the vocal, which consists of text, singing, and sound, mixing recorded voices with an especially composed original soundtrack. The various planes nourish and expand one another, while their boundaries are constantly challenged. They confront visitors to the exhibition with an endless encounter between the front of reality and the front of dream and fiction, between the documentary and the poetic-metaphorical—an encounter of fluid, elusive space and time, for internal and external exile is an ongoing state. The memory of detachment remains vivid in fragmentary, transient images, attesting to existence as a constant struggle between the conscious and the unconscious, between releasing and grasping. The images ask where the pain and fracture, the fears and anxieties, the happy childhood experiences and the traumas that shape our adult lives lie: are they embedded in distant voices, in objects that were preserved, in elusive dreams, or, perhaps, in dry bureaucratic documents?

In the years 1992–95, a bloody war took place in the heart of Europe, following the disintegration of Yugoslavia. Anri Sala and Liria Bégéja’s film—created as part of a joint project with Šejla Kamerić and conductor Ari Benjamin-Meyers—addresses the 1,395 days of Serbian and Croatian siege of Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia-Herzegovina. The inhabitants of the city were instructed not to wear colorful clothes at the time, to evade the snipers stationed on the nearby hills. Sala traces such a sniper’s route from a contemporary vantage point, as he follows a woman (played by Maribel Verdù) walking in the city, on her way to the orchestra’s rehearsal hall. At every intersection and crossing she must decide whether to stop or run, whether to cross alone or in the company of others. Elsewhere in the city, the orchestra is busy rehearsing Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony, commonly known as the “Pathétique.” The musicians play and stop, rehearsing various passages from the symphony, while echoing people’s movement in the city.

The woman’s journey through the city streets is not presented in chronological order, but leaps back and forth in time, with only the passages played marking movement forward or back. The woman hears the music in her head and thus finds the strength to keep going. The music and its connection to life in the film dictates a thought about the penetration of the past into the present and the recurring, critical interpretation of history in every present moment—much like learning, rehearsing, and re-performing the musical piece each time it is played. No dialogue in the film focuses on a single character fighting for its life, which is dictated by the rhythm of the work. The film thus captures the threat, violence, and fear caused by siege and war, and survival as the continuation of consciousness.

The work Canaries addresses memory and oblivion, and the attempt to bring them to the fore and introduce the connection between memory of the past and consciousness of the present through the visual and auditory means of video art. Jasmin Vardi’s two-channel video bypasses language by activating flashes of light pulsing at 40 Hz, which is said to cause the brain to release a surge of signaling chemicals that can help fight Alzheimer’s disease—a chronic degenerative disease that impairs memory. Simultaneously showing, the video Storm features palm trees swaying in the wind at the onset of a storm—exotic nature on the brink of a catastrophic occurrence.

Vardi weaves several narratives together related to exploitation and oppression, colonialism and war, as well as the dependent, survivalist connection between man and nature, man and animal: the mining of diamonds and other natural resources, which in some places in the world is still done by exploiting child labor; or the story of the canaries, which were brought to Europe in the 15th century by Spanish sailors, and served coal miners to warn against the presence of toxic gases in the mines. In this context, the phrase “canary in a coal mine” alludes to someone or something that is an early warning of an impending crisis; and the term “climate canary” refers to a species that is the first to be affected by environmental damage, thereby serving as warning to other species. Another key narrative focuses on the Barbary apes of Gibraltar—the tiny British territory at the tip of the Iberian Peninsula, which also controls the Strait of Gibraltar, that in ancient times marked the end of the world in the eyes of Europeans, and was an ongoing focus of colonial conflicts, myths, and legends. One legend has it that the Barbary apes reached the Gibraltar cliff from Morocco through a hidden underwater passage linking the continents.

Vardi intertwines shots she photographed in different places and times with found footage, constructing two similar yet different loops—documentary narratives repeated obsessively. This repetition, which simulates the processes of memory and forgetting experienced by everyone, reminds us which narrative we have forgotten or chosen to repress, forget, and send to oblivion.