Natural History Museum

Curator: Revital Ben-Asher Peretz

02/04/2009 -

08/10/2009

The exhibition “Natural History Museum” sets up a simulated nature museum inside the Petach Tikva Museum of Art, in lieu of the absence of a national natural history museum in Israel. The featured works were created especially for the exhibition, the product of a two-year work process during which the artists carried out research and observations, accompanied by dialogue with scientists, zoologists, curators of natural history collections, entomologists, paleontologists, and taxidermists.

The exhibition borrows visual patterns and images from the natural history museum, “shifting” them into the world of art. Dimensions of reality are distorted via a change of material, scale, color, form, or medium: a mythological skeleton made of plastic chairs, a plasticine dinosaur, embryos knitted in wool, and a virtual whale. The totality of the works come together to form a mega-installation of sorts, in which each work represents and symbolizes a wing or a theme in the original natural history museum.

The exhibition strives to focus our attention on ecological concerns such as biodiversity, animal extinction, invasive species, the destruction of planet Earth, and man’s appropriation of nature. It examines the affinities between art and science, offering a commentarial, critical reference to the classical natural history museums in the United States and Europe, the majority of which were constructed in the colonial period. At the same time, the show addresses basic notions and dichotomies such as genuine and artificial, living and dead, positive and negative, the replicated and the preserved, the reconstructed and the duplicated.

Hilla Ben Ari, Yossi Ben Shoshan, Sidney Corcos, Avital Geva, Nechama Golan, Meirav Heiman, Shachar Kislev, Assi Meshullam, Uriel Miron, Roy Mordechay, Michal Rovner, Deganit Stern Schocken, Talya Tokatly, Itamar Yakhin, Zik Group.

Fleshy carcasses coexist with skeletons and bodies in different states of aggregation, all of them awaiting treatment, in the taxidermist’s workshop. In the museum’s back region, Assi Meshullam creates a staged platform which does not purport to be authentic, a spectacle typical of a natural history museum. By distancing one’s glance through a porthole (peepshow), the viewer witnesses an uncanny scene which seems to have been extracted from a horror movie: neglected skeletons, pieces of flesh, and mythical creatures.

Meshullam’s exhibits are sculpted in papier-mâché and plaster, drawing away from the “authentic model” customarily featured in natural history museums. At night, when the museum is closed to visitors, they shine miraculously in the dark, engulfing themselves with a mystical aura and sanctity.

In the taxidermist’s room brutal acts take place under the surface, appropriating nature, neutralizing it, and ultimately presenting it in a clinical, ordered, disciplined manner. Behind the cleanliness and order typifying museum display, ritualistic acts are performed: carcass gathering, cutting and burrowing in the flesh, skinning and bone cracking. The expressivity characterizing the aesthetics of the acts performed in the taxidermist’s fetid room is diametrically opposed to the civilized façade of Western culture, to the gaze it adopts on nature, and the story it recounts about “primitive” civilizations and wild settings.

In the taxidermist’s room the dirt remains in the back region, behind the scenes, far from the eyes of the “enlightened” audience taking the children to see a dead tiger.

In his work, artist Avital Geva combines science, art, nature, and life. The hothouse he set up in Kibbutz Ein Shemer in 1977 is underlain primarily by ecological research motivations. It is a place for interdisciplinary encounter; a “hothouse” for collaboration between plants and fish, zooplankton and newly hatched fry, between youth and scientists, between public figures and politicians, on the one hand, and artists and philosophers, on the other, and between people in general. The greenhouse, fed by water and moss, also “propagates” ideas and thoughts.

The algae pool was extracted from Geva’s Greenhouse (studio) as a type of readymade (found object), which annexes everyday life objects into the art world. The pool elicits questions about the interrelations between life and art. It was set up several months before the opening of the show, thereby creating a living work of art based on biological processes. These occur along a lengthy temporal axis, across three seasons. The active materials in this system fuse the technological with the organic: weather, rain, sun, wind, light, microorganisms, algae, water, plants, people, and mainly—time. The pool’s aesthetics is questionable. It does not exert itself to look beautiful. It generates green scum. Geva indeed creates a “staged platform,” a type of readymade frame, but the processes taking place in it are spontaneous, dominated by time and the elements.

Most museums of natural history have an open-air botanical garden on the premises. Man allocates a restricted area where it allows nature to “grow and erupt,” when, in fact, he prunes trees, mows the lawn, weeds and plants, creating a show of order and manicuring. Semantically, Geva’s pool is the “botanical garden” of the exhibition; an initiative of nature fenced in a plastic pool. Materials, energies, animals, and organisms which preserve part of the natural energy, pass through Geva’s systems.

Algae, as part of the food chain, develop and procreate, die and decompose. Reciprocity and symbiosis develop between constituent elements. The constant decomposition gives rise to invisible biological activities within the pool. The small fish eat the mosquito larva, which feed on the zooplankton, which is fed by the algae, which serves as food for bacteria in its decomposed form. One is dependent on the other, hence generating a cyclical process of interrelations between hunter and prey. Empowerment, growth, and expansion of communities result in radicalization and crises; an eco-culture of aggression. How does one regain reciprocity and balance?

Geva’s pool laboratory is a utopian, experimental, constantly-renewed place. The contemporary museum is likewise a place which strives for innovation and lab-oriented thought. The location of Geva’s pool in the unexpected context of the museum elicits contemplation about the human community in which we live.

The pool offers an ostensibly external reflection of the viewers, the museum building, and the trees. In fact, it is a reflection of silent, invisible processes at the core of human occurrences.

The deer is a recurrent image in Hilla Ben Ari’s works. Over the years she has sculpted its body and antlers in various materials. This time, Ben Ari has taken a “real” stag’s ear, a living-dead, taxidermied stump, and introduced a mechanical mechanism to it. By means of new technology Ben Ari creates a demonstration of the ear movement typical to some animal species, a near-negligent phenomenon occurring in nature, reserved to the animal kingdom. This repetitive, neural movement of a small organ generates a fidgety rhythm like ticking.

Separation of the organ from the animal’s body and its presentation as a dissociated stump joins the movement, detached from the other body movements, to produce a stumped action. A severed organ, a fragment, might elicit disgust, but Ben Ari’s deer ear is swathed in humor and irony.

Ben Ari has stepped into the shoes of the taxidermist, the scientist, and the curator of a natural history museum, who create a display with an added—educational, pedagogical—value. Observation is the common point of departure shared by the worlds of science and art: attention to, selection, exaltation, analysis and public exposure of detail. Ben Ari the artist opts for a tiny element: a single ear of two. She places it on the museum’s white wall, thus marking it as a work of art.

Itamar Yakhin knits imaginary animal embryos in typical “embryonic” postures; embryos in early stages of development: their heads are large, their bellies swelled, their arms short. He hand-knits, a work method ascribed to the realm of craft and associated with a feminine world, domestic, “low,” and anti-museal. Moreover, the choice of crochet, rather than casting or any other technique makes each product unique. Every creature is one-off; in scientific lingo, every embryo is a type specimen.

Yakhin has taken upon himself the role of maker, inseminator, the creator of “life,” and the role of scientist who gathers, preserves, classifies, and exhibits. The embryos are white and delicate. Despite their uniqueness, they are anonymous, even horrifying. The row of jars is full of imps, quaint little cryptids unknown to man.

Embryos have a relatively high hierarchical status in relation to the other reconstructed dead of the natural history museum. They are the thing itself: the skin, the internal organs, the tissues and tendons; preserved in formaldehyde in transparent jars; unfinished, helpless, incomplete creatures; “sketches,” temporary crosses whose life was cut short before birth. It is interesting to see a mounted lion from up close, but tenfold more interesting to expose a lion’s embryo which was concealed, hidden in its mother’s womb.

Thousands of jars containing human and animal embryos are usually stored in the cellars of collections and in research laboratories. Yakhin takes the collection of embryos preserved in alcohol out of the cellars, as it were, presenting them in the museum just as they were kept in the collection—on wooden shelves in an old display cabinet.

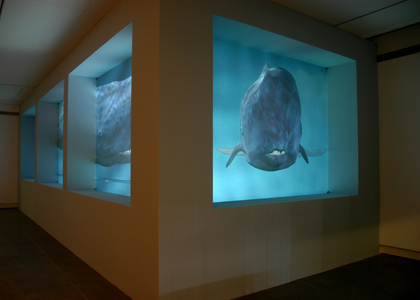

Every self-respecting museum of natural history has a whale or a Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton as a key exhibit, a major attraction. Meirav Heiman and Yossi Ben Shoshan’s sperm whale is threatening and at the wretched, miserable, and trapped, a “beast” transported from the exotic sea to an “enlightened, cultured” Western world. The fear arises that the whale might, in the twinkling of an eye, break the all-too-small aquarium. The water will then spill out onto the museum floor, and the whale will swallow its prey. Man feels small and frightened vis-à-vis the monumental mythological monster; at the same time, though, he also feels a sense of mastery and possessiveness, pride for having captured and vanquished the largest of mammals.

Heiman and Ben Shoshan’s sperm whale is kept in conditions of captivity: a small aquarium with turbid water. Only with great difficulty does it manage to perform limited movements. Walking around the aquarium, the viewer comes to know every millimeter of its body. The climax is the encounter with the mammal’s eye, which conveys empathy, despair, pain, distress, wisdom, sorrow, and a cry for help.

In Western culture, the sperm whale is usually thought of as a whale prototype. It appears in literary texts, paintings, animation, poems, and many other cultural works. Herman Melville’s renowned novel Moby Dick (1851) recounts the story of a whaling ship whose captain, Ahab, is obsessed with catching a white whale of tremendous size called Moby Dick, who took his leg on the previous whaling voyage. Even though the novel is primarily an intricate allegory, Melville, who himself sailed on a whaling ship for eighteen months, included in it a detailed description of life on whaling ships, the whale identification process, the chase and the capture. Another example is found in the story of Pinocchio, who is swallowed by a whale on one of his adventures.

The exhibits in natural history museums are always inanimate: taxidermies, skeletons, and bodies preserved in formaldehyde. The sperm whale in the exhibition, on the other hand, is an image of a living creature—a virtual whale, a product of computer work. With the marvels of technology, this image has taken a long way, to arrive at a level of representation so distant from the original. It is made of light and air, an illusion. Its existence is fragile and doubtful. Shutting off the electricity will cause this great spectacle to dissolve and disappear instantaneously.

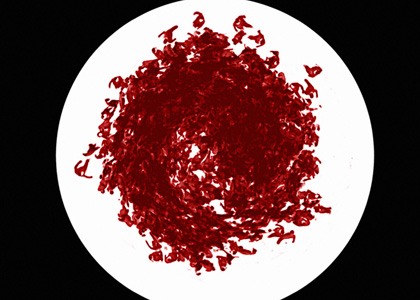

Michal Rovner quantifies human culture. “Culture #7” is part of the anthropological diversity, whereas “Cell Culture #7” is part of the biological diversity. Rovner offers an innovative, unexpected, unknown vantage point at the human creature. For Rovner, man’s existential-social foundation depends on the choice of point of view: Who are those lazing about, walking around, energetic yet purposeless? Who are those hurrying off, bumping, crashing, and virtually penetrating one another unheedingly? Who are those drawing into their bodies to the point that they become oblivious to their surroundings? Who are those running around on a round white planet, merging into movement, becoming a bustling, living flux as if within bleeding entrails? Whence have all these magical creatures emerged?

Rovner offers the viewer the position of a researching scientist, the one who asks questions and shatters conventions, observing from a high, critical, distanced vantage point. It is an experimental microcosmic observation of “human insects” with an identical, anonymous appearance. The scientist/viewer transforms the human figures into tiny germs under the microscope’s lens.

Analysis and exploration of social behavior in nature will maintain that the crushing/survivalist conduct of these creatures is clearly non-“cultural.” The observation has not yielded behavioral codes associated with connection, cooperation, consideration, compassion, or any other “human” relation. The observed creatures do not crowd, even though they appear to belong to the same species. The reported study results attest that they were forced into the same space, and they live their lives singularly, attempting to avoid contact and connection with each other. Thus they continue with repeated futile attempts, giving themselves to the rhythm and chain of cyclicality.

The life cell, the human laboratory, manages to exist in sterile conditions, in the lunar void, on the neutral surface conceived by Rovner. It is a celebration of eternity. In this Petri dish there is no apoptosis (death of cells as a normal part of an organism’s development), no cellular aging. There is only a set of cells which may grow infinitely.

Who do we observe condescendingly, as if we were observing earth from outer space? Who do we judge, criticize, and analyze? Who do we rudely penetrate and invade? Who are these primates? Who are these freakish hybrids? By means of a scientific-visual language, Rovner has created a mesmerizing show representing the cyclical, infinite life trajectory of the human creature.

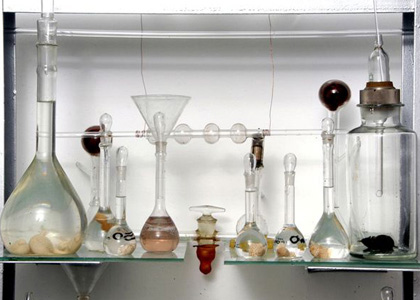

In a storeroom in the “Natural History Museum”, Nechama Golan established a laboratory for the creation of a golem, a human clone. A laboratory is a convenient place for the creation of myths and legends, where experimental processes which may threaten social conventions, norms, and taboos take place. All these are authorized by the scientific discipline as an “objective” category of knowledge justifying acts which violate directives of ethics and social justice.

Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Terminator 3 deals with omnipotent androids and cyborgs from the future, acting for the computer’s takeover of man. The film expresses the scientists’ fear of the continued effort toward the creation of computers’ artificial intelligence in light of an intelligent computer’s takeover of its human creators. The opponents of these experiments express the greatest fear of the “golem rising against its maker.” Since the future is always rooted in the past, the roots of modern fears of technology’s conquest may be found in ancient Jewish writings dating back to the Middle Ages, stories about the artificial man, the golem.

Golan’s work exposes the “back region” of the mystery lab to the viewers. She stages and creates the laboratory of the “mad scientist,” whose warped mind is teaming with ideas, and the materials around him—test tubes, bottles, jars, tissues, and blood—overflow due to congestion. Alternatively, this may be the studio of the “mad artist”: his ideas overflowing, his proficient hands overreaching, while canvases, paints, and brushes are scattered all over.

In Golan’s laboratory a human being is created as a golem. It is a theory extracted from the Jewish mystical practice, whereby Divine Creation is unparalleled. The Jewish golem is created from the most basic raw materials: mud, wind, and sand. Once it is created, the dumb golem is expected to “embody” a much needed role, yet it usually fails.

In nature, the pupa (golem) protects and conceals the insect lying therein. It undergoes a private, secret, enigmatic metamorphosis. When nature decides to emerge from the back region, it is beautiful and ripe after a period of dormancy, a transition time. Like the creature emerging from the chrysalis, the scientist too is hidden in his laboratory, seeking and researching, until he finally emerges into the world with an earth shattering discovery. Likewise, the artist shuts himself in the studio as inside a pupa, experimenting with various materials, until he finally shows his face in the exhibition.

In his works, Roy Mordechay often presents figures at the margins of society, “Hashlaglags,” as he calls them, whereby he discusses the notion of success in capitalist Western society. For the “Natural History Museum” Mordechay opted for a Hashlaglag from the animal kingdom—the Elaphrosaurus: “The Zionist Dinosaur.” It is presumably the only dinosaur to have regularly lived here. Neither impressively tall, nor a terrifying predator, it was a type of enlarged ostrich, a somewhat pathetic dinosaur. Mordechay’s Elaphrosaurus elicits a smile, invoking sympathy and identification. It is a type of autobiographical portrait with a dubious stature; a giant, grotesque and fetid mass of green substance. It buries its head in the museum floor, wallowing in a quagmire, publicly declaring its choice of blindness, of avoiding participation in the current era, and a search for alternative nature, one which exists underground.

Mordechay creates an anatomical imitation as faithful and realistic as possible of a dinosaur which became extinct millions of years ago. The clash between high and low is reinforced by the choice of material: plasticine—an inexpensive, popular, anti-artistic, non-ecological, toxic, synthetic material used by children, mainly for small, ephemeral works. Mordechay works with plasticine on a large scale, moving along the temporal axis from the Jurassic period, through the extinction of dinosaurs and the discovery of petrified relics, to the here-and-now.

The only evidence of the Elaphrosaurus’s existence is its footprint found in Beth Zayit. Mordechay’s work lures the viewer to press his finger into the plasticine. Making an imprint is a type of magic which enables changing the sculpture’s face and partially appropriating it. In an authentic museum of natural history it is forbidden and even scary to touch the exhibits. Contact with the grease from human skin might damage the taxidermies and skeletons; the animal furs are immersed in dangerous toxic solutions with chemical smells. Similarly, the exhibits in an art museum may not be touched either. In this case, due to the familiar, mundane plasticine, the sculpture becomes accessible for touch. Leaving a personal imprint through a touch of the finger is an expression of the human need to appropriate, destroy and intervene in nature (and art), much like the custom of carving names and dates on tree trunks.

By means of grotesque, oddball humor, Shachar Kislev, a cinematographer by profession, created the Feejee Mermaid in homage to the “authentic fakes,” the mythological mermaid, and the diorama. Her upper body is a stuffed Chimp, her lower body—a fish’s tail. A saccharine-sweet landscape painting is screened in the background: sun setting at sea. The female figure, the beautiful, virginal Lolita, who seduces innocent passersby, is, in fact, a hairy and repugnant stuffed Chimpanzee. She boasts a long mane, her young breasts protrude within a shell-bra, and her gaze is glazed. She sits on a rock, ruefully thoughtful.

Kislev’s Feejee Mermaid is installed within a “diorama,” a glass menagerie which is a prevalent display setting in museums of natural history. The diorama shuffles the customary taxonomic order as it combines flora and fauna from different places. It provides preservation conditions, including a controlled climate for the taxidermies displayed in it, offering an example of a zoological and ecological habitat. Hierarchical materials and combinations that never would have occurred to an artist today generate a surprisingly formal and colorful totality for the contemporary viewer: a combination of taxidermic animals, plastic vegetation, lattices, twigs, and trompe l’oeil painting.

Shachar Kislev: Three-Dimensional Binoculars

This work was constructed as a type of hyperrealist miniature diorama which generates an artificial setting. Within an interactive display device where the audience peeks through binoculars reflecting a world created by the artist, there are close-ups of quartz and precious stones and quartz taken from a museum of geology, in which the figures of scientists and of copulating couples were inserted. The binoculars simulate the “activity” wing of the “Natural History Museum.”

The miniscule objects within the binoculars become fantastical landscape sites, alluding to the 19th century romantic approach, whereby man was miniaturized vis-à-vis the natural elements. Kislev’s figures are within and at the heart of the landscape, yet they are tiny in relation to it, impressed by its inconceivable powers. At the same time, in Kislev’s binoculars man is a research scientist, setting out to control, comprehend, conquer, photograph, and thereby appropriate nature.

The mating couples are in the middle of an act which is the epitome of wild, instinctual, liberated nature, being exposed in the natural sphere. They are busy reproducing—the basic human instinct and the lofty evolutionary goal of life on earth.

Animals in nature have developed sophisticated mechanisms to ensure survival: the occurrence of matriphagy behavior in certain spiders (the offspring consume their mother so they may develop and continue the species); the head of a male praying mantis contains inhibitory neurons halting ejaculation, which, in turn, brings about his death. The female eats the male’s head to initiate copulation, thus causing ejaculation, which leads to impregnation and inevitably—to the death of the male.

Each of Kislev’s staged scenes takes place within a mysterious cave. The human beings imprisoned in it are likened to insects trapped in the binoculars. Each pair of binoculars exposes a section of a staged cinematic scene where we peek into the back region—backstage—to reveal the “bedroom.”

Sidney Corcos is director of the Natural History Museum, Jerusalem, and a professional taxidermist. In the exhibition he presents death masks and body casts, an integral part of his work as a taxidermist—the artisan of the natural history museum. These objects are made of raw materials also found in the studio of a contemporary sculptor or artist, such as plaster and fiberglass.

In the 19th century death masks were customarily made of a person’s face following death. The best-known mask is that of Napoleon Bonaparte. In order to make a death mask, a direct copy of the face is first created by smearing plaster on the animal’s face. When it hardens, the negative mold is extracted, and a positive mold is created therefrom. Body casting is made through a similar process, by means of polyester fibers and various polymers.

In the taxidermist’s studio one may find objects characterized by an authentic appearance and the freshness of an unstaged back region. Moustache bristles have clung to a lutra’s white death mask; the facial expression of a desert fox abashedly smiling has been frozen and preserved. The body casts bear various markings and numbers, which have become painterly, aesthetic graphic elements.

Corcos’s works vary in their definitions. Are they a part of a routine work process or rather—a work of art? The decision to present them in an art museum changes their initial context, raising them to the level of artworks.

Talya Tokatly’s pair of small showcases look like folding, mobile medieval altarpieces; crates in which mundane, ordinary, glamorless treasures with which the universe has endowed us, are kept. They do not contain groundbreaking scientific findings. These are residues and memories from the worlds of flora and fauna, which remain after the body’s desistence: bones, hair, nails, teeth; branches, twigs, and dried fruits, skulls, bird eggs, and maimed lizards—all of them hollow and eroded.

There are diverse taxonomies based on different logical orders. The child-like taxonomy, which is classified in a personal-emotional manner, is based on a logic of narrative and associative ordering: a child would place a pinecone that he found in his grandmother’s garden alongside a notebook given to him by his grandfather in his secret drawer; the taxonomy of the Wunderkammer (cabinet of curiosities), whose classification is presented according to identical groups of the same item (taxidermies, paintings, swords, maps, etc.), obeys the obsessive need to put everything on display; Linnaeus’s scientific taxonomy which distinguishes plants from animals, is performed for research. Tokatly’s private taxonomy is the artist’s taxonomy. It is a collection of findings devoid of concrete belonging in pre-classification state. Her small Wunderkammer obeys aesthetic-taxonomic values.

Tokatly does not loot an archaeological site. She sculpts the fragments, thus artistically distancing them from the original finds. Her objects, made from cast porcelain, are white and lime-like, as if they have calcified over the years. Tokatly’s “ancient” findings are invented, fake, and partly broken; they are fragile and delicate. They may be buried in the ground, unearthed in a future era, cast, buried, and so on. They are capable of generating an archaeological chain.

Tokatly’s natural collections are placed in a frame; a veneered frame and a museum frame. Does the frame lend them artistic validity? Can nature be reified? The boundaries between interior and exterior are blurred in this work. At times, the elements within the showcases are internal organs, and at others—a mere outer casing. Alongside the semi-exposed showcase Tokatly installs an open shelf in the spirit of the hands-on rooms found in many natural history museums, inviting visitors to touch. The exhibits in the showcase are not priceless and precious artworks, but rather plain, modest exhibits. Eggshells; a branch broken off a tree; a bitten fruit: these are particles of life that have withered and died, intended to serve as a reminder of the ephemerality of life and nature.

Uriel Miron’s cryptozoological skeleton is made of plastic chairs whose design has become an icon of Israeliness. Miron uses chair parts with multiple connections and bifurcations, sawing, isolating, and reassembling with wooden connective elements for cartilage. Like the scientific process in which a full skeleton is constructed from a single exposed fragment, Miron creates a fictional restoration by intuitive grafting and elaborating of the skeleton to the point of “total” imaginary reconstruction. Miron’s mythological skeleton is the Israeli cryptic: invented, made of an anti-ecological, non-expendable material—a “fossil” made from a modern material.

The Zik Group provides personal interpretation for recreation of the extinct ammonite fossil. The group, engaging in performance art for many years, will activate a machine on opening night that will scatter hot wax into a square, tar-coated pool where shiny black water is reflected. It is a dark fairytale type of pool. The machine, located at the center of the pool, is the heart of the ammonite. Wax is injected into the ammonite’s arteries by means of a long arm, wax which is akin to “white blood” breathing life into the fossil, a relic dead as dead can be. Like the way in which the original ammonite constructed its chambers, one by one, Zik creates the contemporary ammonite. The group revives a prehistoric creature whose form is approximated according to fossils and scientific hypotheses.

The performance imitates evolution in nature. Viewers are exposed to a secret artistic process of creation which usually takes place exclusively backstage, in the back region. The audience shares in a “bigger than life” moment in which “life is created,” and concurrently—the moment in which a work of art is created. In life, as in art, processes may be long-term and agonizing, while a birth may end in a few minutes.

Ammonite is a floor piece constructed inside the museum, forced on its floor as a field route taken from the world outside. Like a road whose pavement seals the ground and is forced upon the landscape, but ultimately becomes a part of it, its new “geology,” this work likewise generates a site, whose surface is coated with tar, foreign to the original language of the space. It is a site of contemporary archaeology made of contemporary materials. The performance is a show, the spectacle of the “Natural History Museum,” a spectacle coming from the activity wing. In this instance, the hands-on activity is complex, and is not permissible to the audience, therefore it becomes an “artistic act” performed by the Zik members, unlike the amateurish “hands-on activity” customarily held in natural history museums.

The collaboration between the natural elements and man—water, fire, gas, wood, metal, electricity, tar, wax, and the human hand—sustains the Zik’s Ammonite. Some of the materials are anti-ecologic and environmentally toxic. Man has become dependent on these materials to conquer areas and expropriate them from nature.

The Zik Ammonite sustains and embodies a symbiotic formal and conceptual system which identifies conflicts between man and nature; life, death, birth, creation, and human self-destruction. The Zik Group has been known over the years for burning its works. In Ammonite, creation defeats extinction.