If I was Body

Curator: Irena Gordon

14/02/2025 -

21/06/2025

The exhibition If I was Body brings together artists who explore the fragility and incompleteness of the body in all its physical and psychological, human and nonhuman manifestations. It is a body currently immersed in an existential struggle, but its being is imbued with the memory and history of things. Despite its physicality,it is an abstract spirit and consciousness, a corpus of speech and thought embedded in matter.

An unbearable local reality simmers in the background of the exhibition, a reality in which the bodies of individuals and the civilian body as a collective are exposed to constant danger, enduring a state of emergency, ongoing war and trauma. At the same time, the exhibition is grounded in contemplation of the nothingness at the heart of the body as a concept—an intermediary between us and the world, transpiring along the continuum between the living-organic and the inanimate, mechanical, and virtual. In Israeli art, the body is never self-evident; it is always elusive, demanding a redefinition, partly due to the weight of religious and social perceptions.

In “Paradiso,” the third cantica of his masterpiece Divine Comedy (1308—1320), through the exclamation “If I was body” (S’io era corpo), Dante Alighieri expresses awe at the fact that his physical body ascends to the higher realms of Heaven, defying the laws of nature known on Earth. Dante delves into the magical nature of his journey, emphasizing the union between the human and the divine, while echoing Odysseus’s voyage through the mare magnum of existence as a metaphor for human fate intertwined with nature. He compares man’s relation to the divine with the relationship between the body of the self and other bodies—in this case, the planets—where the body is neither subject nor object. Closer to our time, in the mid-20th century, Jean-Paul Sartre argued that “nothingness lies coiled in the heart of being—like a worm,” suggesting that at the core of existence is a fundamental void, a nothingness, which undermines our sense of stability and meaning; whereas Jean-Luc Nancy claimed that the body is the site of existence, in all its physical, psychological, and mental aspects, and as such, it must be articulated repeatedly; one must touch it and be touched by it. Being as a body is always with other bodies, because it is only from the outside that the body can be articulated, between isolated subjectivity and a plurality of subjectivities.

The same is true of the manifestation of the body in the carnival, which Mikhail Bakhtin regards as an indication of the ambivalent or dualistic existential experience. The carnival is a participatory event in which the body is open to the world and relational, rather than closed within itself, blurring the boundaries between high and low and celebrating the affinity between womb and tomb. Claire Bishop also views the manifestations of the body in art as a participatory act, one that holds the potential for social transformation and the promotion of democratic values—even if at the expense of the visual image.

The participating artists create political and primeval, physical and emotional, autonomous and sensual bodies—occurrences, images, and objects that are pushed and pulled, hovering and breaking, while exploring the gaps between being and void, place and time.

Installation photographs: Tal Nisim

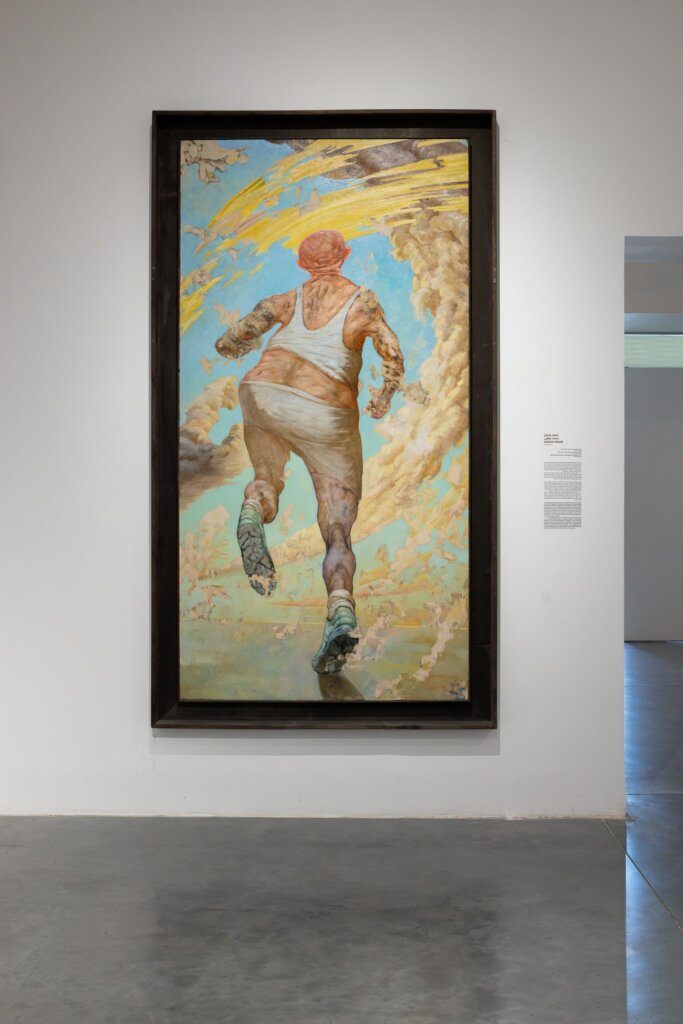

In his paintings and drawings, Sasha (Alexander) Okun seeks new plastic

and aesthetic regularity in continuation of the European figurative painting

tradition. He combines absurdity and pain, ugliness and beauty, realism

and surrealism, to create tragicomic worlds centered on the human body,

both singular and plural. In his paintings, the female and male bodies,

rooted in the existential solitude of everyday routine, become primordial

landscapes, and viewers are invited to contemplate the different

perceptions of reality that appear before them. Despite (or because of)

its transience, the body in Okun’s painting—which encapsulates time,

history, and space—is infinite.

In the painting featured in the exhibition, the professed sloppiness

of the grotesque figure negates accepted definitions of beauty and

aesthetics. The body is neither hidden nor disguised, and it is precisely

the presentation of things as they are that generates harmony with the

landscape in which it stands with its back to us, as a body gradually

turning into spirit. Matter becomes anti-matter, and the image seems to

hover, dissolving into the line and the stains of color, freeing itself from

mimetic representation and producing the sound of poetry.

Yakira Ament’s new body of work, created over the past year, emerged

from the drawing Mud and Smoke (2022), now joined by two Sprout

drawings, together forming a triptych of a primordial storm. Alongside

these she has created an array of two-part sculptures—totems of fertility

or spell casting/removal. The titles reflect the materials from which the

works were made—drawings and sculptures that resemble bodies in the

process of constant creation, before the separation of darkness and light,

earth and heavens. These fantastic, mysterious sculptures—hybrids of

nature and culture, beast and human—harbor explosive energies. In their

movement between figuration and abstraction, and between order and

chaos, they evoke the creatures populating Ferdinand Cheval’s Palais

Idéal (Ideal Palace), holding up a mirror to the anxious human soul.

Ament explores the physical-metaphysical transformation of form

and matter, tracing cyclical processes of renewal and deconstruction. The

works bear the imprints of the hands that created them, the processes of

their formation as bodies in progress, embodying a yearning for expansion

and continuity.

Adi Argov’s engagement with the body echoes her personal struggle with

physical limitations resulting from lupus, which she developed about a

decade ago. Her Sisyphean treatment of the physical and mental trauma,

in an attempt to relieve the pain and move freely, finds its way into her

drawings, which are also a tool for meditative, physical, and artistic

practice, similar to kinesics—the study of how body movements and

gestures are used in non-verbal communication.

Argov draws with acrylic pens on Kozo paper, based on a method she

developed that combines various signs with line drawings of body parts,

skeletons, joints, and figures, either human-figurative or hybrid. Within

the drawings, she writes in a code language she invented, incorporating

elements from Braille and movement scripts such as Eshkol-Wachman

movement notation, Rudolf Laban’s movement analysis, experimental

music scores, medieval choreography diagrams, and ancient maps. The

various signs lose their original meaning and become clusters of actions,

while the repetition generates a lexicon of images and shapes in layers of

drawing. In the animated works, the drawings transform into breathing

bodies, living systems.

Berlin-based Rimma Arslanov’s paintings unveil playful circus-like, yet

melancholic compositions, dreamy worlds that shimmer like visions or

hide behind curtains. The series of paintings shown here evolved during

the war. It began with drawings made as part of an artist’s residency at

Artport, and was completed especially for the exhibition, expressing a

sense of the body’s disintegration, a continuous disdain for physical and

psychological existence to the point of peeling off its skin. What remains

are surrealistic amorphous masses bearing memories of the past in

the form of earrings, fingerprints, or the roof of a house. The dissolving

portraits convey an elusive fragility, as the cold, blue-purple hues are

associated with the body’s interior—alive and breathing, but also bleeding

and transmitting coldness, repression, and distance.

Doris Arkin creates sculptures and installations through an ongoing

laborious manual process of cutting and joining, piercing and connecting,

in materials such as iron and bronze, fabric, paper, wax, threads, scrap

metal, and personal objects. From all of these, she assembles grids and

weaves, which in turn spawn three-dimensional bodies, structures that

record personal and collective memory as vestiges of an absent presence.

The work Matter alludes to the material of creation and the

universe, while also encapsulating the word “mother” (mater, in Latin).

It is a sculpture resembling a well or a basket from which a cloth of sorts

flows. Both are made of metal, emerging like primordial matter, with the

metallic textile seemingly stretching and spilling outwards. The oozing

mass carries memories and emotions of the vulnerable body, of which

only traces remain as soft-looking remnants despite their actual rigidity.

The work was first exhibited at the Beit Uri and Rami Nehostan Museum,

Kibbutz Ashdot Yaakov Meuchad.

An integral part of Arkin’s sculptural work is a private collection of

fertility and maternal figurines. The collection, assembled over more than

15 years from various sources, includes figurines from the Middle and Far

East, Europe, Africa, and America, which represent diverse and distinct

aspects of motherhood in ancient and tribal cultures. The physicalemotional

expression of the figurines in the collection is interwoven in

Matter, forming a timeless artistic dialogue that introduces a space for

reflection on the nature of human bonding.

The body is a central player in Yasmin Davis’s video works, but its

boundaries are constantly challenged as an elusive image between the

illusory and the corporeal. In Rustle, the body as a substance or trace

flickers in minute, almost imperceptible occurrences.

The artist’s body is examined in relation to the viewer and the

barrier between interior and exterior, as a separating layer that protects

the house from the outside world. The hands affirm the existence of

the partitioning, and at the same time—the closeness between mother

and daughter in the inevitable process of separation occurring as one

body transitions into two autonomous ones. The filming of Rustle, which

debuted at the Artists Residence Herzliya, began shortly after the birth

of Davis’s daughter and continued for three years, exploring the trinity of

reality, image, and language. As in Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, external

reality is reflected as an image through the mediation of shadows on the

curtains of the house, and the artist conveys that reality to her daughter

using the language she is learning to recognize.

Muhammad Toukhy explores themes pertaining to place and belonging,

home and protection, reflecting the Palestinian cultural heritage. Born

and raised in Jaffa to a family deeply rooted in the city for generations,

he regards the body and space as a physical infrastructure that bears

political meanings. His works reveal the process of the body becoming

a “structure” for others to read and interpret, in a visual language that

seeks to deconstruct its baggage.

Toukhy reimagines designs and ornaments in which he finds spatial

potential, viewing them as an object that has the power to expand and

spread by virtue of its infinitely repeated pattern. His work emerges from

“structures that may resemble a carpet, a mattress, even a tomb, but he

constructs them in digital spaces that have no direct physical existence,”

as he attests. In the next sculpting phase, he uses materials from the

worlds of construction, computer processing technologies (CNC), and

3D printing. In doing so, he allows the body and the space to redefine

themselves and their interrelations.

Nirit Takele’s paintings are centered on massive, monumental sculptural

human figures. At times they depict a single figure, but more often they

feature social-communal ensembles. Another striking feature is the

vivid coloration in shades of red, blue, orange, and brown, which took

root in her paintings after a sojourn in Ethiopia in 2017, during which

she became closely acquainted with the local culture of her country

of origin, the colorful clothing, and the landscapes. The bodies of the

Jewish-Israeli woman and man of Ethiopian descent in her paintings carry

a soft, heroic power of friendship and attention. Inspired by modernist

muralist painting, Takele conveys the resilience of the Ethiopian Jewish

community (Beta Israel), while also addressing themes pertaining to

identity and immigration in general.

In the painting The Glass Mantra You Wanted Me to Adopt, Takele

challenges the inherent biases against immigrants and newcommers, while

also highlighting the discrimination faced by other social minorities, such

as gender or ethnic groups—framing their achievements as examples of

those who “broke the glass ceiling.” This is symbolically represented by

a transparent, almost invisible strip, outlined above the dynamic mass of

men in the painting. In the New Body Part paintings, created especially

for the exhibition, Takele touches on the wounded, amputated, gilded

body as if it were a precious jewel.

The point of departure for Avital Cnaani’s works is her own body. Its

abstraction serves her to create sculptural bodies from such materials

as wood and paper. In the exhibition, she installs a new spatial array

of wood and paper sculptures that conduct a dialogue—narrow bodies,

bent like stems or branches, topped by large aquatint etchings bathed in

a bright, sensual and dreamy blue. The large-scale etchings hang in the

air, themselves forming three-dimensional bodies, carrying the memory

of the plates from which they were printed and hand-cut in an almost

sculptural manner. Cnaani likens the paper to a body that bends, sprawls

and stretches, like a garment, folded in a wardrobe that remembers

the body; like a map that conceals depth and distance, land, water and

horizon. The branches and stems also seem to bend and bow their heads.

Cnaani’s work converses with modernist sculpture in Israeli art—

the masculine sculpture in iron and bronze—and even with the work of

her grandfather, Yehiel Shemi, who pioneered abstract sculpture and

sought movement and softness in metals. Cnaani, in turn, introduces

a dialogue with nature and the human body through a choreography of

movement in matter—in her case, the paper or wood; while exploring

the essence of the stain and the line, she strives for the material’s most

ethereal dimensions.

Ofer Lellouche explores universal elements in the manifestations of the

world. His figurative-looking imagery is, in fact, a product of reduction,

seeking the essence of things in the space between representation of

reality and formal refinement. In this ongoing journey of deciphering, he

creates multiple versions—in sculpture, painting, drawing, and print—

addressing recurring themes: still life, landscape, and most notably the

human figure. Even in self-portraits, Lellouche’s figures are devoid of

identifiable personality traits, imbuing the works with a quality that is

both archaic and futuristic, immortal and enigmatic in its anonymity.

Comprising five sculptures created by Lellouche for a

comprehensive exhibition in China—Male Head, Seated Man, Standing

Woman, Pregnant Woman, and Female Head—the monumental sculptural

suite Atelier, After Courbet is now being shown in Israel as an ensemble for

the first time. Observation of random groupings of sculptures kept on the

studio shelves yielded a cluster of sculptures which together form a hand.

This group may be described as a collection of “corporeal entities”—whole

or partially severed, female and male—that maintain formal and abstract,

physical and psychological affinities. In their existential solitude, they

support each other. The cluster of works is a tribute to Gustave Courbet’s

realistic-allegorical 1855 painting, The Painter’s Studio, expressing

reflection on the work of art and its affect in the world.

Installation photograph: David Frenkel

From the outset of her artistic career in the 1990s, Hila Lulu Lin Farah

Kufer Birim has created a unique, distinctive, groundbreaking language,

centered on her own body and on objects that she deconstructs and

reconstructs to defy definitions and challenge fixed perceptions of

passion, beauty, and protest. Her works in diverse media—video, sculpture,

drawing, artist’s books, concrete poetry—introduce cyborg hybrids that

spawn a differentiated aesthetics, surrendering pain and discontent,

disruption and gender fluidity. Her oeuvre at large is a fantastic-allegorical

network, proposing exceptional, critical and scathing associations

between the politics of the most private, autobiographical and bleeding,

and that of the collective and of conflictual symbols and values.

The two video works featured in the exhibition, both from the turn

of the 20th century and the early 2000s, connect the seductive body,

exposed in its fragility, with another element, both artificial and organic:

a flower that she constructs and deconstructs, and then reconstructs

against her bare thighs, or a heart of frozen milk gradually melting between

her thighs. The images are mesmerizing in their persistence, tenacious

in their poetics of outcry.

In her oeuvre from the mid-1990s to the present, Sigalit Landau has

examined the imprints of the past and history on contemporary Israeli

reality. Quintessential characteristics of the local social, cultural, and

scenic space transform into expressive allegories, iconic in their power,

centered on the body. Natural and manmade habitats converge in bodies

that are compressed in excess and congestion.

The sculpture Rock-a-Bye Baby (Comfort Zone as per the Hebrew

title), debuting here, continues a chapter from a series of sculptures

created by Landau in 2013 for her exhibition at the Negev Museum of Art.

The series engages with maternity, while conversing with iconographic

images from the history of art, such as the Madonna and Child, or the

sculpture presented here—a marble nursing pillow, which resembles a

soft and flexible transitional object. The object’s lines are delicate, like

those of natural forms, conveying a sense that is antithetical to the hard

material from which it is made. The transformation of the maternal bond

from a human body to a body-object, in addition to the ironic title, results

in playfulness mixed with pain in its reference to the physical-mental

bond and its reflection in sculpture as expressive means.

Maya Muchawsky Parnas presents a repetitive array of sculptural bodies—

oval frames containing parts of relief-like images of nature and still life

representations: plants and animals, figures and objects, extracted from

classical paintings reproduced on decorative vessels. These segments

are arranged in a vertical row of fragmented forms, creating a stratified

system that invites a peek inside. The internal vortex of broken forms and

torn images reflects a scattered, vague thought, in which the fragments

of the 2024 reality try to coalesce into a coherent image.

The work is made of porcelain pressed into a mold, which, due to

its material thinness, barely holds together and is constantly tearing and

collapsing. Only what survives is fired and fixed. The thinness lends the

material transparency, contributing to the fusion and soft transitions

between layers. Light also passes through the layers of material,

generating dreamlike moments. The seriality—a hallmark of Muchawsky

Parnas’ work as a whole—creates a duration of material, observation, and

practical knowledge.

Merav Maroody, who also works as a film and fashion photographer,

created the series Plastic Animals in an attempt to capture the sense of

physical void and distance in her existence as an immigrant currently

living in Berlin, in constant search of an alternative family. Following a

series of traumatic events that necessitated a process of recovery, she

joined a group of friends on a trip to Poland, where she documented the

participants wearing plastic animal masks. The friends, all immigrants

themselves, transformed into a group of hybrid bodies that integrate

into and reflected in the scenery, feeling comfortable behind the masks.

The new family created by Maroody through the masks unfolds

a new mythology of belonging and alienation, since the mask, whose

expression is either emotionless or exaggerated, conceals both danger and

opportunity, like the carnival mask. The photographs in this alternative

family album are not rooted in the domestic space but in nature,

enhancing the experience of alienation. Against fixed perceptions of

the beastly-human binary opposition, Maroody explores the “point of

transformation from victim to monster,” from empathy to aggression.

Multidisciplinary artist Vera Korman explores the interface between

personal and collective memory through the body as a locus of disciplining

and seduction. Omri Alloro’s works examine architectural manifestations

that relate to human interaction, creating interactive spaces that invite

the viewer to take part in the work.

The body of the sculpture, created by Korman and Alloro especially

for the exhibition, is deconstructed as on an assembly line, incorporating

a vibration of synchronized lighting and sound. It is a hybrid body made

of flexible silicone, with a texture somewhere between bare flesh and

clotted jelly. At its center is the smoothie—a programmed mixer of lights,

movement, and sound. The body parts are arranged like exhibits in a

science museum, as if engaging in a symposium of a deconstructed body

with and about itself, in philosophical, psychological, and scientific texts

and sound that processes a New Age meditative discourse of relaxation

and therapy. The complete audiovisual sculpture, with its vibrating

textures and flickering lights, is a deceptive theatrical performance

of fictive triggers—a digital sensual space of artificial desire, blending

an intimate experience of partnership with a sense of terror, anxiety,

and confinement.

Addressing questions of identity and memory and the connection between

man and landscape, Alex Kremer’s paintings are characterized by powerful

expressiveness, vivid colors, and accentuated, dynamic drawing lines,

which enhance the works with the illusion of depth and movement. In

figurative compositions verging on abstraction, the paintings convey

intimacy and solitude. Change is a condition for life, and the images are

in constant transformation of everything human and natural.

Kremer created the works on view about a decade ago, in a drawing

movement of a thin line that spawns an elegiac human figure. One of

the paintings portrays the artist drawing a skull—a typical image that

represents life’s transience in Memento mori (“remember you must die”)

paintings. The poetic inscription Anatomy of the Heart, hangs above it,

capturing the ephemerality and fragility of the soul, the body, and the

work of art.

The series of photographs Impression (Rodin Museum) was created using

a unique technique developed by Yana Rotner working with a 16mm film

camera, extracting individual frames from raw material she filmed and

printing them on paper. In this practice, Rotner proposes a different

observation of what memory did not have time to record.

The contemporary photographer’s gaze thus initiates a dialogue

between the process introduced by the Impressionists in the mid-19th

century, in an attempt to capture the fleeting moment, and the significant

impact of photographic innovations on the development of painting; and

between these and the groundbreaking work of Auguste Rodin, whose

sculptures explore the movement of the human body and its expression,

as a whole and as a fragment. The gaze in her works is both a pause and

a variation on observation, on the perception of the human.

Multidisciplinary artist Yuval Shaul combines traditional and industrial

materials with readymades to construct spectacular hybrids. A central

motif in his work, which blends the organic and the artificial, is a hybrid

human-beast. His self-portrait frequently appears in his works, which

explore themes of masculinity, power, violence, and compassion. The

sculpture on view was originally a realistic sculpture created with a 3D

printer: a life-sized image of the artist carrying a duplicated image of

himself—a wounded figure, or one requiring support. In the exhibition, the

sculpture is presented in a deconstructed version, its parts scattered on

the floor as relics of past splendor or pretentious perfection, reminiscent

of the fragments of the monumental statue of Emperor Constantine in

Rome. It may have collapsed, no longer able to support itself.

Yoav Shavit’s installation Infrastructure Problems originated in a

malfunction in a construction site—the moment of a pipe explosion which

was frozen in time, with the shape of the objects representing their mode

of formation. A primal form that burst from a pipe as a result of heat and

pressure becomes a “pregnant” mold that envelops another, which in turn

emerges therefrom, and so on. The results are biomechanical creatures,

amusing and even absurd to a certain extent, which oscillate between

figuration and abstraction in a quasi-ritual space on a bed of quarry sand

used in building sites.

The interrelations between the fragments of chaotic formations,

in the pursuit of precision and aesthetic satisfaction in the complete

product, are revealed as a destructive struggle. The artist’s voice emanates

from one of the sculptures, posing— in what sounds like a prayer, a

lamentation, or perhaps a chant— one of the fundamental philosophical

questions introduced by philosopher Emmanuel Kant: “What am I

allowed to hope for?” The sound work infuses an apocalyptic atmosphere

with sober observation. The aestheticization of magical forces spins

a contemporary, secular cult from a cluster of organic, synthetic, and

technological materials.

In his extensive oeuvre, which has left a lasting mark on Israeli art, Igael

Tumarkin incorporated the influences of Dada and Pop Art in sculptural

and assemblage techniques that combine ironwork and readymades.

His expressive formal language has consistently conveyed a fierce,

biting protest, engaging in constant dialogue with both local and

European culture and politics. Tumarkin created dozens of sculptures

and monuments installed throughout Israel, alongside prolific work in

painting, drawing, and printmaking, theater set design, personal and

theoretical writing.

For Tumarkin, the body is a battlefield, bringing together the

conflicts and myths of Western history and Israeli reality. Through the

human-sculptural body, he explores the imprints left by time on the

concepts of art, culture, and identity, navigating the space between

paganism and capitalism. In the works presented in the exhibition, the

heads of Renaissance artists and architects Filippo Brunelleschi and

Michelangelo Buonarroti are cast in iron, seemingly impaled on high

pedestals, like medieval machines made from folded metal vessels, from

which obscure implements—either instruments of torture or eternal

totems—are suspended.