Lali Fruheling: Dawn

Curator: David Frenkel

21/06/2024 -

11/01/2025

In the exhibition Dawn, Lali Fruheling (b. 1982) performs a laborious mourning ritual of sorts, starring the remains of a collapsed life in two adjacent spaces. Fruheling’s works are seductive and dazzling, prancing around morbid kitsch and unresolved violence as if they were enchanted. It is pop, sparkling with excessive sweetness, a romantic theater over which she sprinkles dark flakes of dream. Sensual beauty, grace, pain, and horror are inextricably intertwined.

The installation is revealed from the corridor and we are invited

to peek in, to a crowded, intimate children’s room. On a pedestal rests

a man’s arm with a rolled-up sleeve, exposing strands of male hair,

together with a compact, festive array of colorful children’s tattoos,

made to fade shortly after being applied. Next to it, on the carpet, is a

self-portrait of sorts in still life format, cast by the artist in her hyper-realistic style. Another incarnation of the failure of love awaits us in the

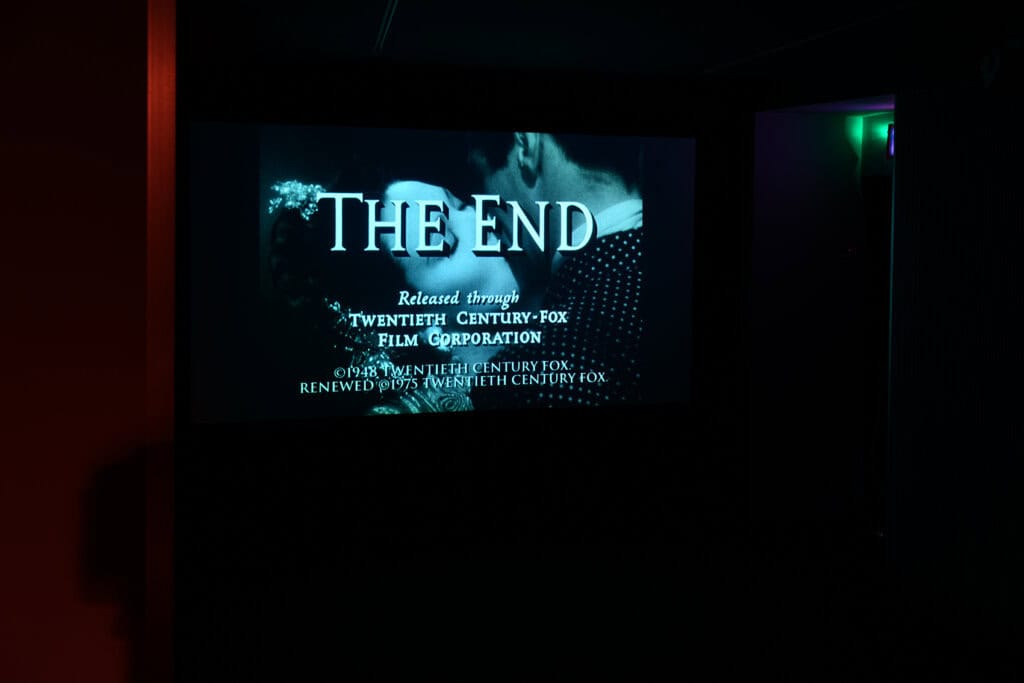

screening room. Romance will fade despite the Hollywood promise

for a dawn of a new day.

Fruheling’s practice is based on a long tradition of wax sculptures

used in religious worship, in science, as well as in spectacular

cabinets of curiosities. French thinker Maurice Blanchot remarked

on the connection between the nature of the image and the corpse:

“The image does not, at first glance, resemble the corpse, but the

cadaver’s strangeness is perhaps also that of the image. What we

call mortal remains escapes common categories. Something is there

before us which is not really the living person, nor is it any reality at

all. It is neither the same as the person who was alive, nor is it another

person, nor is it anything else.”*

The room’s ceiling is covered by a disassembled cardboard

piñata, with colored strips of paper dangling from it. It unfolds like a

spreading mushroom, already broken open to extract its assortment

of party gifts. The dissonant tension embedded in the piñata can

be seen as the engine underlying Fruheling’s exhibition. The piñata

encapsulates, in an innocent, festive envelope, both the latent objects

of desire and the instinctive, violent impulses seeking cathartic outlet.

The object, which is used in religious celebrations and other parties,

comes in a variety of forms and boasts numerous origins. In one of

its Catholic versions, for example, the piñata represents evil, and the

“blind” worshipper fights the deadly sins and Satan’s temptations with

his eyes blindfolded. And lo, here, in Fruheling’s work, the piñata has

swollen to room dimensions, and it seems that we, too, are invited

to join the destructive binge, to stretch out our hand and knock down

the walls of the house.

* Maurice Blanchot, The Space of Literature, trans. Ann Smock (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1982), p. 256.

Installation photographs: David Frenkel