Landsc®ape

Curator: Sigal Barkai

02/04/2009 -

26/07/2009

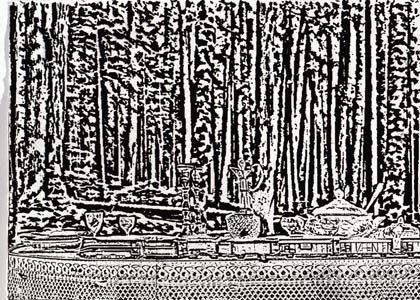

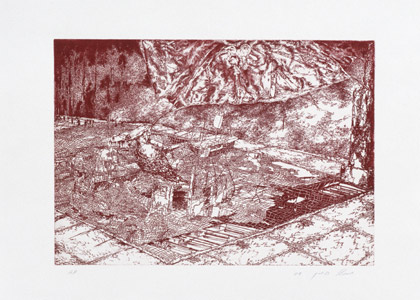

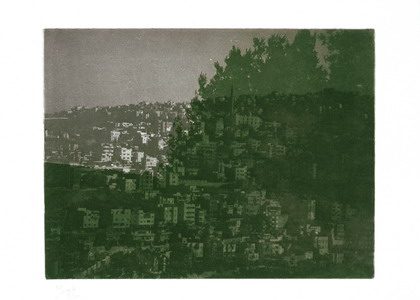

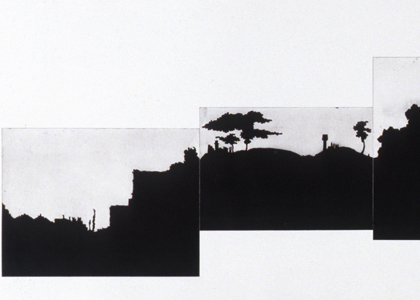

Landsc®ape:Representation Matrixes

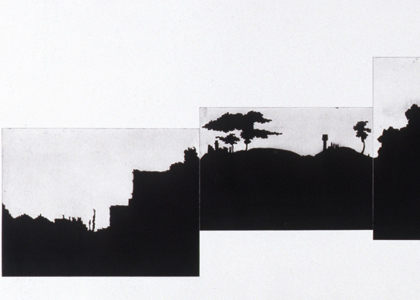

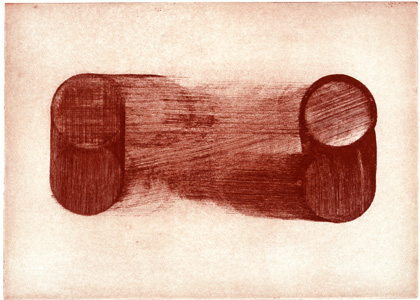

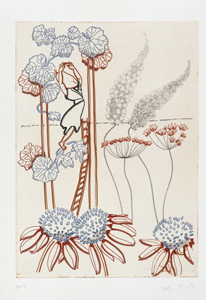

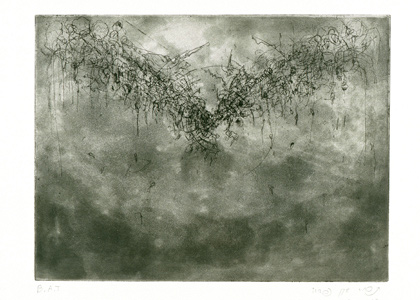

The exhibition “Landsc®ape” is the second in a series of shows linking the collection of Petach Tikva Museum of Art with a critical social view via etchings and prints by contemporary artists corresponding with the works in the collection. The artists’ exposure to the works in the collection was spawned by the desire to generate a multi-channel, inter-generational discussion of artists about the landscape. The artists invited to take part in the process passed through several stations on their way to creating the featured works. In the first phase they entered the collection storeroom, where they examined the range of landscape works created by the artists represented in the collection over the years. In the second phase, each artist selected several works with which to correspond directly. In the third phase the new etchings and prints were created at the Gottesman Etching Center, Kibbutz Cabri (Larry Abramson’s work was created at the Jerusalem Print Workshop).

The point of view of the collection artists, the real or imaginary place where the easel is positioned and wherefrom the landscape is seen, represents not only a physical place, but also an emotional and ideological position. The formative world views of the veteran artists in the collection have been nourished by Zionist thought in recent generations, since the early 20th century to the late 1970s. The contemporary artists, on the other hand—Jews and Arabs, men and women, young and old, newcomers and veterans—display diverse and stratified references to the landscape as an impression of a physical reality on a mental reality, and vice versa.

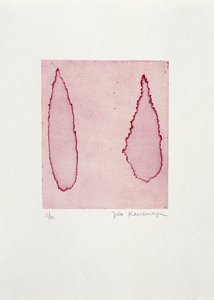

The landscape in the exhibition is represented as content oscillating between contradictory meanings: on the one hand, the Hebrew title Nof Hatoum (literally “sealed or stamped landscape”) attests to a formal, official approach. The registered sign ® in the English title, “Landsc®ape,” stands for a narrative fixed by a certain establishment, by a history told one way and not another; on the other hand—the landscape is sealed and treasured in the mind and soul of each artist, and is steeped in individual meanings. The trials and chronicles, wanderings, feelings, moods, sex, age, and ethnicity of each artist form a fine filter through which the meanings infiltrate and drop. The choice of the etching technique refers to the printing plate as a “stamp” which fixes and scorches a defined, uniform image, yet one which may, at the same time, be conceptually and technically manipulated, reflecting processes of transformation and personal interpretations. The artists work in the print workshop offered a range of possibilities for unusual use of the etching and engraving techniques in manners which deviate from the traditional modi operandi, thus expanding the boundaries of expression.

Jacob Steinhardt, Anna Ticho, Larry Abramson, Nurit David, Jacob Eisenscher, Hanna Farah – Kufar Birim, Hamutal Fishman, Erez Israeli, Yuri Kats, Sigalit Landau, Hila Lulu Lin, Manal Mahamid, Jan Rauchwerger, Tamar Shakin Pardo, Yochanan Simon.