Last Chance to See

Curators: Drorit Gur Arie, Isabelle Bourgeois

08/11/2018 -

16/02/2019

“Last Chance to See,” declared British author Douglas Adams in his amusing travel book, which gave its title to the exhibition. Adams teamed up with zoologist Mark Carwardine, embarking on a journey in search of the strangest and most endangered species of animals on the planet. The title emphasizes the quest’s urgency, indicating the desire for a physical encounter with the object of the search and the aspiration to study it through the body, in the flesh.

The exhibition addresses the various routes and repercussions of human mobility in the geographical, physical, and linguistic spheres, as experienced, signified, and processed by contemporary artists from Israel and France—countries through which two of the most important Christian pilgrimage routes since medieval times pass: the route to Jerusalem and the route to Santiago de Compostela. The geographic settings in which the artists work are thus infused with the traces of past pilgrims, who left their imprint on the local landscapes and cultures.

Unlike traditional pilgrimages, the pilgrimage routes outlined here are not centered on arrival at the longed for destination, but rather on the movement itself as a near-sublime act which is performed for its own sake; they introduce the journey as a repetitious motion, possibly meditative, which in some instances even causes damage to the physical body. At the same time, this movement echoes contemporary life styles, which are rife with transitions and trespassing of territorial borders, as more and more people cover distances and lead a nomadic way of life, whether real or virtual.

In his travelogue America, French philosopher Jean Baudrillard describes movement in a desert-like space, devoid of reference points, which concludes with realization of the journey’s endlessness. In the journeys featured in the exhibition, the artists set out to re-map systems of knowledge and language, human contacts and optional resources. The resulting alternative cartographies function as infrastructure for new excursions of searching, gathering, and documentation, which are translated into poetic forms of data processing and spatial navigation.

Courtesy Galerie Sultana, Paris

The recordings for this sound installation were made in collaboration with Israeli surfing clubs. The artists use the jumble of languages and the voices of surfers in Tel Aviv, both locals and tourists, to map the local human landscape, not necessarily in typical friction spots which represent the tensions of life in Israel, but rather in the territory of this popular sport, associated with freedom and tranquility. Recording sensors were also attached to the surfboards, capturing the sound of the waves and the noises made by the boards as they cut the water. These sounds, alongside the casual conversation about surfing and its meaning, spawn a sound piece which fuses the chaotic and the harmonious in an unmediated encounter of movements and interactions, surfboards and people.

With the support of Outset and Erel Margalit

In Butterflies, Orit Raff embarks on a journey along the Burma Road—the bypass route over which supplies were transported to the then besieged Jerusalem during the War of Independence. She physically traces the driving route used by the armored convoys between Latrun and Jerusalem, holding a bouquet of balloons shaped like “butterfly” armored cars, whose nickname derives from the ventilation apertures in the roof reminiscent of butterfly wings.

In a nearly childish gesture, performed over an exhausting 15-km hike, Raff releases the balloons one by one, like disappearing tracks or futile road signs. As opposed to the heavily armored steel car skeletons, which were left on the roadside to commemorate the difficulties along the way, the armored-car balloons soar high lightly and airily. The irony, innate to the chosen name “butterflies” for those crude, heavy vehicles, is reinforced through the juxtaposition of the military aesthetics of the armored car with the release of the balloons associated with the childhood world.

The balloon release, while climbing uphill toward the Holy City, conceals the sacred and the profane, effort and determination, hope and despair. Raff’s march calls the pilgrims of the past to mind; those who embarked on a heroic journey, which involved numerous dangers and hardships, to fulfill a religious commandment. In Butterflies, the focal point is not the sacred destination and arrival thereto, but rather the process and the physical journey, which consists entirely of an intense monotonous act. As in Raff’s previous works, this ostensibly futile Sisyphean act demands determination and devotion, characteristic of a naïve world view.

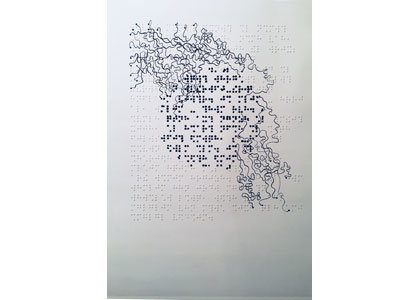

Dafna Shalom presents works from the series Night Writings, painted on sheets of Braille text used by the blind as a method of reading, employing the sense of touch. The painting on Braille was intended to extract the physical dimension from language. Braille serves here as a metaphor for orientation and otherness, as it creates a sensory, three-dimensional space for people living on the margins of society.

Shalom chose to work with H.N. Bialik’s 1915 essay “Revealment and Concealment in Language” and Roy Hassan’s 2013 poem “From the Inside.” The former discusses the historical quality of language, the changing meaning of words which are not fixed or eternal. Words and language, Bialik maintains, conceal reality: “…every speech, every pulsation of speech, partakes of the nature of a concealment of nothingness […]. No word contains the complete dissolution of any question. What does it contain? The question’s concealment.”* Hassan’s poem links the erasure of language with the erasure of culture, so that it is precisely the removal of the linguistic “concealment” via the act of erasure that leads to concealment of the culture associated with it. In the work centered on this poem, Shalom erases parts of the text with brush strokes, accentuating the erasure gestures with paint.

These works are akin to abstract maps which generate a mental journey between the dots scattered on them, but it is hard to pinpoint Shalom’s point of departure and end point on the textual surface. Her act infiltrates the realms of consciousness, calling for re-orientation in their obscurities.

* H.N. Bialik, “Revealment and Concealment in Language” (1915), trans. Jacob Sloan, in Modern Hebrew Literature, Robert Alter (ed.) (Springfield, NJ: Behrman House, 1975), p. 132.

A mental-geographic journey in a studio-boat turns its gaze at what is going on in the mind of the sailor-artist through representations of his surroundings, or the objects around him and the thoughts in his head. One image follows another to produce a continuous shot which imitates an ongoing, uninterrupted ride, yet appears as a combination of different experiences without a connecting thread. Jean-Baptiste Warluzel draws parallels between the editing technique and the near-mechanical fragmentation of thought. He employs the painter’s and sculptor’s tools to melt materials from other media, such as music, cinema, and television, to create a poetic collage centered on the work processes. The different chapters are orchestrated into a symphony of text and image, which the artist conducts, while expressing his views on art and life.

Leor Grady’s Gold Boat is based on a mapping of the artist’s personal space on a 1:1 scale. In its first version, featured in New York in 2010, the artist covered his bedroom floor with paper sheets attached to one another and folded to form a giant paper boat. Translating the bedroom into a paper boat by means of the Origami tradition gives the boat a childlike quality, like a map of dreams. Its gold color, which corresponds with previous works by Grady, places the dreams between the realistic and the yearned for, the mundane and the sublime. Much like a real map, which translates data about a place into a visual representation, this map, too, signifies a concrete space. Unlike a map, however, it represents a place without a legend or an index on which to rely. The personal space thus remains a secret; a riddle undecipherable to anyone other than the artist himself.

In different languages, the consonants and syllables are voiced based on their place of articulation in the mouth, as a space which resembles a sound map. The sounds produced in the mouth in Marie Chéne’s work blend words and expressions in Hebrew, English, Arabic, and French, played via a mechanical music box apparatus. The expressions were selected based on meetings and dialogues conducted by the artist with various writers, linguists, artists, and intellectuals who work with language and use it as a pivotal part of their practice. Like her earlier works, which also addressed the different meanings of language and the diverse meanings and contexts often embodied in a single word, the current work, too, strives to challenge the exegetic boundaries of words, and to consider them in terms of sound, form, and body, closeness to or distance from the origin of language, while also contemplating the additional layers with which they are charged during the translation journey.

The Israel Trail: Procession is a large-scale joint project by artists Meirav Heiman and Ayelet Carmi, depicting a group journey along the National Israel Trail. The procession of hikers along the trail—a hiking route that runs the length of the State of Israel—extends over three of the walls. The identity of the participants—possibly nomads, possibly survivors or refugees—is unclear, since they carry no markers of affiliation or time. They advance using odd devices which prevent their feet from touching the ground, generating a peculiar, alienating movement experience between the hiker and the land. Walking becomes a strenuous acrobatic choreography alluding to either circus processions or pilgrimages wearing torture apparatuses to test their faith.

The project explores the charged relationship with the land through the contemporary rite of passage of walking the National Israel Trail, a quest deeply rooted in the Zionist ethos of conquering the land by foot. The morbid-ritual procession only externalizes the unstable, elusive, extremist dimension of the ritual. The journey, which involves great physical effort, conjures up masculine and military initiation rites of physical and mental stamina. Here, however, the convoy consists mainly of differently-aged women who resemble priestesses or warriors taking part in a protest march.

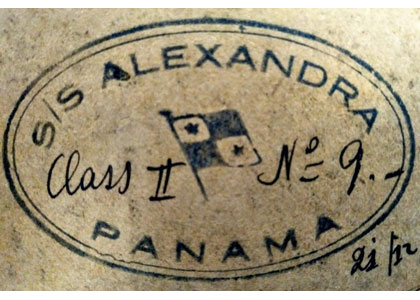

The video piece Very High Frequency is an introduction to new research conducted as part of the Ex-Territory project on which Maayan Amir and Ruti Sela began work in 2009. The project stemmed from their interest in the maritime ex-territory which is not controlled by nation states, and addresses additional aspects of ex-territoriality in local and global contexts. The current video work likewise explores the maritime ex-territory, in continuation of the artists’ study of a unique phenomenon, the use of “flags of convenience”—an ex-territorial practice which enables registration of watercraft under the flags of extremely poor countries as a way to skirt the law and avoid basic respect of human rights and the environment. The scope of the phenomenon is massive. Thus, for example, the use of Panama’s flags of convenience—a small country numbering approximately three million people—has transformed it into the owner of the largest fleet in the world, larger than those of both the USA and China.

While the use of flags of convenience is fertile ground to avoid civic duties or paying taxes, and for violation of safety regulations and human rights, Amir and Sela’s research is interested in the more humane contexts of the phenomenon, such as aid to refugees. The project delves into the affinities between the history of the use of convenience flags and the practice of asylum seeking, exploring the ways in which the boundaries of moral obligation are shaped in relation to the creation of such comfort zones.

אף שהשימוש ב”דגלי נוחוּת” הוא כר פורה להתחמקות מחובות אזרחיות או תשלום מסים ולהפרת תקנות בטיחות וזכויות אדם, מחקרן של אמיר וסלע מתעניין בהקשרים ההומניים יותר של התופעה, למשל בשירותם של פליטים. הפרויקט מתווה את הקשר בין ההיסטוריה של השימוש בדגלי נוחות לבין הפרקטיקה של בקשת מקלט, ובוחן את דרכי העיצוב של גבולות המחויבות המוסרית בזיקה ליצירתם של אזורי נוחוּת מעין אלה.

Extending over eight television screens, this video installation follows the ongoing, monotonous movement of a swimmer cruising between the screens from above. His figure is revealed on a different screen each time, leaving behind a coiling trail of blood which marks the movement path and slowly dissolves in the blue water. In cinematic thrillers, a trail of blood usually indicates an imminent tragedy, but here the swimming carries on undisturbed by virtue of the loop device.

Like other works in the exhibition, Bercovier’s work, too, engages with movement as such, movement which is not intended for any destination. It is based on the Greek myth of Hero and Leander’s tragic love, recounting the story of Leander, who swims across the strait every night to meet his beloved, but drowns one stormy night when the lamp lit by Hero to guide his way, is blown out by the wind. Here too, despite the struggle against the elements, the swimmer does not reach his destination. Like Sisyphus who never fulfills his task, he remains trapped between the screens in endless movement.

A horse with a camera on its back stands in the middle of the city, in an unused “dead area.” The “horse camera” scans its surroundings concurrent with four other cameras, which add information about the occurrences from different angles, enhancing the study of the given area. The horse functions as a mediator between the people and the “dead spot.” Pascal Simonet’s experiment draws the attention nearby residents, heightening their alertness to the occurrences taking place under their windows. The work as a whole raises questions about environmental planning, urbanism, and the implications of growing urbanization. It also addresses the interrelations between human beings, between people and their residential settings, and between the city and the animal.

Artists Romain Rondet and Gabriele Salvia come from different disciplines: cinema and architecture. As an artist duo, they explore the notions of psycho-geography, which delves into the influences of the geographical setting on the shaping of consciousness, mindsets and culture, into power fields and currents of passion concealed in city streets, projecting on the behavior of individuals and groups. Since the abstract mental space projects on the actual field of action, any intentional influence on it, regardless of how minor, is construed as intervention in human existence, which entails a chain reaction of reciprocal actions.

Rondet and Salvia’s work was inspired by Robert Kramer’s film Route One / USA (1989), which documents his rediscovery of the US while driving down the East Coast. Rondet and Salvia are also interested in the changing landscape and the appearance of the periphery, but their study focuses on different routes, in the vicinity of Jerusalem (Route 1, Route 443, Hebron Road). The camera captures the sights through a bus window and the landscape’s generic shell, slowly removing the layers of history and political tensions. The vistas are accompanied by background narration, which reveals the artists’ thoughts during the journey.