Citizens

Curator: Neta Gal-Azmon

06/04/2017 -

05/08/2017

In an attempt to restrain the natural human tendency and prevent people from abusing their power, modern democracies have formulated several basic principles to promote equality and reduce social injustice — including the separation of powers, majority rule (not at the expense of minority rights), freedom of the press, and so on. Today, it seems that these core values are being tested.

The exhibition “Citizens” was conceived in response to social inclinations currently challenging civil society in Israel and in other democracies in the free world. In view of the instability felt throughout the world, questions arise regarding the strength of present-day democracy and its ability to face cultural transformations and political upheavals. A stormy change of government in the USA, the rise of extremist regimes in the Middle East, the migration of millions who flee violence and destruction in their homelands — all these only reinforce the fear, uncertainty, and threat, further complicating the already complex democratic way of life.

The exhibition spans works by artists from Israel, USA, Spain, Italy, Canada, and Poland. These are read in the light of theories which already warned against the slippery slope from liberalism to totalitarianism in the 1950s. The participating artists ask questions about the innate tension between citizen’s rights and government authorities, shedding light on their points of collision. Through their works, the show explores the conflict between the state’s duty to protect itself and its citizens, and its counter duty to safeguard basic human rights, such as the freedom of association, the right to privacy, and the freedom of expression.

The exhibition features current reflections — at times critical, at others humorous — on notions such as totalitarian democracy, which embody the “paradox of freedom,” or the assumption that the realization of freedom entails the employment of coercive means and violence. Some of the featured works are centered on the Panopticon — the surveillance apparatus conceived by 18th century philosopher, Jeremy Bentham — and on Foucault’s interpretation of that concept, as a model for the anonymity of power in modern society and as an image of the individual’s internalization of the disciplining and signifying gaze.

New York’s Brooklyn Heights neighborhood has an especially high concentration of state institutions which inspire a particularly noticeable presence of “the state.” Wandering in its streets, one is exposed to the architectural idiosyncrasy of the neighborhood, whose streets are strewn with 18th- and 19th-century brownstone houses abounding with architectural gems. Due to its uniqueness, the neighborhood has been embraced by large production companies as a location for TV series and feature films. The Appellate Division Courthouse portrayed in Arnon Ben-David’s photographs, for instance, has served as backdrop for the TV series Boardwalk Empire and for Steven Spielberg’s film Bridge of Spies. “I was intrigued by the ability to shoot the government buildings while serving as set for a film, enabling me to address the tension between fiction and nonfiction as part of the political facet of my work,” Ben-David explains. His gaze projects questions regarding the status of government institutions in citizens’ lives on this stratified image: Do they activate our lives, explicitly or implicitly, or rather operate in the background, maintaining order?

Other than reality and fiction, Ben-David’s work addresses prevalent conventions, manners of speech, and means of production. Hence his decision to print earlier photographs using offset printing methods, and the ones in the current exhibition — on vinyl. It is rather the expensive, ostensibly higher-quality processes that indicate drawing away from the conventions familiar from everyday life. The use of attainable means is based on the realization that the uniqueness of the individual photograph does not lie in its objectness.

For over a month (from June 18 to July 23, 2011), in a period known as “the social protest,” Boaz Aharonovitch uploaded daily digital drawings to his Facebook page. The drawings were created after press photographs reporting demonstrations throughout the country. (The original drawings were recently supplemented by documentary drawings alluding to later articles in the press). Via an ostensibly laconic, yet lyrical, reporting style, Aharonovitch’s drawings depict harsh, charged, and violent encounters between policemen and demonstrators — grabbing, beating, arrests. Now their enlargements are being displayed on the wall, interwoven like a thicket which invests them with an intimate, near-erotic quality. The delicate contours on the black surface, despite the digital implementation, resemble street protest graffiti; the light summer clothes on the young protesters are juxtaposed with the rigid police uniform conveying power and control. The viewer is swept into the wandering motion vis-à-vis the piece on the wall, in an attempt to decipher what it portrays: a truncheon, a baseball cap, a horse’s head, a walkie-talkie, a cuffed protester — all these are revealed, emerging from a cryptograph, as it were. The density ofמthe meshed drawings is opposed to the lightness of each drawing as an individual image. Alongside the sense of chaos, this drawn tangle generates crowd power — strength resulting from the coming together of many individuals to pursue a common goal.

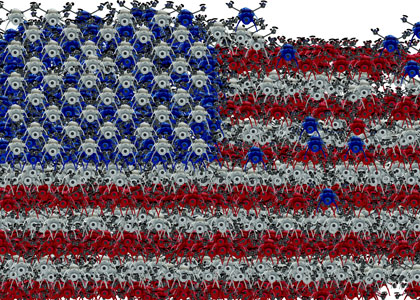

In this provocative self-reflexive video Cliff Evans assembles the flag of the United States from images of military drones, which appear toy- and child-like up to the moment they are identified as armaments. These sophisticated unmanned aircraft are used as a means of surveillance and attack. In Evans’s work, they hover in the air, seemingly awaiting an order, coming together and disassembling, intermittently constructing and deconstructing an image of the American flag.

In Flag, Evans — whose work is based (in his own words) on “stealing,” duplicating, and attaching Internet images to form a collage — cites an eponymous painting by Jasper Johns, one of the harbingers of American Pop art. Johns’s American flag appears, at first sight, like a banal copy; only a closer look reveals signs of criticism toward the consolidating national symbol. The stratified, creamy brush strokes and the newspaper clippings inserted in the painting place it in the 1950s, the years of McCarthyism and the early Cold War. For Johns and others in that period, the American flag represented not only the dramatic struggle between the Eastern and the Western blocs, but also the pernicious censorship, the infringement of the freedom of expression, the political and personal persecutions in the name of patriotism. Evans shifts Johns’s painted iconic flag to the technological medium, thus lending it an even greater subversive, perhaps somewhat paranoid, significance which reflects the socio-political situation in the beginning of the 21st century.

The point of departure for Cristina Lucas’s video is Eugène Delacroix’s famous painting, Liberty Leading the People, which depicts the July Revolution in France (1830) in allegorical terms. Lucas begins with an accurate reconstruction of the iconic image, which seemingly froze a heroic moment for eternity, fasting it forward by means of a state-of-the-art technological medium, to expose the continuation of the plot. Delacroix’s composition is centered on the figure of Marianne, the allegorical Liberty, who hoists the revolutionary tricolor flag representing Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity. As in history’s relay race, Lucas’s positions elaborate on Delacroix’s, discussing not only the virtues of the revolution, but also its ugly sides, its costs, and the dark side of liberty.

Delacroix, who advocated the values of the revolution, described the revolutionaries not only as bleeding heart idealists, but also as unrestrained mob that charges on while stepping on dead bodies on its way to victory. Lucas continues this by exposing a shocking occurrence: the mob from Delacroix’s painting, the one led by Liberty, turns its back on her, cruelly lynching her. The values of revolution and liberty, Lucas’s work implies, may be contrary to man’s nature, which is evil from his youth, threatening to surface when authority weakens.

A deserted parking lot hosts a discussion of weighty issues regarding human rights, the principle of ignorantia juris non excusat (ignorance of the law excuses not), sovereignty and proper public order, citizenstate relations, freedom of expression and protest, etc. Danielle Parsay, who arrived at the parking lot to perform an artistic act, unaware of its being illegal, found herself in a confrontation with the police which ended in detention. During the unexpected event she was forced to delve into her citizen rights and duties. The role of the representative of the law is assumed by a young Special Patrol Unit policewoman who likewise gropes her way through these concepts in an authoritative tone, as befitting the occasion. The two hold a stammering, rather entertaining dialogue, a fidgety dance revolving around topics which seem too heavy for both, while a “phone buddy” — probably the policewoman’s direct commander — enters the picture every now and then.

What started out as an artistic act, becomes a ludicrous, brave and purposeless defiance by a young artist who confronts the authorities in an attempt to bring basic civics concepts into sharper focus. The policewoman: “This place is a public area, but it belongs both to the municipality and to everyone… just an area, an area that is used.” Parsay is confused. Her question: “Who am I threatening?” remains unanswered. The policewoman: “Like, you came here to conquer the world?” With the announcement of the artist’s detention, the filming acquires the character of candid camera, a subversive act which renders the viewer an accessory to the offense. At some point, only background noise can be heard, since the camera is buried deep in the artist’s bag and the picture is blackened. Finally we get to see, for one jumpy moment, the metal floor of the patrol car and the bars, as an illustration of the officer’s words: “Welcome.

A football match, a demonstration, a coup d’etat, a nationalist show of force — all share a similar audiovisual aesthetics, stimulating fervent manifestations of group cohesion and power. The flag waving, the ecstatic masses, the rhythmic singing of the national anthem, the orchestrated motion in space, the homogeneity, the shared goal, the enemy defined as other — all these furnish the individual with a sense of power, belonging, and security.

The preamble to the American Constitution reads: “We, the people of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.” The individual defines himself by affiliation to a group which forms the basis for the generally accepted treaty — but this social cohesion might transform into a power trip by the masses, whose dangers have filled history books.

The football event featured in Eyal Segal’s La Rivoluzione — Italy’s loss to Spain in the UEFA European championship finals — may serve as a point of departure for contemplation of nationality. A straight line is drawn from the football stadium in Rome to the Colosseum, an emblem of the link between sports and politics, where gladiators traditionally fought. The same primordial instincts bubble under both fields: the same need to belong to a group, the same competitive urge to fight and win. The editing transitions between the game maneuvers seen from the audience’s point of view and their reflection-projection on the screen, between a sharp, clear image and a blurred shot, between light flashes and shadows, call to mind Plato’s Parable of the Cave. In this instance, the moral is that the ignorant masses perceive the reflections and echoes as reality incarnate.

In the summer of 2014 missiles fell on Tel Aviv. In those stormy days — during which neighbors, Jews and Arabs, crowded together in stairwells — someone set fire to a dumpster on the street in an act of protest. The chaos, the anxiety, the growing distress formed fertile ground for a spontaneous protest, which remained anonymous and thus refined, a protest for protest’s sake only. Inside the building — co-existence in the shadow of war; in the street — fire blazing, a small drama. In a neighborhood rife with contrasts, in the center of a city “with a past” of biblical and national, cultural and political myths, currently undergoing accelerated gentrification and gradually losing its fine balance in favor of “market forces” — a cry was heard, which was not formulated as a demand or a complaint, but remained raw and impulsive. In the light of the flames — a predesignated, age-old sign of civil uprising — the public sphere was experienced as a wrestling arena.

The work is named after the protagonist of Ray Bradbury’s book Fahrenheit 451 (the temperature at which paper burns, and, by extension — books are consumed by fire): a dystopian science-fiction novel unfolding a bleak vision of a futuristic social order under a totalitarian regime.

Federico Solmi conducts a grand, decadent ballroom dance with some of the best loved as well as most hated leaders in human history participating. Outstanding past leaders, identifiable in meticulous caricatures, are depicted by Solmi as foolish, Narcissistic, and arrogant. Ramses II, Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Genghis Khan, Napoleon Bonaparte, George Washington, Marie Antoinette, Benito Mussolini, Pope Benedict XVI, and other figures pop out of the pages of history, transpiring before us to the sound of an ongoing waltz at a banquet which is all self-gorging, gluttony, and excessive opulence. Capital holders, government, military, and religious leaders, fearlessly equipped with cigars and champagne, engage in dancing and what appears to be idle talk, while weaving among themselves a tangled net of international contacts that crosses continents and years. The grotesque is enhanced by the ludicrous attire, the medals, and the expensive-looking jewelry (purchased, or possibly received as gifts), as the viewer’s consciousness is flooded by a strong sense of incorrectness.

Solmi points a blaming finger not only at the leaders, but also at us — for the complacency, the blindness, the destructive tendency to perpetuate crooked self-myths. The video screen thus functions as a mirror, reflecting the danger inherent in the excessive trust we put in leaders back at us, urging us to observe them closely at all times. Because power — as we learn time and again — corrupts.

The notion of the artist’s signature — his “fingerprint” — acquires a poetic, and at the same time highly concrete, meaning in Gal Weinstein’s work. Weinstein burns his own fingerprint, outlined in cotton wool and attached to paper, projecting the act of burning in a loop as a continuous event. Observation of this ever-so-private physical trait going up in flames recalls another expression which encapsulates the artist’s relationship with his work, executed “with his last drop of blood.” This simple, well executed act seems to conceal great pain.

The fingerprint has become a metaphor for the individual’s singularity in light of the physiological fact that there are no two identical fingerprints. The unique ridge pattern on a person’s fingertips, determined during the fourth month of the fetus’s development, remains intact and unchangeable throughout one’s lifetime. Therefore, fingerprints are a primary means in identification, whether by the police or by security and intelligence organizations. Following 9/11, the American government has expanded the use of such biometric means for the purpose of the war on terror. In March 2008 the Biometric Database Law was also passed in Israel, requiring all citizens to give their fingerprints, to be combined, alongside a picture, in ID cards, digital passports, and a state database.

The law was approved despite extensive public criticism, and it remains controversial among ministers as well. The main fear is of an unrestricted infringement of citizens’ privacy under the guise of the law, use of biometric data without consent or knowledge of their owner, and expanding the use of the database for unintended purposes. The leakage of data from the Ministry of the Interior census to private hands and the Internet over the years, and the police’s impotence in dealing with the problem, raise the fear that the information might reach the wrong, or even hostile, hands. Furthermore, some argue that the law indicates a dangerous governmental state of mind, since the gathering of biometric details renders every citizen a guilty suspect until proven innocent.

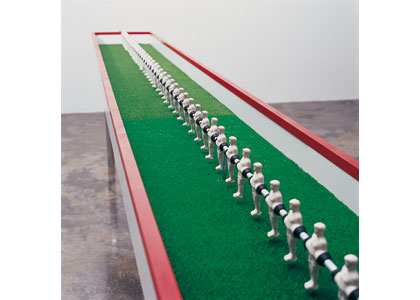

Gal Weinstein installs a line of identical porcelain dolls on a surface of synthetic turf. The porcelain figures are linked together with aluminum rods and are arranged in rows inside an elevated box-table (cabinet), as if it were a game of table soccer for two. A closer look reveals that these are castings of male figures, devoid of individual features. Hairdos and items of clothing are hinted: sneakers, socks, shorts, and a shirt. The porcelain soldiers are cuffed to one another, standing in a long line, looking ahead with impervious gazes, as if awaiting an order.

Unlike the familiar table game, the viewer is not invited to move the players at his will. Based on acquaintance with the game, however, it is clear to him that their motion — if such may be — will occur as a single unit, for a common goal, whose intensity and timing will be determined by the one controlling the field. While observing Anthem, thoughts about the power of the individual dominating the group, the power of the group which restricts the individual’s autonomy, the clear power relations between motivators and motivated, as well as notions of obedience and built-in conformism, cross the viewer’s mind. The opponent or enemy in this foosball match can only be imaginary, as well as the result of the confrontation with him. At present we are faced only with an alert glare, the calm before the storm.

In his site-specific installation, Gian Maria Tosatti examines the overt and covert functions of government institutions in our lives, their power and authority, and the ways in which they dominate the public sphere, human freedoms, and the right to privacy. Tosatti’s previous manipulations, performed in deserted spaces, are expanded here to the museum, which he transforms into a locus that is not readily decipherable, but rather calls the viewer for an investigation (in both senses), either as interrogator or as interrogated, as researcher or as researched. The investigation turns out to be both real-physical and conceptual. Like escape-room type of games, one may ostensibly find one’s way out of this space, and not only through the door in which he entered. The curious viewer (and accordingly — citizen), who does not submit to authority, will find that out. His inquisitive approach will lead him — concretely as well as metaphorically — into the depths of the apparatus. In fact, Tosatti changes the rules of the game, introducing the question of the gaze and its power in domination/subjugation relations, as the ostensibly enormous difference between viewer and viewed turns out to be fine and fluid.

In this context, Tosatti relates to the totalitarian regimes prevalent in post-WW1 Europe, to McCarthyism in 1950s USA, and the present right-wing trend. He cites Italian filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini, who noted that the most quintessential expression of totalitarianism is conformism, namely — the penetration of control over the individual from the streets and squares to the homes and families, even into the depths of one’s consciousness. We are all transparent agents of these forces, he maintains. Bertolt Brecht wrote in this context, while in exile, that poetry (and art in general) is the last defense, the most profound original language, on which the rudiments of our identity are founded. Art can set traps of disillusionment in the deepest layers of falsity.

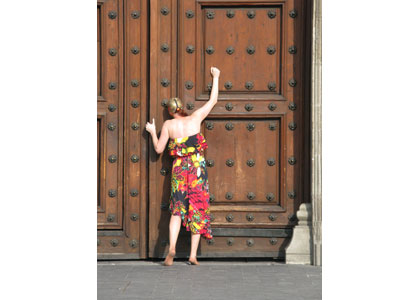

In 26 September 2014, 43 students who protested against the new government’s education reform were kidnapped in Mexico. Two weeks later their burnt bodies were found in a mass grave. An investigation revealed that police and government forces collaborated with major drug dealers to commit this terrible crime. Julia Kurek’s brave act of protest was performed in solidarity with the students and other protesters against the corrupt government, military and police in Mexico, organizations dominated by the large drug cartels.

Equipped with a mask supposed to protect her against identification by the various law enforcement bodies, Kurek is seen forcefully breaking through a police barrier, knocking barefooted on the heavy gates of the presidential palace. Unlike the mirror shield Perseus received from goddess Athena when he set out to fight Medusa, Kurek’s mask does not protect her from the monster she is trying to fight. In fact, it seems to put her at greater risk, eliciting objections by some of the audience to the event. As in gladiator fights, the audience is granted violent, passionate, life or death entertainment.

Kurek’s mask colors her protest with a theatrical, circus-like vein. Like the court jester — or a fearless super-heroine — she voices the citizens’ cry vis-à-vis the authorities’ corrupt indifference. Surprisingly, the audience of her one-woman protest is divided between cheering fans and booing foes who identify her foreignness (due to her golden hair), claiming that she insults government symbols. Kurek seems to throw herself at the mercy of the authorities as well as the masses in whose name she embarked on her action. Being a women, the cops are not allowed to touch her, so they try to prevent her motion by using their bodies to erect a human wall. Along with her, they move right and left in a comical dance, as she sets the direction and rhythm. Her provocative, colorful appearance is antithetical to their restrained manly uniforms. Although she fails in her mission to enter the palace, the calls of the crowd at the end of her act — Freedom! Freedom! Justice! Justice! — nevertheless attest to success.

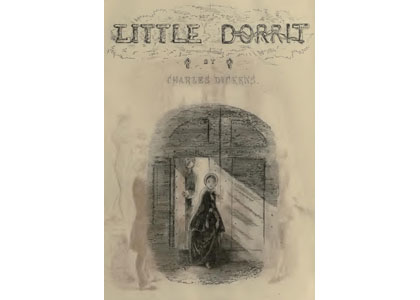

“The Circumlocution Office was (as everybody knows without being told) the most important Department under Government. No public business of any kind could possibly be done at any time without the acquiescence of the Circumlocution Office. Its finger was in the largest public pie, and in the smallest public tart. It was equally impossible to do the plainest right and to

undo the plainest wrong without the express authority of the Circumlocution Office. If another Gunpowder Plot had been discovered half an hour before the lighting of the match, nobody would have been justified in saving the parliament until there had been half a score of boards, half a bushel of minutes, several sacks of official memoranda, and a family-vault full of ungrammatical correspondence, on the part of the Circumlocution Office.”

The opening of the Kafkaesque chapter, “Containing the Whole Science of Government,” in Charles Dickens’s novel Little Dorrit (1855—57), offers an acute, satirical discussion of class, capital, and government. Mika Milgrom tried to read the chapter’s 17 pages to clerks and officials in various government ministries and offices, who unknowingly picked up the phone. The National Insurance Institute of Israel, Israel’s Income Tax Office, the Chief Rabbinate of Israel, Customs, the Jewish National Fund, the Ministry of Interior, the Standards Institute of Israel, the Ministry of Transport and Road Safety, the Tel Aviv-Jaffa Municipality, Israel Airports Authority, the Ministry of Construction and Housing, the Ministry of Justice, the Israel Patent Office, the Israeli Knesset, and the United States Embassy in Tel Aviv — were all harassed by her repeated phone calls, until she succeeded in reading each of them one page from the aforesaid chapter.

Knocking on closed doors with a defiant text addressing the impotence and smugness of fate-determining clerks who specialize in “sitting and doing nothing,” resulted in a role reversal, since the caller was not interested in conversion, a visa, an emigration permit, citizenship, or any other service, but rather protested out loud against the bureaucratic indifference and arbitrariness of the law.

The materials for this video were shot during the years following the 9/11 attacks. Nate Harrison, who lived close to the Twin Towers at the time, witnessed their collapse, as well as the dramatic and traumatic reincarnation of Ground Zero, first hand: from a landscape of elegant skyscrapers, to a disaster and rescue zone, to a scrap yard of molten metal cleared daily, to a gigantic hole gaped in the ground, and finally (until its rehabilitation) — to a dark-tourism attraction. As an artist and a citizen, Harrison felt a strong need to cry out, but the shock (or, perhaps, speechlessness) was too great. Art seemed futile and frivolous, he recalls. When he observed the tourists who arrived on site from all over the United States and the world, he noticed that they were photographing the empty space, the place where the Towers had been. “There was a mesmerizing beauty about it,” he attests, and he decided to perform a modest, personal, and poetic artistic act: to document these mundane moments of tourists who perpetuate the empty sky, that which is no longer, with home video cameras. One may regard this spontaneous civil act, which has become a social phenomenon, as an expression of the aspiration for universal cohesion, the human yearning to unite around symbols of absence.

In recent years Rafael Lozano-Hemmer has developed interactive technological installations intersecting architecture with performance. Using technological platforms, he invites the viewer to actively influence the work and take part in the artistic occurrence.

In Surface Tension, a large eye is projected on a “floating” screen installed in the middle of the space. The viewer approaching the screen activates sensors which make the eye open and start following his motion. The initial surprise is accompanied by a sense of playfulness. Being a solitary, dominant object in the space, the eye, however, is soon charged with additional meanings pertaining to the gaze — a key concern in art history which has frequently addressed the viewers’ gaze at the work of art and the gazes of the figures within the illusory artistic universe, among themselves and at the viewer. Reference to the gaze has changed over the course of history to reflect the zeitgeist, introducing philosophical, social, and cultural questions which leave their mark on art’s litmus paper. In this context, one may briefly mention Medusa’s petrifying gaze; Edouard Manet’s courtesan Olympia, who refuses to lower her glance, and with her defiant confrontational gaze annuls the objectifying male gaze; or the centrality of the eye image in Surrealism.

Lozano-Hemmer’s eye, in contrast, seems to lack any physical-environmental context, standing in its own right, floating in the physical space of the exhibition. It is a virtual-technological eye, ostensibly autonomous, which changes the familiar rules of the game by virtue of its interaction with the viewers. It seems to observe us more than we observe it. This game of glances calls forth pertinent questions regarding the power of the gaze in political and economic contexts of spatial domination: To what extent are we conscious of our being observed and documented in the public, physical as well as web-based sphere? Who is gathering data about us and to what ends? To what extent do we control our exposure to the “Big Brother,” even in spaces which we believe to be private?

Sasha Serber ties a large-scale acrylic-painted styrofoam sculpture, carved according to the best principles of classical sculpture, to popular culture. Its subject is the superhero Batman — also known as the “Dark Knight,” the “Caped Crusader,” and the “World’s Greatest Detective” — who first appeared in 1940s comic books. The juxtaposition of form and content gives rise to a hybrid creature incorporating the elitist glamor of Hellenistic art and the popularity of non-canonical genres, who, in the context of the current exhibition, is also charged with social and political contexts, both local and global.

Unlike other superheroes, Batman is an ordinary man who has taken the fight against arch-villains threatening humanity upon himself (due to childhood trauma). Rather than punishing the culprits himself, however, he hands them over to the police. Thus he is characterized as a fighter for justice and a law-abiding citizen. Via detective work aided by state-of-the-art technology, diverse martial arts, and uncompromising willpower, he does the impossible and repeatedly vanquishes the forces of evil. Much like Christian saints, Batman’s figure has undergone various transformations and distortions over the years; it thus succeeds in continuously meeting latent desires, by realizing every person’s childhood fantasy — the yearning for superpowers to protect him from all evil (and possibly also the aspiration to become a superhero in his own right).

Yael Frank’s video parodies the viral short films created by Walt Disney fans. The theme of national symbols — the national anthem in this case — is thought-provokingly juxtaposed with a radically different cultural field, while blending antithetical aspirations: the mature-serious-scarred and the young-naïve-optimistic. Blending the world of childhood and fantasy with the disillusioned adult world sheds a new light on the familiar, laying the dominant power structures bare. Alongside the estrangement resulting from the aforesaid juxtaposition, however, the work addresses the common denominators between these two worlds, as Walt Disney films, like national anthems, appeal to emotion, dream, and hope, presenting a utopia.

T.A.Z.: The Temporary Autonomous Zone is the title of an anarchist philosophical treatise by Hakim Bey (pseudonym) published in 1991, calling to set up temporary freedom zones to assist in the constant avoidance of government overreach. According to Bey, the liberation afforded by the anarchist revolution is short-lived and ephemeral in nature. To avoid falling into the trap of resistance and co-option (“If you can’t beat them, swallow them up”), he proposes an alternative tactic of disappearance — acting outside the state’s conceptual range in the form of “low” networked organizations within existing society. Highly democratic, egalitarian, liberal societies devoid of central governments, he maintains, have transpired in the past in areas outside the reach of state apparatuses. T.A.Z aims to create such transient mini-zones of freedom and autonomy, allowing for temporary escape from the state’s built-in coercion.

Ironically, of all things in Bey’s book, Zac Hacmon’s work with and in spaces adopts the “guard post” — an ugly makeshift structure that conveys anonymity, alienation, and control, but for the “guard” occupying it, it is an intimate, autonomous space. The work is based on the artist’s experiences from the time he worked as a security guard, and the guard’s booth offered him a microcosm of quiet in utter contrast to the definition of the job. Invited to step into the guard’s shoes, the viewer notices that a central element in this provisional structure is a CCTV that screens the goings-on in the museum space through the lenses of four security cameras. The booth, which offers the guard occupying it a refuge from the world, simultaneously defines him as an authoritative figure in relation to those outside it. Paradoxically, the T.A.Z becomes an aggressive means of territory demarcation and spatial control.

Zohar Gotesman’s monumental throne was inspired by 11th–13th century Romanesque sculpture. In contrast to Romanesque sculpture, which was closely related to architecture due to its decorative function, however, Gotesman’s sculpture has no structural function. It is not sculpted in stone, but rather made of glowing and quivering phosphorous rubber. Like Pygmalion in Greek mythology — the Cypriot king who carved a female figure in stone, fell in love with her, thus bringing her to life — Gotesman awakens his sculpture by means of a hidden mechanism. The tall chair begins to vibrate, as if it were a wild and independent, grotesque, gigantic dildo. The erotic Greek myth thus acquires a current interpretation with an exaggerated comic hue (“Everything is about sex. Except sex. Sex is about power,” as maintained by Frank Underwood, the arch-villain in the TV series House of Cards).

Gotesman’s throne tower also alludes to the biblical Tower of Babel — the story of pride and lust for power that led to the confusion of tongues and the birth of nationalism. The bitter end of that tower — like the foretold end of the giant erections effectuated by power, mastery, and authority — implies the end of the one occupying this metaphoric throne, because it is the base of the pyramid that determines its stability in the long run.