Take Painting

Artist-curator: Larry Abramson

15/09/2016 -

24/12/2016

Painting is as old as human culture and as young as a newborn baby. It bears the accumulated knowledge of generations as well as the nameless, formless primary desire of the body to mark its existence in the world.

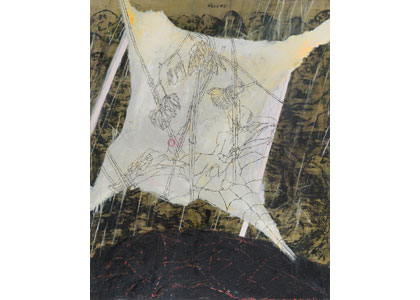

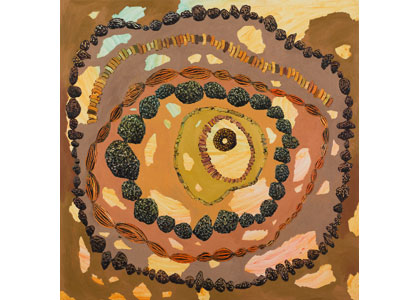

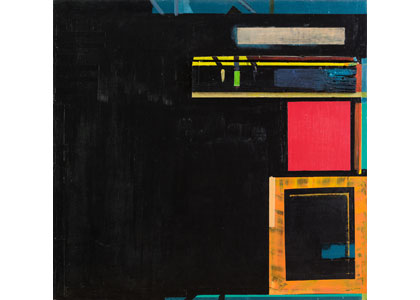

Centuries of construction, deconstruction, and reconstruction have formed painting as a site of repeated assembling and disassembling, an archaeological mound of sorts whose strata not only pile up one atop the other, but also— mainly—mix up into each other. Multiplicity, contradiction, and simultaneity have become the hallmarks of the new painting. Painters today brush off the melancholic lamentation over the collapse of the utopian modernist order and dive passionately into the pile of history, joyfully burrowing amidst the remains of languages and images cast there in a jumble, choosing those most fitting at this given moment for the creation of an improvised order of their own.

The pile of painting contains countless empty signs, displaced leftovers from the studios of painters and artisans from different periods and cultures, but also from the nonstop contemporary production line of digital advertising, communication, and game images. Of all the findings in the pile, however, the most exciting today seems to be abstraction. Many painters in Israel and all over the world are shaking the dust off the remains of abstract languages discarded into the refuse pile just a few decades ago, discovering in them—and in their combinations— an actual and relevant aesthetic and allegorical potential. Moreover, even those who choose to work today with the remnants of figurative languages find in the abstract composition the most suitable space in which to organize fragments of images into one homogeneous painterly space.

The paintings in “Take Painting” are not romantic representations of ruins observed somewhere out there in the landscape; they are themselves ruins—composite sites of the real and the allegorical, hybrid accumulations of abstract and figurative idioms, tentative stacks composed of remnants of ideologies and fragments of dead languages, an aesthetic experience that also offers a vantage point onto that which the allegory of painting points to—the world outside the site of painting.

Larry Abramson

Photography and video editing: Gili Meisler – meisler.com