Recalculating Route

4 Mediations Biennale, Poznan 2014,Curator: Drorit Gur Arie

02/10/2014 -

24/01/2015

The exhibition “Recalculating Route” is presented as part of the 4th international Mediations Biennale Poznań, Poland. A joint frame of art events and exhibitions held this year in 14 cities around the world under the umbrella title “Post-Globalism,” it strives to create a network between different, remote cities, including New York and Hiroshima, Istanbul and Hanover, Petach Tikva (Israel) and Maputo (Mozambique), San Diego and Montevideo (Uruguay). The Biennale’s subtitle, “When Nowhere Becomes Here,” reflects the confusing current state of affairs in which countries strive to maintain geographical borders and national identities, and at the same time transpire as active players in a global market which threatens anything perceived as “local.”

The roots of globalism go back to the years of the great migration of nations in the Middle Ages, extending all the way to our time, through the exploration of continents in the 15th century, the Industrial Revolution in Europe and the height of colonialism in the 19th century, which established an economic and cultural Western hegemony in the spirit of progress and modernity around the world. At the end of the 20th century, in the wake of the Cold War and the fall of the Iron Curtain, globalization processes presented themselves as an extreme realization of colonialism, which dissolves cultural distinctions and subordinates East and West, center and peripheries, to the values of democracy and liberal economy. In our post-global present, however, it is rather the hegemonic centers that seem to disintegrate from within as if they contracted an autoimmune disease.

The digital revolution created the illusion of a world without borders and a promise for freedom of movement for people, commodities, and information; today, however, it has already become clear that the ramified commercial and virtual connections and the tangle of multinational economy have introduced an old-new colonialist oppression under the auspices of international law. Forecasts today appraise the number of migrants moving around the world to reach approximately one billion in the next fifty years—an unprecedented emigration crisis that will shatter entirely the distinction between permanent urban habitation and nomadism. Will the accelerated movement free mankind or will it rather lead to new slavery which objectifies people as if they were commodities? What kind of geography will be created in a world whose borders are fluid? Perhaps this state of affairs introduces us to a new opportunity: the ability to constitute a geography of dynamic identities in which each subject is required to constantly navigate between numerous forces.

The exhibition reflects the experience of transition to a disillusioned post-global world in the work of contemporary artists who function as double agents, oscillating between the local and the global, tradition and innovation, nationality and internationality, creation and production, labor and goods. It proposes a journey between real and imaginary realms, between textual routes of movement and sights which float in unison on the scanner of the collective unconscious. It echoes epic quests (from Odysseus to Gulliver) in the regions of the imagination and spirit, alongside real journeys of exploration, conquest, and commerce. Unfolding amid the voyage images is the sea as a multifaceted site where the real implodes into the virtual, a refuge of imagination and fantasy for the physically bound and those unable to move.

Soviet director Aleksandr Ptushko’s feature The New Gulliver was released in 1935 and was one of the world’s first films to combine live-action footage with stop motion animation. It is an adaptation of the story of Gulliver’s Travels, who in the Communist version is replaced by a young boy. Jonathan Swift’s book, originally entitled Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World (1726), set out to challenge the social order and expose society’s hypocrisy under the guise of a fictitious plot, a parody on travel literature in an era of explorers and discoverers of new territories in America, Africa, and Asia.

In Ptushko’s film, the youth Petya, nicknamed “Gulliver” by his peers at a camp for young pioneers—listens to his counselor reading from Gulliver’s Travels. He falls asleep and wakes up as Gulliver, a giant “man-mountain” bound to the ground in the land of the Lilliputians; a faraway kingdom now populated by a decadent bourgeois society ruled by a tyrannical absolute monarch. Gulliver sides with the king’s oppressed subjects in their struggle to overthrow the regime.

Amir Yatziv’s work refers to the Voyager, an unmanned exploratory spacecraft (probe) launched into outer space by NASA in 1977. A Golden Record with stored images and sounds representing the diversity of the species and cultures on earth was put on board as a message for intelligent extraterrestrials in case the Voyager encountered them at the conclusion of its journey, 40,000 years later. The collection of images (e.g. of luminaries, architectural and cultural treasures) and natural sounds (such as those made by various animals, ocean waves, wind) was complemented by a selection of music from different cultures and eras, and by greetings in 55 different languages, including Shalom in Hebrew. Signs providing scales of time, size, or mass were attached to many of the images, as well as instructions and explanations regarding ways to reconstruct and retrieve the encoded data, although chances of hearing these sounds in outer space conditions are virtually nonexistent.

The title of the work was extracted from an official statement recorded by the then American president, Jimmy Carter, which was also included in the record. It attests to the hybridization strategy typical of Yatziv’s work, who makes foreign connections of visual images with text and sound. Here he created a quasi-readymade of the record’s original soundtrack playing on a phonograph without being heard. The record player is covered by a bell jar connected to a vacuum pump that sucks the air out, creating a vacuum around it which prevents the creation of sound waves, thus no sounds are heard. Under his simulated outer space conditions, Yatziv toys with the creation of a futuristic encounter which destroys itself in the lack of apt physical conditions, thereby challenging the simplistic story which presents civilization and the history of mankind as a time-space capsule devoid of real communication and repercussions. The symbolic gesture of the human message that dared go further than any other, far beyond the moon and Mars, is exposed in his work as hollow, absurd, and futile.

“One day, when I opened the fridge, I found myself looking closely at the information on a can of pineapple. It was made in the Philippines, packed in Honolulu, distributed in San Francisco, and the label itself was printed in Japan. It was a perfect illustration of global, transnational economy.” With this recollection, Amos Gitai describes the theme of his documentary Ananas (Pineapple), which addresses the ideological and human repercussions of globalization processes by tracing the history of canned food. It is an anti-romantic travelogue whose contradiction-ridden texture comprises sounds and sights which tell the story of economic domination of Third World countries by a multinational, US-based corporate giant.

Gitai is among the most fruitful and esteemed filmmakers worldwide. Nevertheless, his films are often unsettling due to the radical socio-political stance underlying them, which sets out to deconstruct the prevalent social superstructures. In Ananas (Pineapple) he inventively enacts a Marxist problem: the commodity’s status as a fetish, an object whose presence in the world is ostensibly neutral, but in fact conceals an entire web of history, power relations, occupation, and exploitation.

The film’s power lies not only in its contents and “investigative journalism” qualities, but also, mainly, in its unique artistic language and the way in which it challenges documentary conventions. The film is perceived as “arty” as a result of Gitai’s use of expressive means such as lengthy pan shots, generous response time given to interviewees, unusual adaptation of the soundtrack, and carefully laid-out interrelations between soundtrack and picture. In his avoidance of voice-over narration which would have interpreted the involved parties and plot, the director also avoids ethnocentric judgment, passing judgmental responsibility to the viewers.

Shredder consists of cogwheels pivoting around an axle like organs of a ramified machine. In effect, however, they are dissociated from any function or productive mechanism, and are not nourished by any external body. Random and arbitrary, their movement declares that they have become their own purpose, like an incorporeal autonomy announcing “deus ex machina.”

One of the most important inventions in human history, the wheel is an essential, vital means of transportation, conveyance, and industry, which forms a concrete representation of the system of balances at the core of physical existence and civilization. Eyal Assulin’s work sheds light on this insight as part of a post-apocalyptic vision which pushes the constantly accelerated and radicalized race for technological progress to the extreme. The global race no longer strives to serve humanity’s true needs, nor is it subordinated to ethical questions regarding worthy conditions of existence. The wheel, like progress on the whole, has entered a whirling race against itself, gyrating with a squeaking growl around its narcissistic axis. As in the case of Marcel Duchamp’s castrated machines, the human is none of its concern.

O.R.B—an orbiting spherical celestial body—is a work about travelling within the time and space in which it takes place, namely—the exhibition space. It suggests, however, possibilities of movement and mobility within other spaces into which it may be relocated. A camera concealed in a Zeppelin-like balloon captures the viewers’ movements from above, and transforms this data into a dynamic line drawing projected on a two-way screen in the entrance to the space. Light beams emanating from moving floodlights installed on the floor search for the Zeppelin, and additional cameras attached to those lights document the various movements registered in the space. All this, including the movement of light beams and of the Zeppelin, is transmitted as data to a pair of printers which emit it simultaneously as one long paper loop. Throughout the show, a dense stratified drawing of all these occurrences forms on the paper loop, until the entire paper turns black and the data obfuscates itself.

The different forces at work in the space strive to capture, conceptualize, and visually interpret the “Now,” but that interpretation is distorted by the temporal gaps and multiple perspectives. This throbbing work responds to the time (speed) of light, the time of data transfer to the computerized system, and the time of the viewers’ lingering while moving through the space. The two-way screen welcoming the viewers at the entrance interprets the totality of movements at a given moment, projecting not only that, but also a register of movements from an accumulating memory reservoir.

We are confronted with a black box of art, a data base, or a laboratory equipped with surveillance cameras and satellites that call to mind contemporary spy movies in a world filled with means of control, a world in which information is gathered constantly and everywhere, and whose population is subject to the watchful eye of the “big brother.” The intrusive act elicits questions about authority and about disciplining the public space by technological means which have become a hidden partner in our lives, while penetrating every public space and generating virtual spaces which collapse into the lap of the real. Orb introduces a powerful world which conducts itself by the strength of self-sufficient existence, while playfully alluding to that which may get out of control, to the inhuman and the terrifying.

The screen courtesy of The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

The Fair of Earthly Delights is constructed as a ramified system of intertwined images extracted from diverse fields. Thus, for example, the great stormy wave curling over Japanese boats in Katsushika Hokusai’s iconic work, comes to resemble a “Nessie”-like octopus in Liav Mizrahi’s work, calling to mind the legendary monster from Loch Ness, Scotland, while in between the two the artist inserts image splinters taken from the arsenal of contemporary advertising and consumerist culture, crossing and manipulating them via digital processing of cut-and-paste-as-you-please.

For Mizrahi, the ocean is not only a mighty natural force and a route of commerce and migration (the sea is, apparently, a common cause of death among refugees who wander around the world, mainly those traveling between North Africa and Europe); it is also a space for conveying images which float together in a global-collective unconscious. Hierarchies are eliminated, times blend, and representations of East and West lose their distinctions. The circus-like strategies adopted for the work transform the viewers into an audience at a post-global vanity fair, into gamers in a role-playing mise en scène. The viewer is invited to stick his head into holes in life-size cardboard cutouts, in fact into a niche where the head of a refugee whose body was washed ashore once lay, except that the beach seems to have been drawn directly from Caspar David Friedrich’s romantic painting, Monk by the Sea.

Ocean Dome, Miyazaki, Japan is part of the famous series Small World by British photographer Martin Parr, who, throughout the 1980s and 1990s, pursued the accelerated developments in the culture of tourism. International travel and flights became routine at the time, and common folk could afford what was previously the exclusive perk of the wealthy. Mass tourism became yet another branch of the well-oiled distribution apparatus of popular culture, a culture which sustains an aggressive economy and flattens local cultural baggage, ridding it of its singularity.

Neither flattering nor compassionate, Parr’s lens reflects the tourists as a dumb mass flock, a violent swarm of locusts. At the same time, however, the ironic photographs in the series convey a melancholy over the lost ability to travel, to have an experience detached from purchasing power, lamenting the lost ability to become acquainted with an actual culture and not only with its synthetic superficial representations.

The video work The Line by artist duo Nina Fischer and Maroan el Sani addresses the identity of a structure emptied of its original use, inquiring how transparent material histories such as these may gain visibility.

Shot in a deserted, partly-demolished shipyard in the south of Denmark, the work is centered on one of the former employees who refuse to accept the conditions surrounding him. He ostensibly carries on with his daily routine, which is now reduced to drawing a line between the old shipyard and a new site for manufacturing wind turbines. As if possessed by spirits of obsession, the man attempts to complete a line across the industrial landscape, which he draws using a plethora of different means—a thread, a spray can, and a long rope tied to a boat sailing from the shipyard to the opposite bank. Learning that the rope hanging from the boat is tied to an anchor fixed to the shipyard bank, however, it becomes clear that this shipbuilder will never break free from the obsession and memory haunting him

The work laments the loss of identity, as well as other ailments that strike a community as it loses its primary source of income, especially when such a workplace is based on traditional industries and trades. It reminds us that the contemporary digital mode renders work processes transparent and invisible, dissociating them from their original context and from the economic system which renders their meaning. The video explores the resulting void while perusing deserted urban production spaces whose future is unclear and whose past echoes like a restless ghost.

The works of American filmmaker and artist Ryan Trecartin are usually multi-participant sculptural video installations. The first layer of each work is the textual—whether a poem, or a list of words which expands into a script. The narrative gradually dissolves, leaving only figures modeled as embodiments or markings of mental states.

In the process Trecartin collaborates with close friends, authorizing them to take creative responsibility, so that he does not have complete control or exclusivity over the nature and contents of the final product. His work thus becomes an unconscious reflection of youth culture, a refinement of the zeitgeist of a disturbed, anxiety-ridden consumerist society wallowing in spiritual nihilism. The accelerated, obsessive speech emitted by the participants, as if they were part of some cruel reality show or a radical Surrealist game of automatism, constitutes and loses meaning at the same time.

One may say that Trecartin is not interested in the content of the texts, but in the situation or frame in which they are uttered, in their speaker, and the state of mind they effectuate. In a world trampled under the wheels of globalization, the English language, he believes, is radically influenced by the capitalistic vocabulary: countless words have become “good” or “bad,” deteriorated, emptied, or expropriated by some corporation. His figures are refugees or reflections of that linguistic system in works which describe not a crisis, but rather systems after they have experienced a crash. This post-crisis globalization is also manifested in sexual identities, just as it reflects on ethnic identities. The figures operate in the gap between their beliefs or ruminations on the modus operandi of the world and the way it really works.

Comma Boat stars professional actors known from TV sitcoms, alongside others who participated in Trecartin’s previous works. The artist himself enacts a charlatan filmmaker who despises humanity and those who research and delve into its workings. In a space which is possibly a home, possibly a reality show studio, characters document themselves and are documented in verbose monologues addressing their identities, using exaggerated facial expressions and vocal distortions. Video is thus presented as a narcissist medium whose essence is the constant exploration of self representations and self reflections. Acting penetrates life so that despite the incessant engagement with shaping one’s self identity, an aggressive reproduction of forced identities from the outside is made manifest. These dynamics result from the processes of globalization and means of communication which disseminate these processes ubiquitously. Consumerist culture generates the fantasy of being an identical duplicate, mechanical reproduction takes over the realms of individual personality, and people transform into characters.

The spirit of João Delgado has been haunting Diego Rotman and Lea Mauas, members of the Jerusalem-based Sala-Manca Group, for fifteen years. A Portuguese poet, writer, playwright, and essayist, Delgado was, in all likelihood, born in Lisbon (date unknown) and disappeared in Argentina in the second half of the 1970s, in the dark years of the Generals’ regime. Like the circumstances of his disappearance, his life was equally shrouded in mystery, and little is known about it. Years later, his post-realist poetry has had a vast impact on late 20th century Latin-American literary avant-garde, but Delgado himself did not live to see it, since the political circumstances—the censorship placed by the military junta in Argentina—and his own choices interfered with the reception of his works by the public at large. His writing was confusing, and he often used fictive aliases which further blurred his identity. In literary terms, Delgado was a modernist who addressed the formal questions of writing (like Georges Perec and the Oulipo group): the author’s identity, the gap between the text and the world, and the illusions of fiction and reality. In this he joined other, more senior, contemporary modernists, from the Argentinean Jorge Luis Borges and Portuguese Fernando Pessoa to the Hungarian Lajos Kassák, whose Cubist poetry from the 1930s and 1940s had influenced Delgado when he lived in Central Europe.

The members of the Sala-Manca Group, in their joint work as artists, curators, and activists, often revisit Delgado’s figure, publishing translations of his work and incorporating excerpts from his unfinished plays into their performances. The return to Delgado, the eternal migrant who wandered until he disappeared, is linked with Rotman’s and Mauas’s personal immigration experiences and the need to discover new territories through language and the act of writing.

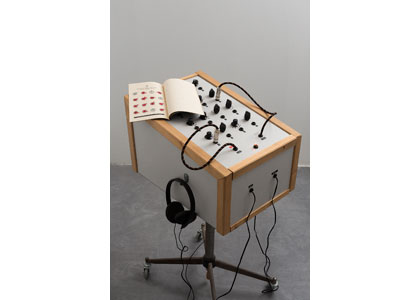

The work La Maquina de Hacer Pájaros (‘The Bird-Making Machine,’ as the name of an Argentinean rock band which formed in 1976, in the dictatorship days) is yet another chapter in the quest after the Portuguese-Argentinean writer. The viewer-listener is given the opportunity to wander amid excerpts of text by Delgado and other writers of his alleged circle, such as Juan Mestre, Regina Handeke, Irina Pantalova, and Arturo Maure, who may well have been none other than Delgado himself. This wandering is akin to a journey through the soundtrack of a literary microcosm, comprised of fragments of texts, sounds, and linguistic images. The listener is invited to try to compose the narrative as s/he pleases, to believe the story in whose making s/he took part, or disbelieve it altogether.

One of the legends associated with Delgado maintains that he made his way from Portugal to Argentina with the aid of a map of the Atlantic Ocean which he adopted from a Lewis Carroll book. Whether and how he arrived at his destination—no one knows. João Delgado is, in fact, a fictive entity, a figment of Rotman and Mauas’s imagination; at the same time, like them—who create in-between the splinters of their Latin-American and Israeli identities, in-between the language from there and the one they have adopted in Jerusalem—he is totally real.

The work of French artist Sophie Calle oscillates between writing, performance, photography, and cinema. At times she operates as a detective, unfolding her personal stories which are intertwined with those of others, mostly strangers.

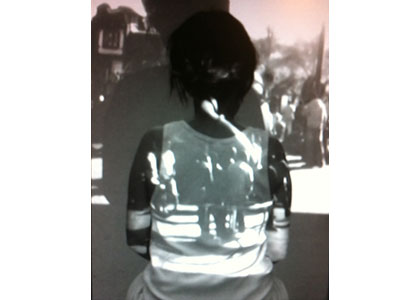

Voir la Mer was inspired by a stay in Istanbul as a guest artist. Calle read about the thousands of domestic migrants who arrive in the city from Eastern Anatolia for a life of overcrowding, poverty, and detachment, unable to afford a simple pleasure such as a short trip to the seaside surrounding Istanbul. She selected fifteen destitute people from the Kadiköy neighborhood on the Asian side of Istanbul, a quarter dubbed “the city of the blind,” because the Greeks who founded it in the 7th century BCE preferred it to areas bordering on the Bosphorus and the Golden Horn (the straits would have been a better and more natural choice, but the Greeks failed to see their beauty).

The participants, who never saw the sea, were taken by bus to the Black Sea north of the city, and were asked to walk the final 300 meters to the waterline with their eyes covered. “I told them to look at the sea as long as they wanted before turning to face me… I didn’t have any personal connection with these people. I just wanted to see their eyes—those eyes that just saw the sea.” They were filmed from behind in a manner which does not expose their great excitement to the lens. “The sea is something you can’t possibly imagine until you see it. Then when you do it’s overwhelming.” Initially viewers are called upon to imagine the facial expression of the person facing the sea, a grand powerful force of nature, which was only recently an unreachable object of yearning. When the subject turns to the camera and confronts us, his eyes reveal longing which only the sea can evoke.

The library at the Bialik-Rogozon Comprehensive School and the Lewinsky Park is intended for readers from Tel Aviv’s migrant worker community, whose lives in Israel are out of sight and out of mind, so to speak. The existence of this unique library at the heart of Tel Aviv, as a cultural island for a displaced community which leads a transient life, elicits thoughts about freedom in extreme situations, the place of art in society, and the relationship between hegemony and margins. Tali Navon’s work explores the mental and cultural processes undergone by a person reading, delving into the relationship between reader and text as a form of communication which influences the surroundings. In her “study,” however, she chooses to avoid the voyeuristic point of view on foreigners absorbed in reading, using her camera as a type of consciousness scanner which produces blurred, veiled images of a vibrant world amid the library walls.

Tamar Hirschfeld’s work flutters between continents and cultures in a funny, fanciful journey in which a white woman named Bianca (“white”) sets out to explore coveted, exotic realms in Africa. In continuation of the figure she assumed in her previous video installation, Schwartze Unveiled (2013)—a powerful cultural satire about the history of mankind—Hirschfeld in the role of Bianca now alludes to the great colonialist expeditions, and subsequently—to the figure of the white woman who ostensibly assimilates into the “primitive” black population, while being charmed by its incomprehensible magic.

Hirschfeld spent time with hunter-gatherer tribes in Africa, and her work refers, to some extent, to that of German filmmaker and photographer, Leni Riefenstahl, whose post-Nazi work depicted and studied the Sudanese Nuba tribe, in the spirit of the romantic journeys by artists-travelers prevalent mainly in the 19th century (such as Paul Gauguin’s voyage to Tahiti), which surrendered an “Orientalist” fascination with the artistic qualities of the wild landscapes and the “savages” living in them.

Hirschfeld creates near-impossible crosses in her work between different video excerpts documenting gatherings of people dancing in the fountain on Rabin Square in Tel Aviv—a leisurely, playful activity which calls to mind tribal rituals. The colorful banquet hall lighting illuminating a stalactite cave in one of the movies crashes into the primitive space of an exotic paradise when the tribal children are innocently tempted by Bianca’s grotesque attempts to communicate with them. With her fair hair and complexion, Bianca offers the “natives” myriad costumes; she makes them pose and smile for the camera, and even surrenders to the lens herself, but the result of this pendulous movement between cultures and spaces is fragmentary and does not yield a cohesive, unified narrative.

A model of a geometric staircase (which was indeed made of sesame imported from Africa for the making of tahini paste) is juxtaposed with the rest of the amorphous-raw objects inundating the work. These stairs possess an inkling of the oscillation between movement and stasis, and between humor and gravity, familiar from Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (1911), while also conjuring up the stairs designed by Michelangelo (1524) for the Laurentian Library in Florence; while the latter, however, lead to the spiritual assets of the Medici House, Hirschfeld’s stairs are a dead end, a climax-free final note that leads nowhere. These are stairs which question and mock stereotypical views regarding race and culture.