The Space Between

Curator: Drorit Gur Arie

17/05/2007 -

06/10/2007

The interpretation of space in contemporary discourse has changed, becoming more complex and containing a diversity of spaces, associations and dimensions. Post-modern theories emphasize space as a major category with regard to modes of observing and understanding reality. The exhibition “The Space Between” strives to explore the museum space through new spatial perceptions that undermine the sanctity of the “white cube,” and vis-à-vis current artistic media that have changed the way in which we experience the artistic space.

The exhibition sets out to explore the relationship between the private space and the public space, against the backdrop of social and technological changes and their implications on the points of conflict and tension between them. The boundaries between the personal sphere, as a locus of intimacy, protection, at times concealment, and the public (museum) space as a site of exposure and as a field of power strategies and mechanisms, gradually become blurred. The exhibition opens up the definition of the museum space to a new reading, calling on viewers to challenge boundaries, conventions, and definitions of the space and the subspaces within.

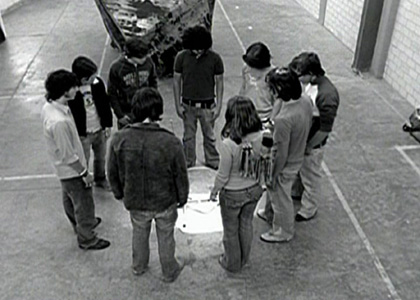

Adriana Lara’s work unfolds a staged pursuit of a group of young visitors to a space that appears like an art museum. The teenagers re-enact the gestures and actions expected of museumgoers, yet present them as meaningless stylized gestures, like a game of mimicking familiar norms of conduct in such spaces. The artifacts are likewise perceived as objects of illusion or deceit. Lara created the “artifacts” featured in the museum space over a one-year period. She also prepared instructions attached to each of the presented objects, and gathered excerpts from texts by art critics, artists, and philosophers, as well as cinematic dialogues which are played next to the works. The combination of different textual registers blurs spatial and temporal hierarchies. Lara’s manipulation blocks any attempt to generate a

single logical narrative of the occurrences. The alienated, calculated acts dictated by the script create a collagist text akin to a material and formal experiment. The Italian language and the black-and-white photography reinforce the sense of alienation and the work’s estrangement from a given original, as well as the ironic dissociation between what is heard and what is seen.

Karamustafa’s works explore self-identity. She often intertwines diverse materials, among them pictures and personal items charged with memories to encompass the notion of subject as well as personal and collective identity.

The work consists of two videos projected simultaneously on two screens; one depicts a family at home, whose everyday life is influenced by the occurrences portrayed on the other screen, unfolding a sequence of historical events in Turkey in the period between the 1930s and the late 1980s illustrated via documentary footage. Like a sociologist and an anthropologist, the artist explores the historical, religious and social contexts of her culture, often using materials that manifest the hybrid quality of her homeland.

Liav Mizrahi’s work generates a subversive act, introducing objects reminiscent of surveillance cameras into the museum space. He explores the issues of space and authority, the space’s regimentation via electronic means of control that have become a secret partner in our lives, gnawing away at the individual rights for the preservation of security and order.

Mizrahi uses an imposter-object to “duplicate” the main function of the “real thing” – invoking disturbing, threatening feelings in the space. He is not interested in creating an object that is “similar” to the original or to use a readymade. Mizrahi interferes with and undermines the authority of the sophisticated original device by making his cameras from simple, inexpensive materials devoid of real functionality. The foam board from which his “surveillance cameras” are made is a raw material for architectural models serving the artist to defy architecture’s aggression.

Once the impotence of Mizrahi’s “security camera” is revealed together with its inability to realize its assigned function and generate a photographic image, a closer look reveals it to be pathetic, emptied of its assumed violent powers. The artist launches a small-scale subversion, neutralizing the source of the threat from its power via a false duplication. Mizrahi’s work winks at the violent, intrusive gaze of the camera welcoming visitors to the museum.

Nadav Weissman’s pink wooden ship is chained like a prisoner, blocking, virtually strangling, the entrance to the odd shipyard. The adjacent room contains a single figure and a dog. The naked figure appears fixed to a splint; its gigantic head towers upward, and its small body, like that of a child, tilts down, seeking solid ground. The figure is disturbing, possibly crucified, certainly tormented. The dog stands on the ramp next to the figure’s head, and both appear to be inter-dependent, sharing the same terrible loneliness. Perhaps it is a wild, undomesticated dog, yearning for the realms of freedom and movement elsewhere. There is something heart-rending, and at the same time nearly ridiculous about this stuckedness, the silence.

Weissman’s ship seems to relate to a lost, unknown place; a house forgotten far away outside, or possibly deep inside. It alludes to a space that could have accommodated life, couplehood, a family. But the house is neither innocent nor warm. It goes up in flame, leaving behind pianos that make a narrow escape with the help of trucks. It is not at all clear whether Weissman’s ship can really sail off.

Nati Shamia-Opher assembles random materials, penetrating the empty space in order to plant therein small living spaces. She strives to peruse the tiniest basic territory existing at the friction point between the individual and the space, a moment before the private territory disintegrates, leaving the individual exposed to the public sphere. The need to create personal spaces of survival within public enclaves results from the mobility characterizing globalization. Whether economic mobility or forced mobility due to political or social migration, it ruefully designates homelessness. Shamia-Opher explores instances allowing the public sphere to contain “pockets” of private spaces

Industrialized construction and its materials are replaced by industrious, improvised female handiwork. The “construction methods” are copied from disciplines of textile and confection, and the solid, stable materials assume qualities of rawness, softness, and resilience, and are readily-mobilized. Shamia-Opher explores the affinities between clothing and architecture – two disciplines which produce “structures” that wrap the body, isolating it from its surroundings and marking a physical and psychological borderline between man and society, between the private and the public.

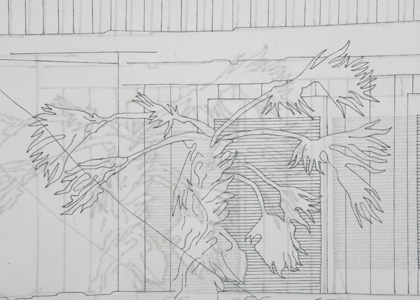

Ofri Cnaani’s video presents the contemporary city as a threatening entity operating as an anonymous force of control mechanisms that govern the individual’s everyday life. The work unfolds a heroic journey taken by the protagonist in a trauma-stricken metropolis. Cnaani’s city, equipped with mechanisms of control and supervision intended to reinstate security, becomes a hostile arena endangering the protagonist’s soul. The artist presents the post-modern city’s means of protection and control mechanisms as mythical monsters that must be fought mercilessly. Her quest alludes to the heroic journey of Heracles, the mythological hero, Like him, Cnaani’s protagonist marches through the city streets, head held high, dragging her spoils: birds’ wings, a lion’s head, a cardboard dog, and a monumental flag. The sights and sounds in the work spawn the image of the city as a multi-eyed, all-seeing entity that expropriates its inhabitants’ private sphere, undermining their rights to free movement and privacy.

Oreet Ashery explores the artistic space. This time it is the artist’s studio – the private, intimate space where the work of art evolves before it goes to the public exhibition space. In the first part of the video Back in 5 Minutes Ashery uses her private studio in a stuffy London basement to discuss artistic space. The work unfolds the story of a curator visiting/invading an artist studio while the artist is absent. The second part of the work, screened in the same space and concurrent with the first, depicts a conversation between the curator and his wife. The artist’s disappearance is introduced as a detective story a-la film noir. The unusual installation of the video piece in the museum basement expands the boundaries of the work, creating a story within a story. The artistic storage area trickles into the virtual studio, blurring the boundaries of the artistic space and the place of spectator and curator.

Raphael Cohen and Nitzan Sat’s architectural-artistic project introduced a corridor-like foreign body into the museum, upsetting its space and governing the visitors’ route. Employing acts of duplication and reproduction typical of contemporary architectural planning, Cohen and Sat’s intervention in the museum space alludes to the undermining of two types of spaces: the home as a protective locus, and the hierarchical, alienated modernist exhibition space. In its beginning, their corridor appears like an emblem of lean, ideological, functional modern architecture. As it extends, however, it turns out to be a type of reproduced architectural object inserted into the exhibition space repeatedly with neither spatial logic nor a clear purpose. The need to penetrate one space, and pass into another, becomes a game of sorts, both random and threatening. The issue of “transitional spaces” surfaces as the viewer comes up against walls and barriers on the one hand, and open spaces on the other; neither advances him to his target – namely understating his relationship with the space, and the relations between the space and the works of art featured in it.

Ravit Cohen Gat’s work marks within the museum space a domestic sphere intended for female mourners. It enables the outsider (the viewer) to penetrate the intimate mourning room, transforming the public domain (the museum) into a private sphere. Thus, the exterior permeates the interior, and the personal loss is exposed for all to see.

The space created by Cohen Gat is not a sanctified sphere. She exposes the processes generating emotional rituals and the manipulation underlying bereavement. The viewers/consolers crossing the threshold can barely perform the rite of mourning due to the fabric sheets that hang down to the floor, limiting movement. The wailing sounds emanating from the amplification systems expose the technology generating them, “industrializing” the mourning customs.

Azari’s work sketches a cold, cruel and indifferent world that allows the horror to occur just under one’s window. Azari’s window assumes a psychological-cognitive as well as socio-political air. The viewer observes the threatening, violent “outside” from the couple’s protected “inside.” The different spaces are unified by the voices, which also generate the cognitive gap between the sentimental bubble and the cruel external reality.

The video’s seemingly simple plot is typified by the intricacy of three simultaneous spaces and the ironic discrepancy between them. The artist destroys the possibility of isolation as a coefficient of existential security. Azari’s critical window forcefully draws our gaze to the immediate outside, where the gap between the American dream of power and happiness and a reality of alienation, vanity and evil is gaped open.

Tal Amitai addresses the domestic sphere, operating as a shaman attempting to “rectify” and “rehabilitate” crumbling house skeletons hanging by a thread. Her fetishist archive of images contains photographs of house residues that collapsed due to natural catastrophes or wars, images which she collects from websites and magazines. The artist “inscribes” an architectural image of a house in New Orleans crushed by the hurricane Katrina with black sewing thread, via an obsessive industrious act. She processes and enlarges the digital image in Photoshop. As in needlework, she gradually infuses it with new life, constructing it line by line (as if she were laying brick on brick) from strips of fine thread attached to a transparent Plexiglas surface. The assemblage and construction masquerade as an act of sewing, yet Amitai exposes the artistic manipulation by leaving unstitched threads on the surface, like a broken brick wall. The demanding, intimate labor spawns an enigmatic space infused with life, where the memory of the house that was, with the totality of its physical and metaphorical strata, is at once present and absent. Amitai exposes the far-fetched nature of the home, house, and family as a solid foundation of security, stability, and happiness. The house is an illusive, thin and fragile cover where memory casts a heavy shadow and where fears are concealed.