Set in Motion

Dance-Art-Community, Curators: Drorit Gur Arie and Avi Feldman

22/05/2014 -

06/09/2014

The Hebrew title of the show, “Confidence-Building Measures” (“trust-building steps” in literal translation from the Hebrew) is borrowed from the field of political science and international relations, where it indicates actions taken to reduce tension and minimize suspicion between states. The attempt to arrive at a common denominator and dialogue between ostensibly foreign publics is also the motivating force behind the current exhibition, which transpires on the line between dance and choreography, art and the museum.

The public sphere—and the museum and gallery as a part of it—is not foreign to contemporary dance. Since the 1960s in particular, many choreographers and dancers have challenged previous traditions and performed dance pieces outside the stage, whether in an art museum or on a building’s rooftop. A pioneer of this trend in contemporary dance was the Judson Dance Theater, a collective established in New York in 1962, whose founders included renowned choreographers Yvonne Rainer and Trisha Brown. Additional dance practitioners and artists from other fields operated concurrently, among them Merce Cunningham and visual artist Robert Morris.

The exhibition, the first of its kind in Israel, observes the renewed penetration of dance into the museum space today, and strives to direct its gaze at this present moment. It focuses on the choreography’s pulse and the stratification of contemporary dance in relation to the museum’s white cube, to alternative venues, and to collaborations with visual artists, which facilitate the establishment of language and thought, and the formulation of a new dance discourse. At the same time, this process also calls forth a reconsideration of the museum’s status and role.

This channel thus joins an ongoing scholarly process carried out at the Petach Tikva Museum of Art, which has followed artistic practices in the context of social action. Albeit infrequent in contemporary Israeli dance, in these frames dance stands as an equal alongside the visual arts, striving to exhaust the potential inherent in the medium in elucidating and promoting political and social goals.

Based on the two major axes—community and the public sphere—the featured works turn a critical gaze at the body’s power and failures; they examine dance as a vehicle for constituting and defining a community, analyze the relationship between spectator, movement, and object, and confront the challenge posed by the moving, living body to the prevalent frames of museum presentation, collection, and archive. The works selected for the exhibition were created by choreographers who have made site-specific works for a museum space for the first time, as well as by visual artists for whom dance is a means for personal reflection or communal action. Simultaneously with the exhibition, activities in the public sphere will be held in collaboration with the Petach Tikva community.

Drorit Gur Arie and Avi Feldman, co-curators

With sing-alongs, folk dancing—a popular practice in many different societies and cultures—is a key stratum in Israeli culture. Dancing became a prevalent local social custom in the pre-state pioneering culture, and the Hora became an emblem of Israeliness and assimilation in the land.

In a sports arena in the present day city of Kfar Saba, against the backdrop of a gloomy sign announcing “Israeli dance,” men and women dance in circles, caught in an ostensibly obsolete world. Their steps strive to continue a seemingly age-old eternal tradition. Paired off in couples, they dance on, reinstating the belief in unity and collectivity into our lives.

Through the interruptions and manipulations performed by Alona Harpaz by means of sound distortions and close-up shots, a multifaceted picture unfolds before us, accentuating the unique, solitary presence of the photographed figures. They hold onto one another, drawing nearer and away in keeping with the dictated step frame and the changing music; but what are, in fact, the sounds sending the dancers toward one another? What is the imaginary reality for which they yearn as they reach the dance floor? Can we too share the same place, time, and ideas wrapped in the circle’s protective cloak?

The camera captures the artist’s feet as she puts on her old ballet shoes that she has had since childhood, offering a reminder of bygone days, years after she gave up dancing in favor of the visual arts. Subsequently, she is swept into constant en pointe dance movement against the backdrop of the studio interior, crammed with equipment and art works in progress, whose atmosphere oscillates between the amused and the rigid. Her movements through the studio are interwoven into a powerful metaphor regarding the need for self-restraint, combined with unexpected moments of creative surge, extreme tension to the point of physical outburst, release, and loss of control. The video’s length (5:50 min) is identical to that of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Concerto No. 1 for Piano and Orchestra in D Minor.

Archive materials (left screen): volunteers for the “Camera Project” of B’Tselem – The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories – Ahmad Jundiyeh, Issa Amro, Abd al-Karim J’abri, Abu Ayesha, Raed Abu Ermeileh, Iman Sufan, Mu’ataz Sufan, Mustafa Elkam, Oren Yakobovich / Videography (right screen): Amir Bornstein / Video consultant: Effi ana Amir (Effi Weiss and Amir Borenstein) / Artistic advisor: Katerina Bakatsaki Since the establishment of the Human Rights Movement, and chiefly since the increase in its international impact in the 1970s, quite a few artists have joined its ranks and have been identified with the voices calling for social change. In the field of dance, early signs of this trend may be found, for example, in the influential works of Martha Graham, a pioneer of modern dance, such as Chronicle (1936), which alluded, inter alia, to the Spanish Civil War, or American Document, which was conceived in response to the social-economic-political crisis in the United States and the world over, and debuted in August 1938. One critique frequently aimed at “postmodern” contemporary dance—which is also valid in the context of Israeli dance today—is that it no longer addresses the burning issues and has shut itself off as a self-occupied reflexive medium. In light of this, the work of Israeli choreographer Arkadi Zaides, who explores the impact of the political sphere on the body, stands out in the local artistic landscape. The original use of archival materials to create a semiotic history of movements, as arising from the gestures of the documenters and documented in Capture Practice, brings questions concerning the ways in which choreographers use visual documentary materials into sharper focus, also shedding light on the transformation of the human body itself into a living archive. The dancing body, which frequently remembers or recollects sights, images, and thoughts, demonstrates without words the horror of crisis, and the tribulations and fear which are the lot of any individual living under ongoing conflict. Capture Practice is based on the “Camera Project” launched by B’Tselem – The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories—which equips Palestinian volunteers living in the Occupied Territories with video cameras to document their lives and human rights violations. In the archival materials used in Zaides’s work, the photographers are, as aforesaid, mostly Palestinians, and the photographed subjects are Israelis.

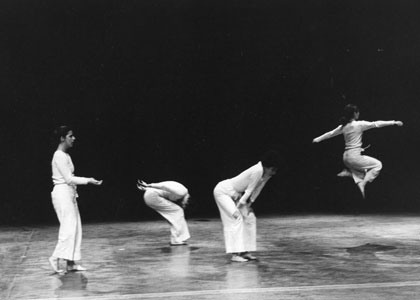

Babette Mangolte has followed the development of contemporary American dance since the early 1970s in her presence, work, and gaze. Her photographs and films provide close testimony for the key moments in which choreographers and dancers, such as Yvonne Rainer, Trisha Brown, or Steve Paxton, have reshaped the perception of the art of dance.

The series of photographs screened here spans images extracted from pivotal works, such as Rainer’s 1972 performance at Hofstra University, New York; Brown’s 1973 performance in Central Park; or a 1977 solo dance performed by Paxton. With emphasized slowness, image after image, the history of contemporary dance unfolds before our eyes, without falling into the trap of the heroic or venerated, in the spirit of Rainer’s No Manifesto from 1965 which advocated “No to spectacles. No to virtuosity.”

Dan Graham’s work, which spans many different fields, including photography, performance art, video, and writing, touches upon the interim realms between art, architecture, and society. One of the most outstanding practitioners of conceptual art, Graham defines himself as a “gifted amateur.” Departing from this point, he has created a fascinating analogy between rock music and religious practices in the context of contemporary culture. Graham’s analysis of rock music and its features verges on ethnography, since his film documents “iconic” figures, cultural heroes. Following several essays about the affinities between rock and religion, the work Rock My Religion delves into the phenomenon, exploring issues pertaining to body, gender, sexuality, and woman’s status in the field of rock, intertwined with an engaging study of movement, performance, and dance, which are an integral part of both religion and music. Power, sexuality, and trance have deep primordial roots, which may explain how rock music so forcefully penetrated performance art and the artistic happening since the 1970s, and why it also infiltrates contemporary dance.

Produced by Association Cie Projet 11, commissioned by deSingel theater Belgium, with the support of: the Swiss Arts Council Pro Helvetia; Migros Culture Percentage, Switzerland; the City, Republic and State of Geneva; Goethe Institute, Germany The work of the MAMAZA collective, comprising renowned choreographers, explores the affinities between culture and the public sphere in an attempt to define a community. In recent years the group has operated among local communities in different cultures around the world, striving to examine the power of the visual arts and the performing arts in advancing knowledge and social change. A red line, intended to link and connect, is stretched from the world of the dance stage or cultural center to the public sphere, as the choreographers leave the stage for the street, enter houses and meet with the locals, together identifying points of contact and connection. By drawing the red line, which marks the body’s movement between the various spaces, they strive to abandon the stage momentarily and delve into vital preliminary questions: In what ways do contemporary audiences relate to cultural centers? What ties the world of the stage to the metropolis around it? What is the choreographic meaning of the red line created in the public sphere? Thus far, group members have marked over eight kilometers of red line in various cities in Europe and Africa. This is their first activity in Israel, where they stretched a red line between the Petach Tikva Museum of Art and the urban sphere around it. The line is a physical-mental link between communities and cultures here and worldwide. As such, it embodies questions of identity, mobility, nomadism, localism, and globalism.

The work of Italian artist Marinella Senatore is a unique test case of “social art,” a fascinating combination of contemporary art with a type of social work. In recent years she has worked on the extensive project The School of Narrative Dance which attests to the growing curiosity among visual artists regarding the possibilities inherent in dance as a social vehicle. Senatore is distinguished by an inspiring ability to gather a multi-participant community around her, and the unusual attention she lends to conversations, workshops, and unmediated encounters with the local citizens of each place in which she operates, constructing the plot of her work through their personal stories and in collaboration with them. By working with other choreographers, Senatore goes out into the “field”—whether a low socioeconomic status neighborhood in a provincial town or the rehearsal rooms of a pensioner orchestra—and recruits thousands of people to active creation. Participation in Senatore’s projects is open to people at any age. The artist trains the participants to serve in a range of roles: extras, lighting men, and even choreographers, scriptwriters, or co-directors. The current exhibition features the operatic trilogy Rosas, which presents Senatore’s modi operandi in film, video, and drawing. For its execution she was joined by more than 16,000 people from Berlin, Derby, and Madrid, who took an active part in the production and participated in a wide range of workshops, conversations, and meetings combining hands-on work, writing, singing, dance, and movement

Born in 1886 in Hanover, Germany, Mary Wigman began her dancing career at the age of 24, and three years later created Witch Dance. A milestone in the development of Wigman’s art, which is associated with German Expressionism, in this short piece she anchored her perception of dance in an aspiration for dissociating the “necessary” coupling between music and dance, and set out to subvert conventions of beauty, by conceiving of an “ugly” dance. Wigman strove to combine two antithetical vectors in her work: arrival at a state of trance, while maintaining full control of body and emotion. Wigman’s influence on modern dance has been extensive, and it is particularly evident in Martha Graham’s choreography, followed by Pina Bausch’s work, and even that of Butoh artist Kazuo Ohno. Today some tend to minimize Wigman’s part in the history of modern dance due to her “collaboration” with the Nazi regime and the choreography for a youth dance she created for the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games.

Mike Kelley traces the origins of renowned choreographer Martha Graham’s dance gestures, thereby generating an extensive, breached associative sphere. He incorporates mythological dance pieces by Graham with movements derived from the experiments by psychologist Harry F. Harlow in the 1960s on monkey behavior. In addition, he relies on the studies and films of behavioral psychologist Albert Bandura on the effect of televised violence on children.

Originally, the installation was shown enclosed in a metal cage, and an elevated ramp enabled viewers to take part in an experiment of dance and objects observed from above. The cage, which in this context calls to mind a menagerie, also alludes to Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, which allows control and power through surveillance. The introduction of dancers into the panopticon-like cage arena reinforced and enhanced the known alienation in human relations with animals and objects, challenging the work of the studied psychologists.

Originating in the Ivory Coast, the Mapouka is a group dance primarily performed by women, usually with their backs to the audience. Its most conspicuous feature is the dancers’ leaning forward, while shifting their weight to the toes. In a slow rhythm of heel-raising without hip movement, the women perform a dance which accentuates and focuses the movement and presence of the buttocks. Despite these characteristics, which may be read as erotic, the dance is performed by women young and old, and even by girls. The Mapouka does not differ from other prevalent dances which invoke and undermine various perceptions regarding culture, gender, sexuality, and control in the viewers’ consciousness. Thus, for example, presentation of Mapouka on television was banned by the Ivorian military regime on the grounds that it was a harmful evil. Fear of body politics and the power of dance, however, is not exclusive to Africa. Mark Twain denounced the Can-Can more than 140 years ago, and popular dances such as the Twist and the Tango were initially deemed vulgar, indecent, and dangerous. Nevet Yitzhak’s work returns to the ritual origins of ancient popular dance, while relating to the Twerk dance which has become a media phenomenon in recent years and is considered a Western version of the Mapouka (twerking is usually performed by women to popular music in a sexually provocative manner). Yitzhak explores the affinities between these dances, and the intricate cultural references to pelvic thrusting in terms of the objectifying gaze and self-righteous moralization. She strips the movement until it becomes amorphous and internal, while the voiceover—alienated and cold as anthropological research—presents the Western gaze as classifying, excluding, or appropriating. Dance is thus examined in contexts of folklore, ideology, and apparatuses of social disciplining.

In his dancing wall installation, Sergio Prego takes a critical look at the influential early work of dance artist Trisha Brown who, inter alia, used to “dance on walls” in public places (Walking on the Wall, 1970, and Man Walking Down the Side of a Building, 1971). While Brown, however, endeavored to liberate dance and the human body from the limitations of gravity, time, and place (her dancers were tied to the walls of buildings and museums during the performance)—Prego’s work possibly continues this inclination, possibly ridicules it. Shifting the movement to the white walls, while leaving the gallery space empty of presentation, Prego in fact explores basic notions in modern and contemporary dance and visual art, while alluding critically to the status of the museum and the viewer’s place in the equation formed by museum, artist, and work. As such, he re-defines the status of the work of art in a world dominated by capitalist market forces and by the “official” written history crowned by artistic discourse.

In her first film, Tracey Emin tells us in her own voice, with melancholy or perhaps rage, about her adolescence in the forsaken English seaside town Margate. Having dropped out of school at 13, Emin spent her time in the beach cafés, having casual sex with teenage and older men, which she initially perceived as simple and accessible. Eventually, however, she felt that she had slept with everyone, and that the city was too small for her and all its citizens appeared miserable. The dance floor functions as a platform on which to express her feelings and her great adolescent vulnerability. Emin, who later became a successful artist, uses the language of dance to talk about success and failure, and about the links between life and art.

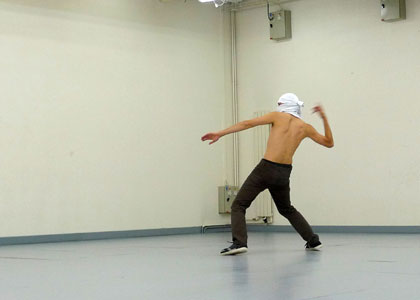

Since her return from New York fifteen years ago, Yasmeen Godder has been one of the most outstanding choreographers in Israel. She works with artist and dramaturge Itzik Giuli, and is known for her collaborations with visual artists, among them Gal Weinstein, Alona Rodeh, Yochai Matos, and Tamar Lam. The dance piece presented here, created especially for the Petach Tikva Museum of Art, is her first experience with site-specific work intended for a museum interior, attempting to define a new space for the intricate dialogue between viewer-object-body-space-time-movement. The prolonged work, approximately three hours in length, will be performed by Godder’s dancer, intermittently, in the museum space, throughout the duration of the exhibition. The dance piece came into being alongside and combined with objects from her previous works, and juxtaposed with video pieces by several other artists. Godder creates live performances alongside still objects, exploring how dance pulsates when it converses with visual art. Like the objects and works of the other artists, the new dance piece stands on its own right, while at the same time it may be given a syncretic reading along with the other exhibits to generate a unique whole, gradually evolving, changing, and consolidating until the show’s closing. The work was developed via reflexive hindsight—a gaze which is not retrospective by essence, nor strives to reconstruct earlier works. Instead, it is an intense process of decontextualization, while plunging into the archive and revisiting works created by Godder in the past fifteen years, extracting physical, emotional, communal, spatial, and conceptual peaks. The work evolved from the exhibition’s underlying concept and its two major axes—community and the Museum as a public sphere. The shifting of Godder’s Jaffa-based rehearsal room to the museum triggers questions about the constant tension between the communal-popular space and the hall of muses. http://www.yasmeengodder.com/ – For additional information and details about performance times, please contact the museum.