Agro-Art

Contemporary Agriculture in Israeli Art. Curator: Tali Tamir

19/02/2015 -

13/06/2015

Agro-Art explores the Israeli-Zionist agricultural ethos from the perspective of the 2000s, reflecting its changing status in recent decades. Israeli agriculture is measured not only in terms of landscape, food, and ecology; it is intricately and profoundly infused with ideology. Its being bound up with a redemptive aspect of a return to the body, to nature and labor, has provided it with the status of a formative ethos in Zionist rhetoric, while its appropriative territorial power and its being a major national tool of population dispersion into remote border areas, alongside its function as the supplier of fresh, quality food, has earned it a supportive state policy. Since the mid-1980s, however, the governmental perception that agriculture must be protected at all cost has gradually eroded in favor of the manipulative use of lands and a free market economy. The body of knowledge has been cut off from the land, agriculture abandoned the farmer, technological efficiency and the rising prices for water and labor reduced the number of people working in agriculture. Today, the agricultural produce is thriving, but many orchards have been transformed into residential neighborhoods; the tomato has replicated itself in a broad spectrum of hues and species, an emblem of technological sophistication, but the traditional farm is disappearing; the Israeli farmer, identified with historical agriculture, has ceased watering, given up picking, and bid farewell to his land, without a next generation to continue his enterprise. Together with him, a rich culture of knowledge, language, gestures, and actions departs the stage of history.

The twelve installations comprising the show range between an intimate-poetic statement rooted in personal memory and an agricultural agenda, and a socio-political attempt to analyze the power mechanisms at work in the agricultural arena, in the Israeli and the Israeli-Palestinian spheres. The field, the greenhouse, the neglected orchard, real-estate land, vineyards and olive groves—all stand out as charged sites. The cosmic tension between heaven and earth, and between rain and drought, becomes clear vis-à-vis the aging figure of the farmer, and next to him—his successor, the foreign Thai worker. Agriculture emerges as a gene pool of survival awaiting the time to act, and as an active agent of land appropriation in the Occupied Territories. From another direction, it is revealed to be an original, resourceful field of research. The “archive” accompanying the exhibition sheds a fleeting light on the nucleus of the original ethos from the state’s first decade, exposing the return of agriculture to the focus of attention of several avant-garde artists in the 1970s. Sisyphean and rife with danger like agriculture, art identifies these transformations and asks questions.

With the Support of The Jacob and Malka Goldfarb Family Charitable Foundation, Inc

Thanks to Bio-Bee Biological Systems Ltd.

for the assistance in implementing the project

In 1972 Avital Geva harnessed his students at Givat Haviva Seminar to a disk-cultivator and sent them to cultivate 1,000 sq.m. per day. In the 1980s, when he developed the model of the greenhouse in Kibbutz Ein Shemer and invited youth to experiment and explore ecological issues, the Gordian knot was already tied: for Geva, agriculture and pedagogy are intertwined, and both acquire their validity within the community. Agriculture, according to Geva, is not an assembly line of profit and loss, but rather an arena for development of thought and collaboration. Art is nourished by these integrated systems.

Based on a live broadcast from a beehive in Kibbutz Ein Shemer’s Ecological Greenhouse to the space of Petach Tikva Museum of Art, as the beehive is ostensibly being duplicated in a pool, The Bee, the Queen, and the Queendom addresses communal life, agrarian labor, and the productive power of the group. A community of earth bumblebees (Bombus terrestris) works in the beehive, entrusted with the natural pollination of the tomatoes growing in closed greenhouses. The pollination by bees contributes to increased crop yields, resulting in agricultural produce free of chemical spray residues. The earth bumblebee represents smart agriculture, which, in addition to being scientific, is also conscious of the consumer’s needs and the future of the planet. The greenhouse in Kibbutz Ein Shemer, in collaboration with Bio-Bee Biological Systems Ltd., is involved in research examining the behavioral patterns of the bee community in relation to pollen changes. Another study taking place on site explores the influence of the queen bee’s condition and the length of her hibernation on the lives of the bees in her colony.

Ayelet Zohar’s video follows the unheeded, faded and dusty vegetation along the sides of the Ramla-Lod Road (Route 40) and its surroundings at a walking pace, exposing the continuous, tenacious presence of the sabra plant, which served as a border marker for the area’s orchards in the past. “To place a plant within a historical context,” writes Marco Scotini, curator of the 2014 exhibition “Vegetation as a Political Agent” at PAV (Parco d’Arte Vivente), Turin, “means to consider not only its biological constitution, but also the social and political factors, which see it already positioned at the center of the earliest forms of economic globalization.” The Italian show endeavored to shed light on different situations in history in which vegetation functioned as a symbol of social emancipation or subordination. Unlike coffee beans or cotton, however, the sabra hedge does not represent subjection and slavery, but rather erasure and occupation.

Zohar’s film, which fluctuates between dumps, paths, and deserted buildings, links segments into a monotonous, stubborn, peak-free line. The frame dropping technique, which edits the film at 5 frames per second (instead of 24 fps), highlights the fragmentation, blurring, and discontinuity. The film thus becomes a metonymy of the deconstructed, disintegrating sabra hedges, a fragmentary, barren space, like the landscape it presents. Zohar’s walking gesture metaphorically reinstates the lost sequence of Palestinian orchards and citrus groves which disappeared after 1948.

Thanks: Dror Etkes (Kerem Navot), Yael Prolow

The wall piece Key is based on the disciplines of cartography, geography, and military or civilian aerial photography for intelligence, planning, and surveillance purposes. Dana Yoeli uses aerial photographs produced by Google, which are available to all, to reconstruct a one-day journey held in October 2014, following Jewish agriculture in the Occupied Territories south of Bethlehem. Yoeli combines a distant aerial view, which offers a vast, anonymous and abstract, sublime space, with a specific gaze that clings to the ground, where it identifies signs and traces of action.

Jewish agriculture in the Occupied Territories strives to realize a biblical vision by planting crops belonging to the seven species, as mentioned in Deuteronomy 8: 7-8: “For the Lord thy God bringeth thee into a good land […] A land of wheat, and barley, and vines, and fig trees, and pomegranates; a land of oil olive, and honey.” These crops (the honey stands for dates), considered fruits with which “the Land of Israel was blessed”, receive preferential status from the Jewish farmer in the Territories, who exerts himself to make their presence felt in the area and establish a fait accompli, pushing Palestinian agriculture out. Since devout Muslims abstain from drinking wine, the wine grapes have become a distinctive feature of Jewish agriculture in the Occupied Territories.

Yoeli lays bare the deceptive use of agriculture as a tool for creeping annexation of the Territories, evading public attention under the guise of a pastoral terrain. She isolated an aerial sphere, pinpointing several levels of signification and distortion within it: a settlement that has expanded the borders of its cultivated land beyond the agreed area, thereby doubling and solidifying its territory. Another area bears eight image sequences which together define a cartographic legend, or key, of agricultural actions carried out by Jewish farmers: marking the borders of a field; laying an irrigation pipe; razing boulders to pave a road; the traces of agricultural machinery in the sand; a barrier against wild boar roaming in the area; wastewater discharge; and more visible, clear signs, such as commemoration plaques, fences, and planting.

The parallel languages of agricultural presence attest to the dialectics underlying the Israeli-Zionist-settler culture: while deeming the Arab fellah an agent of biblical memory, who preserves ancient agricultural traditions, it simultaneously pushes him out and restricts his actions. By the same token, the olive tree, which is uprooted and moved around, has become the victim of the symbolic baggage with which it was charged by both cultures.

Following a frost that struck Israel in February 1973, the Ministry of Agriculture ordered the destruction of the damaged fruit. Dov Or Ner, who had worked in the kibbutz citrus groves at the time, loaded the marked fruit on a truck, scattered it on a piece of land on the kibbutz outskirts, and plowed the rotting fruit into the ground, to fertilize it in preparation for planting grass. This act demonstrated an organic process of recycling or reuse, while raising questions about the risk built into the agriculture profession, and the interrelations between agriculture, economy, and bureaucracy. Twenty-five of the faulty oranges were packed in plastic containers and mailed from the Hatzor post office to various artists locally and internationally. In the accompanying letter Or Ner asked his addressees to follow the orange’s rotting until its ultimate decay, and to add a personal response in the medium of their choice, referring to the physical processes they underwent during the period in which the orange was in their possession. The agricultural point of departure gave rise to a psycho-physical discussion.

In an era of “room agriculture” and “guerrilla gardening”—which have given rise to a new “civilian” type of a city dweller who grows his own food at home, thereby cutting middleman and transport costs, enjoys maximum freshness, and avoids unwanted chemicals—Gal Weinstein proposes moldy “studio agriculture” of an artist who is locked up in his bubble, imagining a “landscape” in black coffee grounds. Jezreel Valley in the Dark, whose making involved pouring black coffee into molds shaped as the fields of the Jezreel Valley, creates an agricultural landscape constructed from an organic act involving “seeding,” expectation, and time. Weinstein corresponds primarily with himself and with his monumental works The Valley of Jezreel (2002), Huleh Valley (2005), and Nahalal (2009-10), which introduced iconic images of Zionist agricultural settlement in the Land of Israel. The transition from substances such as felt carpets, linoleum, and steel wool, from which the previous works were made, to growing rugs of organic mold, transforms the artist himself into a farmer of sorts, and agriculture—into a grand, all too heroic image requiring darkening and domestication to become feasible. Weinstein does not attempt to obscure the Valley, but rather to discuss it as the residue of a monumental image, an incarnation of an artistic biography, and coffee stains. At the same time, the large coffee circles create a deep, dark cosmology which may be read as both earth and heaven at the same time.

Noa Raz Melamed created a moving “shadow theater” which rotates as a perpetuum mobile, hanging in the air, resting on hovering ridges. It is comprised of items from Petach Tikva’s historical archives combined with crumbs of biographical-familial memory. The installation Couch Grass blends the story of the Orthodox Jewish farmers who founded Petach Tikva, with the story of the Jezreel Valley pioneers, leaders of the secular, Socialist revolution, among them the artist’s grandparents (who met in 1917 in a workers’ kitchen in Petach Tikva). These two narratives—which are joined by a third narrative, about Palestinian citrus growing, unfolded in the animated film Fruit-Picking War—are woven around two key images: the root of the couch grass (injil in Arabic) and the orange: reddened like blood, the couch grass transforms into tendons (“To follow it as if you were following a tendon in the body,” poet Esther Raab, native of Petach Tikva, wrote about the injil); whereas the orange, tossed from hand to hand, becomes a symbolical object embodying these conflicted identities. Friezes of white plaster reliefs tie the evolving myth to ancient agrarian civilization, as a quote from Elazar Raab’s The Citrus Grove Diary—“With my own hands I pulled out the couch grass—hovers like a lost motto.

Raz Melamed’s shadow theater inquires about the gap between image and reflection and between reality and illusion. It touches upon the mythology of early agriculture and the beginnings of Zionism, as well as upon the apparatus of photography created from light projected on a surface. Amidst rocks and stones, animals and plows, the spectral silhouettes of A.D. Gordon, Yehoshua Stampfer, Jacob Raz-Rizik, and Sarah Raz-Rizik (the artist’s grandparents) also hover. In Fallow Year, the eponymous Hebrew word Shmita erupts from the chaotic realm of memory, projected in light on the wall. In 2015, a fallow year according to Jewish law, Raz Melamed proposes resignation, letting go of the passion for ownership and mastery.

In his life and art, Noam Rabinovitch maintains the routine of a farmer and hermit who sets off on his mission every morning. His work space is split in two: an unnamed wadi in the fields where he spends time, plants, hoes, and observes; and a studio space in which he translates his emotional and visual impressions into a set of actions, which also carry a repetitive and meditative nature: drawing on long scrolls, embroidery, piercing, or re-drawing on a single paper sheet (“running drawing”). These disparate acts are performed alone, without expropriating a space or drawing conclusions. Rabinovitch’s agricultural routine is foreign to collective notions such as “field,” “orchard,” and “territory,” yet acknowledges the “seedling,” “planter,” and “tree.” In his individual spirit and intimate proximity to nature and the land, Rabinovitch seems to realize A.D. Gordon’s vision: “We return to nature, neither as slaves, nor as masters, not even as tourists or scholars, […] but rather, as active partners and faithful brothers.”

Oded Hirsch’s films are centered on two major themes: an absurd attempt to challenge human capabilities and an implied reference to utopian pioneering projects. Hirsch creates artificial, planned situations, thereby modeling a bubble-like world, a type of “laboratory” which isolates and expands a single act, while charging it with visually and emotionally powerful, literally breathtaking, existential meaning.

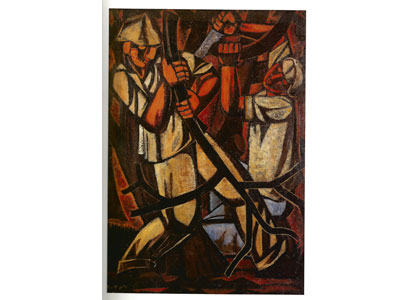

In his current film, which takes place in an unidentified mountainous site, Hirsch orders a group of elderly peasants to dig in the ground with simple tools they brought with them. Shot in black and white, the film’s expressive style corresponds with Soviet director Alexander Dovzhenko’s 1930 film Earth, unfolding the first encounter of peasants in the kolkhoz with agrarian technology in the form of a tractor. In Hirsch’s version, the old tractor is a type of fossil buried in the ground, and retrieved as a cultural icon. Despite the absence of geographic and national identification marks in the film, this confined drama and its protagonists allude to the declining mythology of Zionist agriculture and the era of legendary heroes who fostered it.

Ran Barlev’s Echoing Landscape fuses a representation of rural agricultural landscape with painted models of minimalist-geometric sculpture by Israeli sculptor Nahum Tevet: two utopian routes that outline the modernization of the local space (new Israeli agriculture) and the progressive paradigm of modernism (rational-geometric sculpture). A loudspeaker is planted at the heart of this “mixed” landscape, emitting sounds of cricket chirping and distant echoes of bass drums—a soundtrack of nature, night, and muffled tidings.

Bucket Conglomerates: buckets, sorted soils from the

Sharon (loam, loess, Nazaz, and sand), concrete, iron and

copper cables

Production: Renana Neuman

Assistants: Efrat Lipkin, Avi Ben-Shushan

The Hour “Control Cabinet”: 7-channel video

Camera and editing: Renana Neuman

2nd camera: Shira Tabachnik

Production assistant: Matan Oren

The House, the Soil, and the Grove: 3-channel sound

Interviewees: Yitzhak Gothilf, Eli Argaman, Abdallah Amash,

Oded Shellef, Nira Efroni

Interviewer: Relli De Vries

Interview editing: Gabriel Comidi

Soundtrack: Gustav Mahler, “The Farewell” from “The Song of the Earth”

(1908) performed by Kathleen Ferrier and the Vienna Philharmonic

Orchestra conducted by Bruno Walter (1952)

Sound arrangement: Assaf Talmudi

Digital LED strip

Text: Relli De Vries

Programming and control: Shmulik Twig

The installation The Book of Hours is constructed as an agro-mechanical apparatus which marks the poetic space of an agricultural universe. Inspired by The Book of Hours of the Duke de Berry painted in the 15th century, which depicts the orders of the world in terms of the cycles of the seasons and agriculture, Relli De Vries’s Book of Hours addresses Israeli agricultural time. It is informed by a link between biographical memory and theoretical knowledge, and between philosophical insight and political consciousness. The installation’s principal tension axis focuses on the polarity typical to Israeli agriculture: between the low, physical, gravitational aspect, and the fantastic, ideological ascending aspect. It is an electric tension axis which connects heaven and earth, and is stopped in the depths of the earth, like a ground; it ties the seven beams inserted in the museum’s ceiling, outlining the Big Dipper, to the bucket weights overflowing with soil placed on the ground. At the same time, it is also an axis of emotional tension, signifying the gaze which leads skyward, expressing the anxiety of uncertainty and the poetry innate to the farmer’s relations with the forces of nature determining his fate.

In the cluster of videos screened in the “control cabinet” dominating the installation, De Vries, the granddaughter of a farmer, one of the founders of Kfar Yona in the Sharon, marks three sites associated with the agricultural mythology of her family—the vacant and deserted farm house of “Mataei Hasharon” (The Sharon Plantations), the orchard cultivated by her father, and the orchard’s gate—through which she discusses site, ideology, and soil. “The Farewell” from Gustav Mahler’s cycle “The Song of the Earth” accompanies the photographic cycles which follow the setting of the sun and the waning of light. De Vries is interested in darkness as the time span when the earth leads its secret life for itself, with neither workers nor owners, guided by nature alone. “I look at the silent, exhausted land which was exploited as an ostensibly stable ground; I study it, and mainly contemplate it as a passive carrier of ideology,” she says.

The installation The Book of Hours engages with the Sharon, an area whose land has been deemed “collapsing land,” due to an extensive uprooting of orchards, and their transformation into real estate sites. The orange, the “Zionist diamond,” which was appropriated for the promotion of Zionism, and became its quintessential symbol, emerges in the genizah (archiving, shelving) cabinet standing on the right. There, it is presented once as “Earth”—a part of a cosmic scheme, alongside the sun (a grapefruit) and the moon (a lemon), and once again—as an empty peel. The yardsticks of the “Soil Erosion Station,” which was closed and liquidated, function as measures of an ideology which was excluded, eroded, and ultimately dissolved.

Thanks: Liron Alroy-Michaeli (Yoga), Adva Chalupovitch (dance), Noa Rosen, Yuval Erez, Keren Ben-Raphael, Ronen Nagel

(Sound Around), Racheli Ben-David, Shoshi Ciechanover,

the children‘s choir, the Ein Iron community

Agriculture: A Play in Five Acts begins with the curtain raising: the cloth and nylon sheets covering the greenhouse openings are rolled up, exposing the scene of action: the agricultural greenhouse. Ever since Avital Geva’s greenhouse was exhibited at the Venice Biennale (1993) and received a symbolic status as a space which connects agriculture with art and education, many growth cycles have passed. Sharon Glazberg’s “agricultural play” introduces a different type of greenhouse: it is a site populated by foreign Thai workers, on whose working hands today’s Israeli agriculture depends. Glazberg’s greenhouse, set up in the space of Petach Tikva Museum of Art, offers a backdrop for the drama of Israeli agriculture as a whole: from the foreign workers’ decorated farm-cart, which joins the traditional festive first-fruit procession in the moshav, to the watermelon scarecrows, dropping after being pelted by potatoes left in the field. The large leek flowers that have bloomed since the greens were not picked in season for lack of financial profitability, decorate the visages of the celebrating workers.

Glazberg intentionally avoids direct exposure of the workers’ living quarters or a disturbing specification of their rights. Instead of using them as a social protest poster to clean her conscience, she initiates and creates joint acts of fellowship in which some of the members of her moshav, her own children and their classmates, as well as the artist herself take part. “The play” is thus gradually devised; its protagonists are not only foreign workers, children, and moshav members, but also the spectacular field vistas, a pouring rain, pomegranate trees, and surrealistic images which open the agricultural setting to the experience of primal nature. Shavuot (Pentecost) procession—the ultimate ceremony of traditional Israeli agriculture—has assimilated the Thai workers, and transformed them into the new Zionists.

Courtesy of the artist and Chelouche Gallery for Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv

Supported by Outset.

Thanks: Prof. Avraham Levy, Prof. Yuval Eshed, and Yifat Tishler, Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot; Yivsam Azgad, spokesman and curator, Weizmann Institute of Science; Dr. Ilan Paran, Volcani Center, Agricultural Research Organization

The installation Mother of All Wheat was constructed as a cross between a greenhouse, a bunker for seed preservation, and a biological research lab; it simulates a vegetal gene pool which (metaphorically) preserves the “evolutionary intelligence” assimilated in the grain over millennia of agriculture. Tomer Sapir operates in an evolutionary range whose limits he himself sets, based on the architecture of the mother of wheat: an ancient, durable plant discovered in the area of Rosh Pina by agronomist Aaron Aaronsohn (1906), regarded as a genetic point of origin from which mutations crucial to the nutrition of Western man have developed. From this archetype Sapir generates artificial mutations, invents unknown configurations, mixes three-dimensional prints with manual work, and juxtaposes the organic source with synthetic details to create a broad spectrum of variations. As in Noah’s Ark, this “greenhouse-bunker” represents the genetic option for rebooting in case the old reservoir is destroyed or damaged irreversibly. He thereby indicates the dimension of risk and anxiety associated with agriculture, and its crucial significance to the future survival of mankind, whose uncontrolled reproduction poses a potential threat of starvation. Sapir’s installation, which focuses on one of the three major staples feeding mankind alongside corn and rice, discusses the traditional status of agriculture as “common knowledge,” which is at the disposal of the public, vis-à-vis current trends of technological intervention and genetic engineering.

“How does a man, a farmer, and this is significant,

all of a sudden detach himself from the element of rain?”

Dov Heller and Yaacov Chefetz’s joint project, North-South / Rainfall Region / Exchange, proposed to follow the amounts of rainfall throughout the country, from north to south, and translate the objective data into an internal reality based on their being farmers. The artists’ point of departure was their different places of residence: Chefetz then lived in Kibbutz Eilon near the Lebanese border, whereas Heller lived (and still lives) in Kibbutz Nirim in the Western Negev. The two likened the climate difference between north and south to the tension between a blessing and a curse, between drought and rain, and between security and tranquility, on the one hand, and anticipation and tension, on the other. To a large extent, Rainfall Region is also a map of the psychic fabrics of the inhabitants of north and south. It inquires: What is the difference between life in an area rife with water and precipitation and life in a barren area with little water? The regional rainfall map presented in the project proposes a geographical division which ignores political borders, and binds Israel and its neighbors together, and with them—also the farmers of these countries, in a similar psychic-agrarian state of mind.

For the project, Chefetz and Heller embarked on a two-person journey from Eilon to Nirim. They installed signs indicating the amounts of rain measured at different points along the route, built various rain gauges, and gathered data from the Meteorological Service. One of the high points of the project was an act of exchange between the two artists: Heller made a rain gauge in Eilon, while Chefetz erected an aqueduct in Nirim. The project also raises aesthetic questions pertaining to landscape conventions and the attempts by desert kibbutz members to grow a green landscape based on irrigation: “We have built a mini-environment for ourselves here which does not really belong to the place,” says Heller. “We came and raped. […] Who says loess expanses are not as beautiful as lawns?”

The project was presented at the Kibbutz Gallery, Tel Aviv (1979), the Jerusalem Artist’ House (1980), and Haifa Museum of Art (1981). The gauges, precipitation maps, journey reports, and two films juxtaposing the overflowing water in Eilon Stream with a flash flood in Nirim, were spread on the data table. Chefetz: “I belong to the physical state of the northern environment. There is a sense of contentment, expectations are met, summer, winter, the seasons and their fluctuations—all is expected and there are clear data about each season. […] A person sits at home up to 80 days due to rain; it is a physical condition which embeds a sense of permanence.” / Heller: “I have this graph: starting from around October I have expectations, […] I enter into a period of alertness. It is not just mere expectation, […] all year round I have an occupation, roulette. The issue of drought is the problem, not the technical solution [of irrigation…]. The disappointment is not only economic; it is an enterprise that belongs to you, to your soul.”

Courtesy of the artist and Rosenfeld Gallery,

Tel Aviv

Thanks: Yehudit Gottesman, Avraham Milgrom, Yael Frank, Katharina Kniep, Dudi’s Workshop,

Dani Carmi, Genadi Dubuskarski

A tall “totem” of a headless horseman, constructed as an axis between sunset and sunrise, dictates the structure of Zohar Gottesman’s sculpture/monument, introducing a scheme of transformation. Addressing the tension between the tradition of classical sculpture and contemporary, mundane materials, Gottesman’s work is based on the familiar image of the victorious horseman monument. His galloping rider sits backwards, holding the horse’s raised tail, exposing his anus. The marble and bronze—the noble materials of which such imperial victory monuments are made—have been replaced here with horse manure, a substance heaped behind the stables recently erected amidst the fields and orchards in the artist’s native moshav. The dung—malleable yet disconcerting material—is used due to its availability in the artist’s immediate surrounding and its being a marker of denial: it is ubiquitous, yet generally ignored, an expression of organic and economic “over fertilization” attesting to a change of priorities.

In the lower plane, under the horse’s hooves, is a lump of soil containing the archaeological remnants of a farm: parts of buildings, chicken bones, “Neolithic” masks made of orange peels, and various fossils, including a tractor carved in wood, carrying the entire Gottesman family, young and happy. The woodcarving is implied, alluding to Cubist geometry, an echo of an optimistic modernism cast into the abyss of history. Gottesman, the grandson of the moshav founders, raises questions vis-à-vis the new landscape, and observes a foreign culture, which boasts an unknown status. This entire array rolls on the transient basis of a horse trailer.