High Heels in the Sand

Curator: Revital Ben-Asher Peretz

08/09/2005 -

26/11/2005

Just before their high heels sink into the engulfing sand, they take off their shoes and replace them with soft sneakers. They make their way in the Sinai desert for days and days, most of them sick with the flu, but they may not sneeze or make any noise. This is how 3,000 women make their way every year to the promised land of Israel. They come from eastern Europe: Russia, Moldova, Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. From teenage girls to women in their thirties, most of them are mothers who need to feed their children and had been promised better working and living conditions. But from that moment on they begin to lose control of their lives, body and soul. They are sold as merchandise to the highest bidder and become part of the sex industry. Slave trade in the 21st century. In Israel the trade’s proportions are among the largest in the world. A prosperous industry with a turnover of a billion dollars a year.

It seems that the rank earth is ripe for action, for an act of art that would bring its strength once more into the social field. Undermining, in an almost militant act of visual defiance, the audience’s complacency. The exhibition “High Heels in the Sand” places on the agenda that which takes place in the country’s front yard – not the back yard, as many would like to believe. Art was enlisted, but life was the catalyst for action for every artist participating in this project, which was dubbed “the research”, laying out travel experiences from the past two year.

The basic values informing the curatorial work in “High Heels in the Sand” are a continuation of a line of action whose formulation has started in my previous steps as a curator: stimulating long-term group dynamics with the participants; work with creators who do not fit standard definitions of artists; and creating links between personal and social identity while examining the fine lines between society, culture and art.

Nine socially aware Israeli artists have turned into an active cluster after having attended a series of meetings over the past year, in which I shared with them details of my research on trafficking in women in Israel. They also listened to speakers specializing in the field, watched documentaries, and visited brothels and shelters for women. In addition, I worked with a group of women who are not artists, victims of trafficking residing in a shelter – a year of irresolute continuous activity, enabled by strength of will despite tragic circumstances. Some of the artists also worked in collaboration with women from the shelter.

The Research

Reading the horrifying statistics, journalistic and legal texts, psychology books and papers, and meeting with groups and organizations dealing with women trafficking, I became more and more aware of the intensity of the phenomena: Traffic in women is run by an intricate network of organized crime, across continents. The women’s legal status in Israel is that of illegal aliens. Having been bought by a pimp, at an average price of 8,000 dollars, they must pay the amount back by working it off. Most of them are held prisoners, beaten, often starved. Once in a while, the pimps decide to “freshen the merchandise”: they rent a coffee shop and run an auction, in which the women are re-sold to new brothels, new owners.

It is well known that there is a hierarchy within the Tel Aviv brothels. The old Central Bus Station is considered the inferior area. A daylight glimpse reveals wide-open doors and older, overweight women, their naked bodies only covered by torn shawls. The price of a woman here is five to twenty Shekels. The highest in the hierarchy of brothels are called apartments called “hideouts”, where young, pretty women stay. Each such brothel has a driver (guard, warder) who drives the women to clients. Each meeting costs about 200 Shekels. Each meeting is filled with fear and helplessness, and there’s no knowing how it will end.

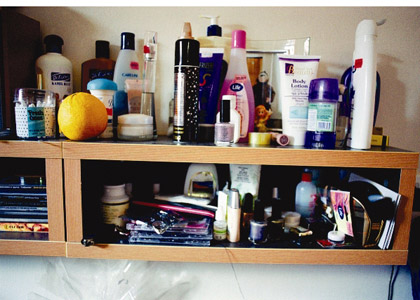

Near my home there is a brothel where imprisoned women are terribly abused. A long low structure made of exposed concrete, only the tight grid of a white iron grating on its windows indicates what’s inside. These are not meant to prevent forced entry, but rather to bar escape. The exterior alienation is replaced by a “warm” atmosphere inside. On the reception room walls there are illusionistic paintings of stone walls, from which decorative lanterns hang. Real velvet curtains compete with a trompe l’oeil rendering of red curtains, leading to a long corridor with doors that open to small rooms. On each door a numbered woman is painted. Inside each room there is a small mattress on a metal frame, red foul-smelling bed linen, and a shower. Some rooms are decorated with items such as a plastic ivy branch or ceramic reliefs. The women sleep and work in the same place. They are ordered to conceal personal clothes, objects, photos and cosmetics. The sense of personal female identity, already withered, dissolves. There is no corner one can escape to.

Works from the shelter

The Ma’agan (harbor) shelter for victims of trafficking is in the north of Tel Aviv, on the banks of the Yarkon river. The women it harbors had escaped from brothels or were released from them in police raids. They have agreed to testify against their pimps and traffickers, after which they are to be deported from Israel. This is where I conducted a weekly art workshop. A serious group of incredibly strong women was formed, full of passion for studying, growing and creating. The main obstacle to our work was the difficulty in maintaining continuity: women were deported back to their countries, some escaped the shelter, new women arrived, at times they were disheartened.

I never asked directly about their experiences as objects of trafficking and prostitution, but over time the complex autobiographic contents erupted like hot lava. Powerful, lively group dynamics transpired. Trust developed. Being “programmed” to please, to provide what’s required of them, they repeatedly asked what were my exact expectations. The type of work in an art class, the possibilities it opens up for the realization of fantasies, were a new experience. The women often dealt with hopes and dreams as opposed to their actual, uncertain lives.

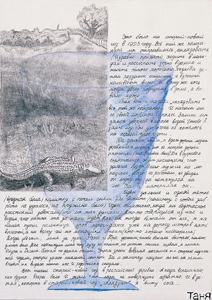

Tanya’s painting, Tanya and Rasmi, can be seen as exemplifying typical relationships of trafficking victims. Tanya, childish and small, claws the big Rasmi’s stomach with her fingers, in a desperate attempt to hold on or trying to wound. In other drawings, Tanya writes her memories on canvas, endowing typography with aesthetic value. For us, Israeli art consumers, the contents remain illegible. Tanya also created a clay rat. While working on it, she talked a lot about her “landlady”; by the end of the day the male rat was turned into a female one. Hybrids and cannibalistic rodents were a recurring element in the women’s works.

Lena Rudokova painted in Triptych an alienated environment, an arid desert on the cardboard packing of the parcels sent to her by her mother, a ghost town in three scenes with menacing overtones. She is only an actress making a guest appearance in a horror movie.

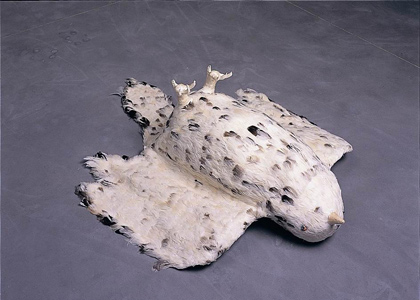

As in times of war throughout human history, these women, who are constantly ready to be on the move, had left their countries with a small bag containing a “survival kit” of sorts – a few photographs of home, the family, the kids, religious icons, some jewels. Ira chose a white toy bird out of a box full of personal items, and enlarged it to immense proportions. In Self Portrait, the beautiful, noble bird lies on its back like a huge cockroach twitching helplessly, borrowing the survival behavioral mode of animals that flip on their backs, pretending to be dead, in order to escape death.

In the shelter, a slow, careful process of nesting took place. Most women put together a small photo album, combining photographs from back home with photographs of themselves in Israeli landscapes – like admiring tourists. With equal wonder I looked at their photos of home: Lena, on her sixteenth birthday, doll-like, dressed in what looks like a fancy bridal gown; huge ornamental tapestries cover the house walls – for visual and practical warmth; dozens of furry animals lie on velveteen bed covers.

Part of the women’s store of images are also apparent in the works of the exhibiting artists: decorative elements, mice, dolls and animals such as rabbits or bears, shiny beads, makeup.

The Exhibition: Artists’ Works

Tamar Lamm’s photographic work, Souvenir, is a look into the only constant place (at the moment) in the lives of the women in the shelter. Lamm asked them to “stage” their beds for the photo and to place on it an item which they view as a souvenir, a relic. Salient elements in the photographs are childish, colorful bed-linen, floral or with heart patterns, angels and cosmetics. In the photo of Lena Rudokova’s room we note a common phenomena in the shelter – women joining their beds in order to sleep together; in Russia they were used to sleeping with their mother in the same bed until they became adults themselves. Lamm’s photographs are presented at the far end of white wooden boxes, set in cubicles that bring to mind Christian confession booths; the perspective creates an impression of an intimate peek into a miniature room, like a dollhouse.

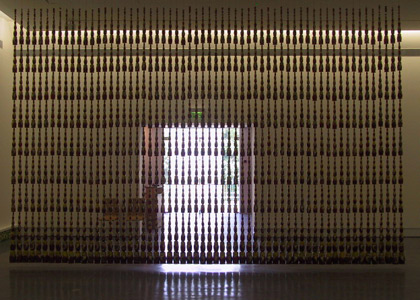

Yifat Gat, in the work 3,000 A Year, touches upon the act of commerce, importing 3,000 artifacts from Semionov, Russia, the town where in 1924 the first Matrioshka nesting doll was painted by a young girl. 3,000 – that is the inconceivable number of trafficked women smuggled into Israel each year. The Matrioshka embodies an archetype that is related “female craftsmanship”; the doll, an industrialized childish toy, expresses a primal, female desire for procreation. It brings the female act of reproduction to a grotesque, “industrialized” extreme – doll within doll within doll within doll… Endless containments and penetrations of girlish dolls. An ancient chronicle of women who are easily divided in two, turning into empty shells. Gat separates the dolls from each other and hangs each of them separately, endowing them with a new status of “wholeness” – closed and empty. Facing this enormous display of anonymity, a closer, more observant look is necessary in order to note each doll’s particular nuances: facial features, the eyes, a smile. The smaller the doll, the less details are painted on. Gone are the flower, the tie, the apron. On the smallest doll only a leaf remains. This hierarchy is also typical of the traffic in children, who are trained by older, more experienced “tutors”. The Matrioshkas are hung from strings, creating a colorful “bead curtain” – a common item in every brothel, semi-transparent, intriguing and inviting. But Gat’s curtain is almost fascistic in its dimensions, dwarfing the viewer.

Opposite the curtain, Gat installs the video Panda – a monumental (Russian) bear, inflated with air, full of nothingness. A small pin-prick would be enough to blow it up. It is part of a jumping facility for children in the center of Netanya. The photographed bear moves slowly forward and backward, a slow coital motion, like a parody of a porn film. Finally, the air runs out of the bear’s body and it withers and disappears.

Shula Covo advertises her phone number at large: “Have you seen how beautiful it is?” VIII – Try to seduce me. The phone number, part of the culture of modern courting rituals, is physically realized on the wall – drawn, printed, flat and curlicued, it gains presence, weight and beauty. This is not a number that can be thrown into the wastebasket like a used piece of paper. In Hebrew colloquial speech, conquest of a woman is called “a number”; Covo makes the number feminine. A hard-working woman, she embroiders the number with thousands of beads. The number is turned into magnificent pink jewelry. At first sight, the work captivates the viewer with its hypnotizing charm, and only then does one note the sorrow and wretchedness of the little “Christmas lights” that flicker in brothel doors.

For the women at the shelter a cellular phone is a treasured item, as it enables a sense of apparent security. But phone numbers are also a central means in the sex industry, and they are printed in ads in all types of media Covo, from a position of strength, challenges the man – “Try to seduce me”; but in displaying her real phone number, she also places herself in a vulnerable position, much like the women in the world of prostitution.

In the work Peep, Hilla Ben-Ari lays out an image of a large woman (Big Mama) on the floor, like roadkill thrown aside or like a crime scene outline; a dead body that has left behind only a vestige of a memory of a perforated, flat, two-dimensional body, composed of thousands of swarming, assaulting white mice. The mice devour the disappearing dead body, while also creating and sustaining it – it seems to be wearing a delicate, beautiful white lace dress. Her slightly spread legs welcome those who approach, and her wide-open arms bring to mind the furs of stuffed animals hung on walls, indicating male hunting skills, conquest, surrender and death.

Like Peep, the multiplicity of the modular craftsmanship in Ben-Ari’s Baseboard brings to mind carpets from eastern Europe: plenty of ornamentation and Uzbek coloring. The baseboard is a low, negligible architectonic element; only slightly raised from the floor, touching bottom. Its role is to absorb the dirt, so it doesn’t spread to the decent white wall. But baseboards are also contours, marking the room’s familiar, safe borderlines. The chain of existence is reversed in Ben-Ari’s work. It is the mice, parasitic animals, that rule – also by the sheer strength of numbers – and they suck on secretions from the women’s bodies (blood, milk), feeding on the very essence of vitality and femininity. The women are faceless, in crucified poses, martyrs. The mice tails penetrate the women through every possible orifice. Are they suffering, or giving themselves to the pleasures of the flesh? Is it the scene of a mass rape or a wild orgy?

Michal Shamir covers the walls of a room with candy that she irons and distorts into shapes of bleeding female organs, detached from the rest of the woman’s body and soul; pain, dissociation, wound. Dissociation plays an important role in the survival of trafficking victims. So do escapism and fantasy. The candy is a childhood delicacy, a longed-for taboo, sweetness that stimulates salivation, enticingly colored like the Grimm brothers’ menacing fairy tales, like the witch’s candy-house in Hansel and Gretel. Behind Shamir’s candy walls lurks the danger of becoming a victim to another person’s lust.

Video works are incorporated into the candy walls, presenting a flowing, liquid corporeality. In one of the videos, white, pure butterflies succeed in laying some eggs before dying, vomiting a staining substance; a short lifespan that only serves reproduction, starting with a beautiful butterfly and ending in red regurgitation. In another video, a thick white substance (hand lotion, milk, soap, semen?) slowly creeps along a thigh, viscous matter on bare skin.

The floor of this crammed, dense room is covered with an industrial, vulgar wall-to-wall carpet with food stains, leftovers in the shape of bunnies, bears and clowns. Human waste produces further layers of grime: mildew grows from the dirt, turning into abstract Rorschach blots. Shamir invites us into a room (a stale motel-room?) where the most intimate, discreet organs and acts are exposed through remnants of physiological human activities: food remnants, dirt, secretions, sweat and mold.

Meirav Heiman and Yossi Ben-Shoshan present a staged photograph, Backstage: women trafficking in Israel, class of 2005. The site is the make-up/waiting room for a TV talk show. A moment before going on air, the guests are attending to their appearance – are they properly made-up, are their outfits nice – and the issues that had brought them there are pushed aside. The photograph ostensibly documents a “backstage” scene, placing it on the stage. Heiman and Ben-Shoshan created stereotypes of “role players” in the world of women trafficking, who foster it and follow its rules: trafficked women, policemen, lawyers, judges, politicians, customers and traffickers; and the pimp shall lie down with the judge, the prostitute with the politician, the policeman with the john – and it isn’t always clear who is who. This breach of boundaries questions, of course, reality beyond the studio walls. In the dispute between reality and artistic narrative, the confusion is exacerbated: some of the photographed figures are professionals, lawyers as well as ex-pimps, who pretended in this production to be actors playing roles that correspond to their actual lives.

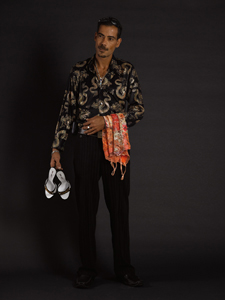

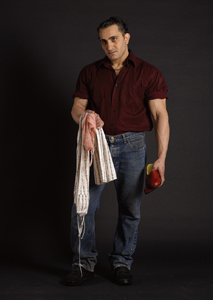

Also emphasizing the glorification of external beauty, a series of photographs portrays men holding female lingerie and shoes. They stand in line, as if straight out of a catalogue of Roman Caesars or a gay magazine, in masculine poses, advertising and displaying themselves, allowing the viewer to examine every wrinkle and muscle in their bodies. It is difficult to escape a judgmental viewpoint that stems from social classifications, definitions and categorizations. The female “present absence” is stressed vis-?-vis male corporeal presence. Even when holding a negligee and a soft bra, the male is in a position of power and the female image becomes wrinkled like satin-and-lace skin on his proffered hand. And yet, at the same time, he is presented like an inanimate clothes stand, and in some of the photos looks like a domesticated, at times pitiful, animal.

In the installation Get Lost, Heiman and Ben-Shoshan invite the active viewer into a long, dark corridor saturated with the mustiness of solitary confinement. A video is screened in the corner: the same social grouping from the group photo Backstage appears in A Birthday – presenting the celebration of an individual’s existence, a symbol of love and social acceptance, as a forced, pathetic gesture. The act of raising the celebrator on a chair turns violent, simulating a rhythmic coital movement that ends in the disappearance of the girl in the celebrating crowd.

The walk along the corridor is accompanied by sounds of a busy street. Slowly the place becomes clear: a basement, above which urban life runs; a sense of gutter-like suffocation and confinement. Through peep holes in the wall, the video “habitat” of a street section can be seen. A girl in a short mini-skirt walks unhurriedly back and forth. Her footsteps are hesitant, her feet convey bewilderment. The peeking audience is locked in the basement while she cruises the street freely. We witness the lower half of her body, practically looking into her panties, watching her covertly from below. The sense of excessive proximity to her body is both sensual and repulsive. There is doubt regarding her occupation; is every woman standing on a street corner to be suspected of prostitution? Standing in a specific place, in a particular pose, wearing revealing clothes, heavy make-up, perfume – are all these signs of prostitution? Questions dealing with the representation of the body on the uncertain boundary between fashion and prostitution recur in all of Heiman and Ben-Shoshan’s works, engaging in an intense dialogue between reality and its representation.

At the end of the corridor, the animated movie bordel is screened: movement, to the sound of a heavily walking man, along a dark corridor with sensually, temptingly textured walls, and entry into the mysteries of femininity – an enticing vagina dentata, a never-ending hellish torment.

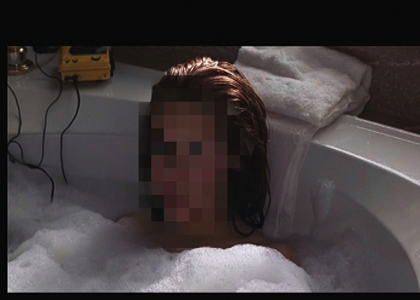

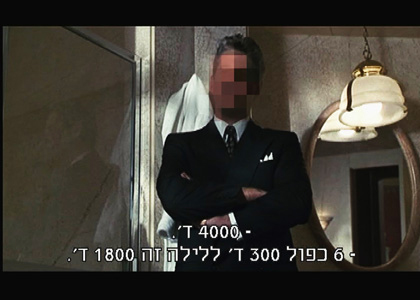

The pinnacle of the world of acting and “glamour” is Hollywood entertainment. Doron Solomons, in the video Solicitation, refers to a scene from a twentieth century fairy tale – the movie Pretty Woman; a Cinderella-prostitute myth. The movie is raised as an association in any discussion of prostitution and trafficking in women, and the trafficking victims themselves do not forego the fantasy, dreaming of a rich client who will fall in love with them and save them, with whom they will live happily ever after… Solomons deals with the scene of bargaining, the economic negotiations that take place when a woman is bought. He victimizes the victim, concealing the actress’s face and distorting her voice – a technique familiar from TV, used when interviewed persons do no wish to show their faces and be exposed. At times, these are the criminally accused, but often it is women, victims of sexual abuse or trafficking, who are driven by shame and fear to hide behind a screen of flickering pixels and an unnatural voice even when they dare to tell their story. The nature of the cinematic image changes from a romantic comedy to an action horror film, between feature and documentary. The new hybrid genre creates perplexity and pathos, resulting in painful humor.

And what about the actress herself, turned logo, who needs to survive in a male, sexual world filled with interviews, smiles and make-belief – is she also a victim?

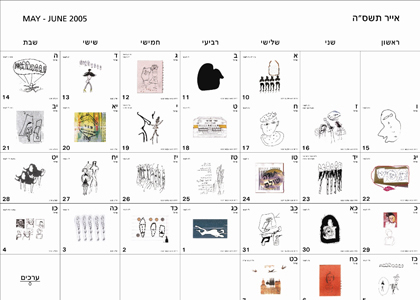

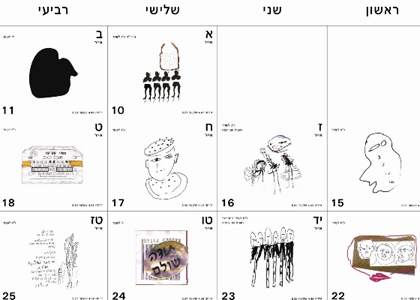

In brothels, the calendar serves as a work diary on which needed information is scribbled: shifts, work schedules and room allocation. Ita Gartner’s support in Work Schedule was an enlarged Hebrew calendar, focusing on the month of Iyar (May-June) 2005, during which there were several holidays: Lag BaOmer, Independence Day, Second Passover. Against this Jewish/Israeli backdrop, Gartner gives visual expression to each day of the month. The drawings depict pimps, johns, fragmented limbs, lips, lipstick, high heels, a Ukrainian passport, violence, fear, confusion, helplessness, blind herd participation, anonymity, exposure, shame, denseness, fantasy, discomfort, oppressiveness, body, illusion, compulsion, reproduction, withering, possession and emptiness.

Between the drawings a subtle interactive narrative develops, depicting emotional complexity. The computerized scan of the works is a manipulation of distancing and alienation; a manual touch of color at the end of the process restores personal, human warmth.

Epilogue

The works in the exhibition are informed by an inquiry into the analogies between trafficking in women and the fields of media and art, artists and viewers. Apparently, the artists’ personal acquaintance with the Ma’agan shelter and with victims of trafficking had affected their choice to address the issue from these aspects – a combination of emotional identification and a critical point of view, perceiving a variety of elements of trafficking and prostitution as present also in their own lives.

Trafficking in women thrives in Israel. At this very moment hundreds of women are crossing the Egyptian border, are locked up and raped. Some are deported to their countries of origin, and others replace them; fresh “merchandize”. The exhibition “High Heels in the Sand” seeks to remind us that these are women on the assembly line, and that each one is an entire world: Tanya’s charming smile, Ira’s ambitions, Marina’s child and Zhenia’s dreams. If we would only stop burying our heads in the sand, the heels could also break free of it