Keeping at Distance: On Intimacy in Contemporary Painting

Curator: Liza Gershuni

14/03/2019 -

26/06/2019

“Seeing is keeping-at-distance”

– Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception

The artist is at the focal point, staring at the painting. The painting stares back at him.

Every painter is the first viewer of his own paintings, and every brush stroke on the painterly surface, every additional dab of color he applies, generates a new painterly situation. Behold! A new painting emerges in the place of the former painting, and the painter retreats, taking a few or many steps back—according to the dimensions of the work—to re-view the new painting, to observe it as a totality, stepping forward and back, time and again. To enable something in the painting, to change it, one must draw nearer—but then the painting cannot be seen in its entirety. To see it as a whole, to truly see it, one must step away from it—but then it is out of reach. This is the unique dance of painting.

Changing the physical distance vis-à-vis the painting also reflects other, less visible distance changes. The painter moves away from the painting along the temporal axis: he parts with it for a while, only to return with a “fresh eye” and rediscover it. He forgets it and remembers it, and most of all—he draws away from the painting on the inner, mental, emotional level: one moment he merges with the painting, and the next—he observes it critically, as if it had been painted by someone else. The painting as “I”, the painting as “Thou.”

This physical dance of the painter with the painting, whereby she approaches it to the point of near fusion (the eye, the hand, the brush, the paint, and the canvas become a continuum), and once again steps back and parts with it, conceals an incessant search for the “right distance.” If I am too close to my object of observation, I might identify with it, lose myself, be pulled into the whirlpool of over-proximity; if I am too far, I might become detached, indifferent, and alienated. The “right distance” is the distance of empathy. What the act of painting exemplifies, as a physical manifestation of this dynamic, is that this distance is never static. The point of empathy is not static; to the contrary: it is always in motion, forward and back. If one wishes to stay in tune with it, one must move with it.

The act of painting (like other art forms) is thus a never-ending exercise and practice of empathic movement. This is the great therapeutic value of painting as a praxis. The painter constitutes intricate I-Thou relations (in Buber’s sense) with the painting, and the “other” viewer, too—you, for instance, who are currently observing the paintings in this exhibition—takes part in the game. In fact, the viewers also reenact the painter’s movement (or, at least, that is what we should do if we wish to examine the paintings thoroughly), draw away from the painting and approach it, over and over again, one minute being swallowed up by it, one minute stretching the distance between us and it to the limit. Each of us, separately, is alone in front of the painting.

To paint means to face the painting alone. Therefore, painting always involves uncompromising intimacy. Observation of paintings, too, such as in an exhibition, true observation, means facing the painting alone, one on one. Only when we allow ourselves this intimacy—which is not an easy thing to do, and can sometimes be deterring or even threatening—can we “drown” in the painting as in the gaze of a lover. The painting looks back at us; with it we are immersed in the holy-of-holies of being, separately but together, alone but not in solitude.

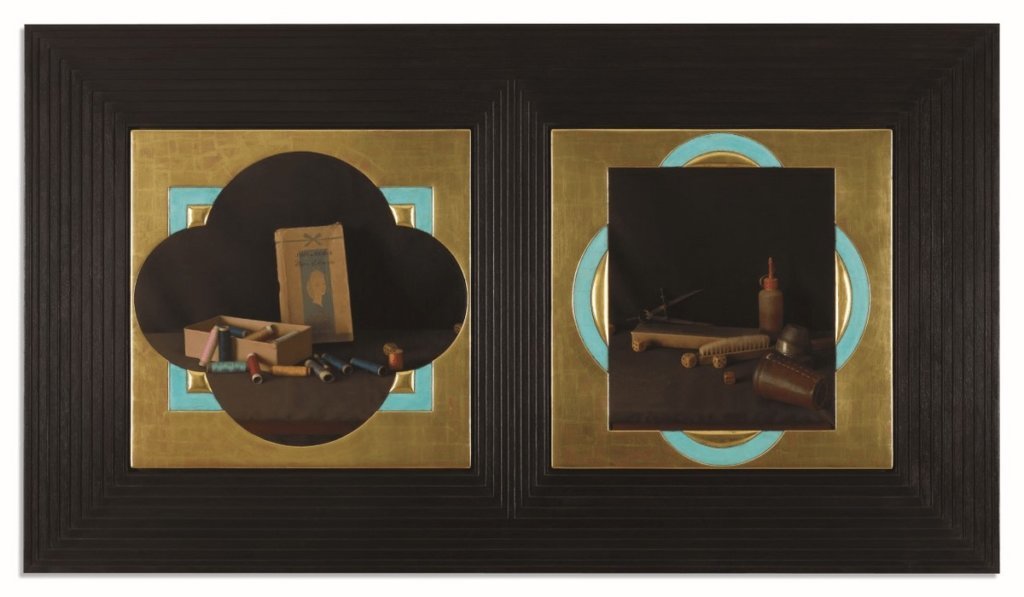

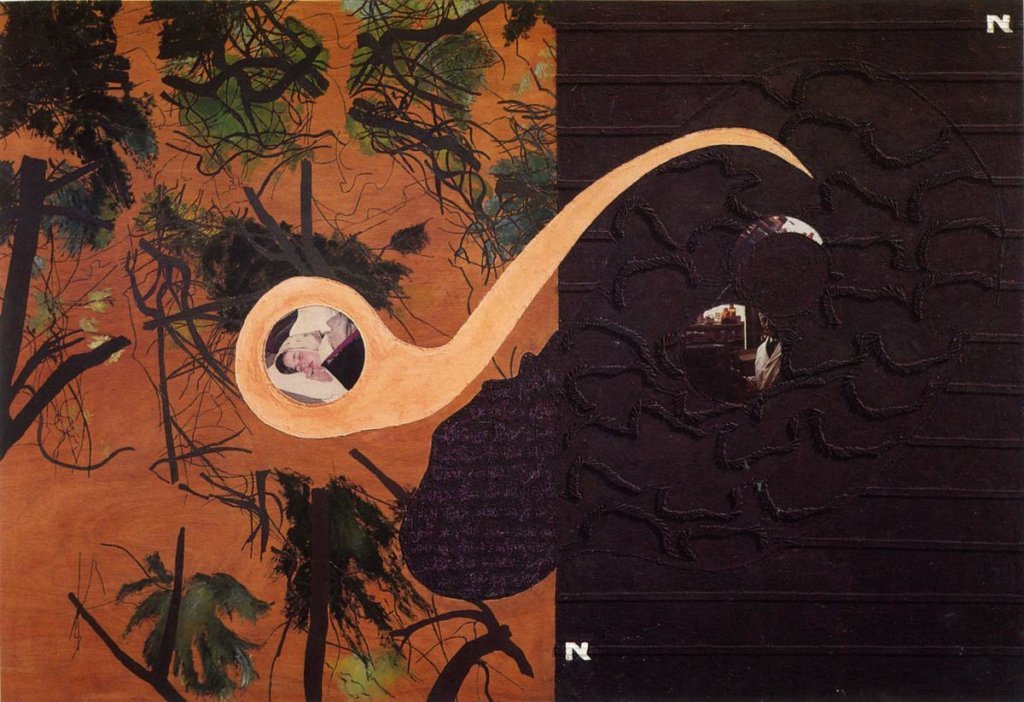

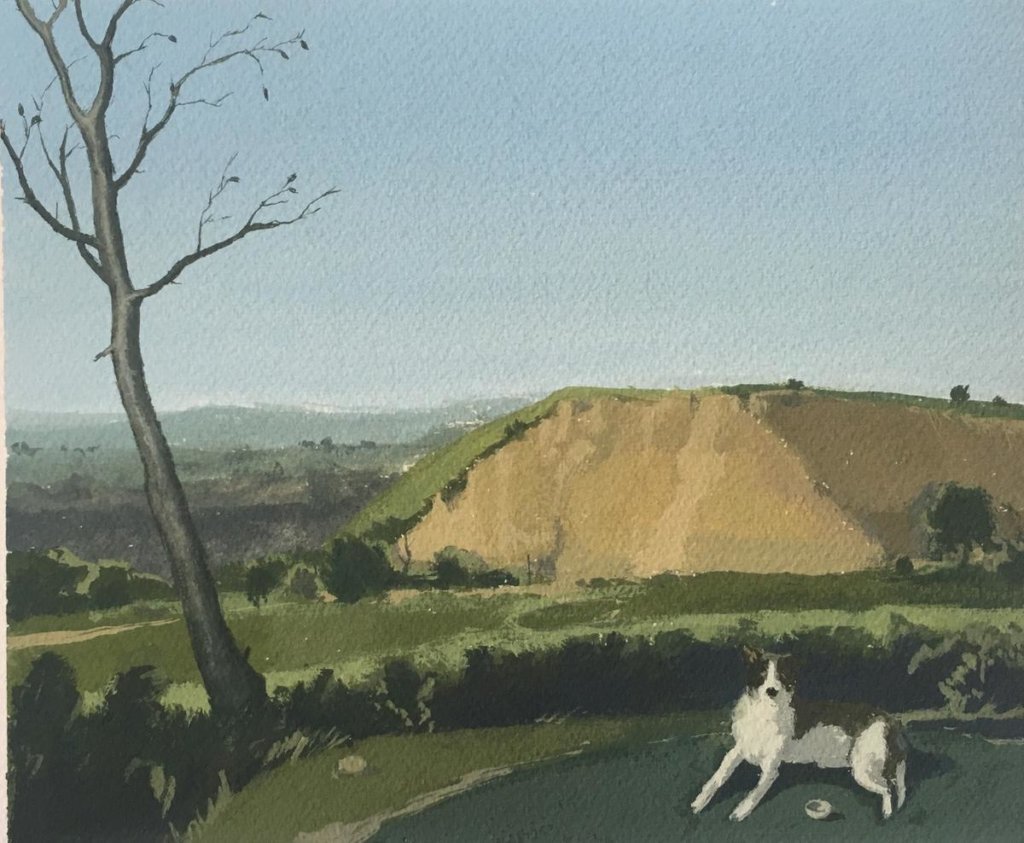

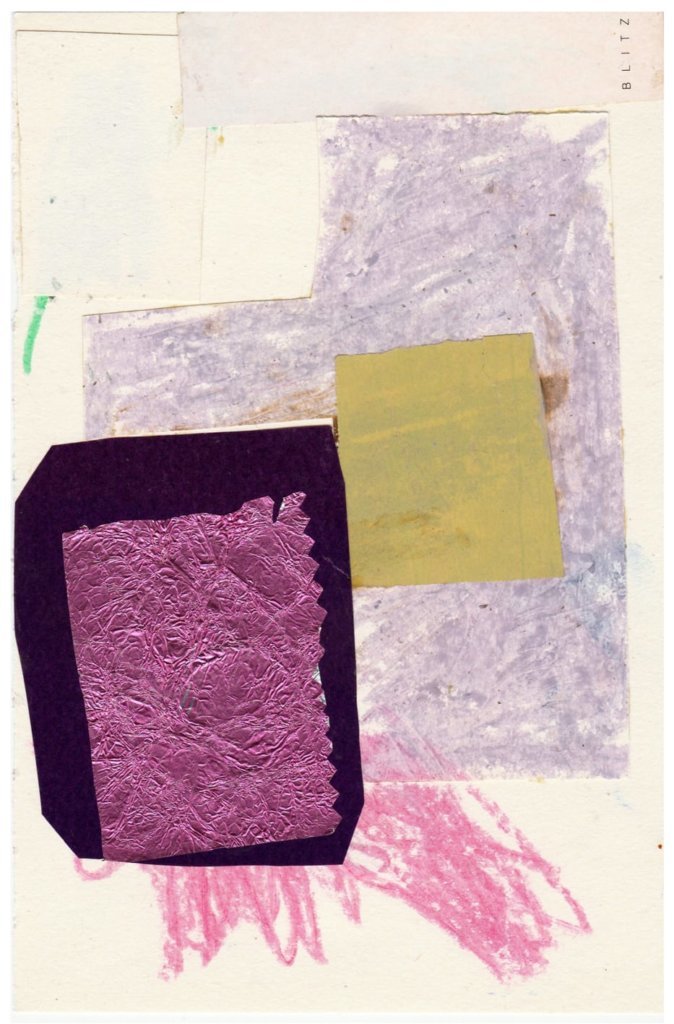

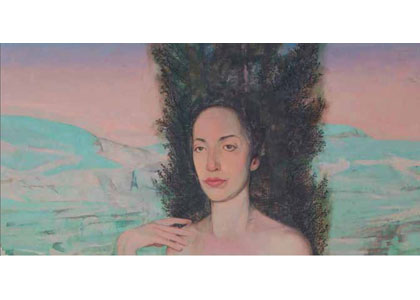

It is not easy to specify the criteria which guided the choice of painters for the exhibition (other than the obvious criterion of quality which always comes first), and it is not easy to find characteristics that apply to every participant, other than the simple fact that they all paint, namely apply color to some surface, and attempt, each in his/her own way, to apply the right color in the right place. The paintings in the exhibition represent something or nothing; they are either figurative or abstract, either spontaneous and impulsive or rational and calculated, or both; they are deeply rooted in the tradition of painting and feel at home in it, or struggle with it, rebel against it, and so on.

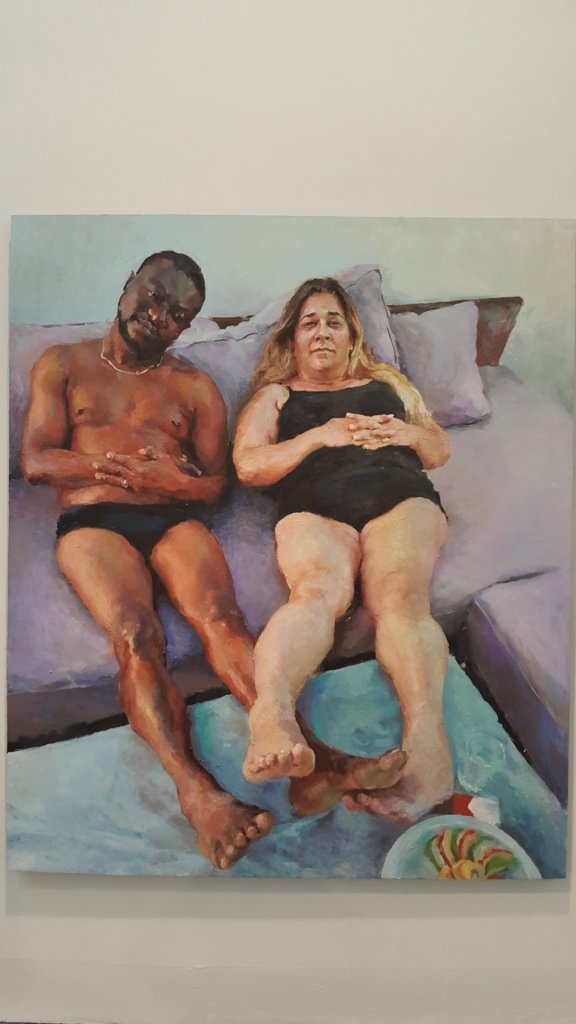

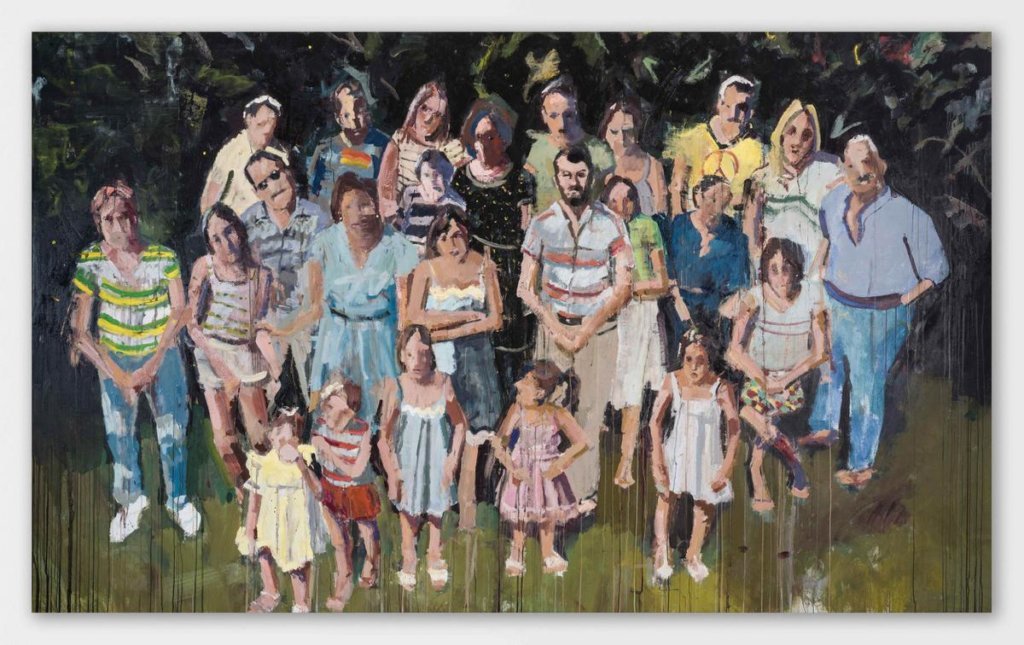

Still, there is a covert thread, an axis on which the exhibition is centered, and this axis is intimacy. Each of the featured paintings embodies an intimate, latent experience, at times highly specific, and yet always a basic experience of being-in-the-world, an experience of being which can only be conveyed by the painting (and even then, only if the viewer is open and attentive enough, namely inhabits a certain kind of intimacy with the painting while facing it).

Each of the paintings reveals a secret, of which the painter may not even be aware, and if she is, she would never be able to put it in words. “Behold,” the painting tells us, “this is what it’s like to be me in the world; this is what the world looks like through my eyes.” More than it sets out to decipher this mystery, the exhibition strives to respect it and give it room. The viewer stands and stares at the painting. The painting stares back.

Liza Gershuni